News

The Jackie Robinson Museum Is About a Lot More Than Baseball

Robinson accomplished a great deal on the field, but a museum celebrating his life puts as much focus on his civil rights work.

READ MOREPlan your visit or become a member today! Get your tickets for January Programs & Events!

In the early 1960s, both Jackie Robinson and Malcolm X were towering figures in the struggle for racial justice in the United States. Though they were both active in Harlem during a time of tumult and political upheaval, they drew their support from different constituencies and often had sharply contrasting views on how the unfolding movement(s) should proceed. Though they met in person only briefly in 1962, they traded barbs and disagreements in newspaper columns, debating the stakes of the movement openly and in public. Robinson accused Malcolm of attention-seeking and poor leadership, while Malcolm criticized Robinson’s associations with white moderates who were often unresponsive or hostile to the demands of Black communities in cities across the country. Even so, the two were more aligned than either readily admitted. After Malcolm’s assassination in early 1965, Jackie wrote that the pair largely agreed on the severity of the issues facing Black Americans, even if their tactics diverged.

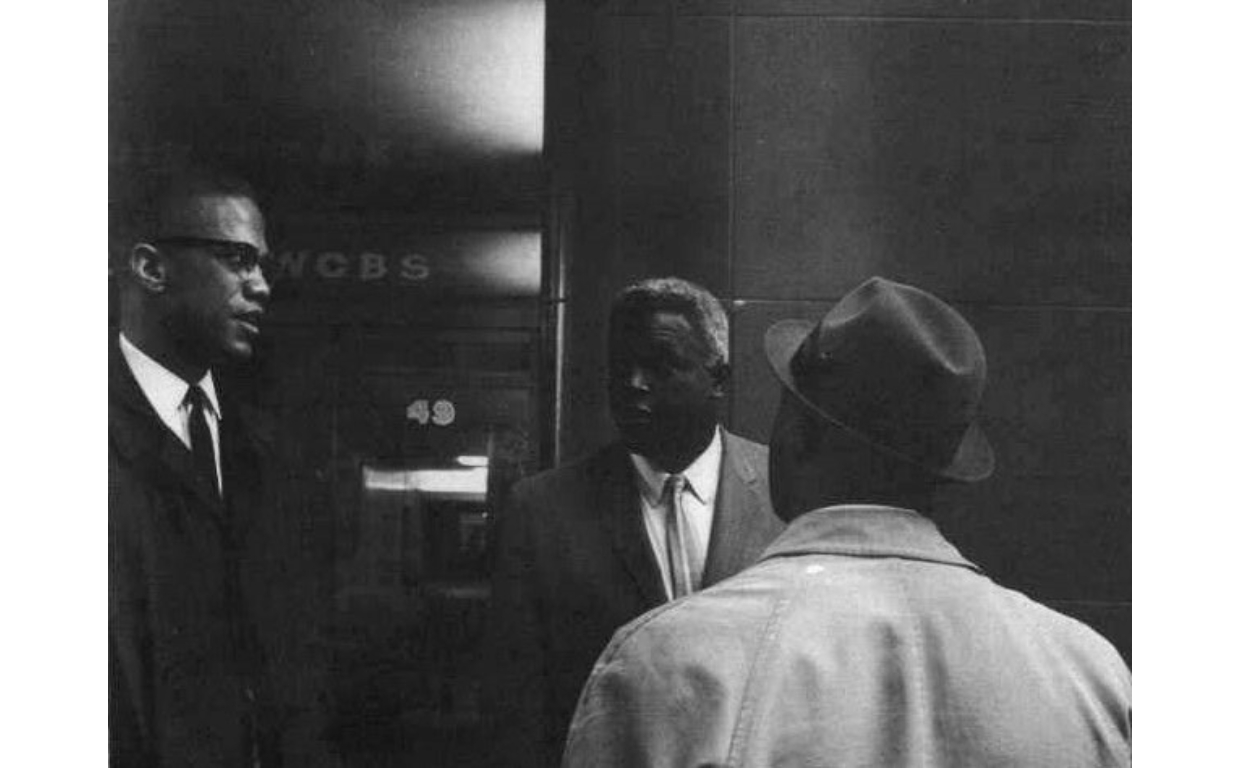

Malcolm X and Jackie Robinson at WWRL studios, July 1962. The New York Public Library

Malcolm, like Jackie, grew up far afield from the streets of Harlem. Born in Omaha, Nebraska in 1925, he moved with his family to Milwaukee, Wisconsin, and then to Lansing, Michigan, while still a young boy. Malcolm’s parents, Earl and Louise Little, were hardworking and part of Marcus Garvey’s Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA). In 1930, after being forced out of the home they purchased in a white neighborhood in Lansing due to local segregation laws and sentiments, Malcolm’s parents bought a home outside of the city. Malcolm’s family continued to have frequent run-ins with local white supremacists, who deemed Malcolm’s father “uppity” and were believed to have been behind Earl Little’s early death in 1931, which was reported as a “streetcar accident.”

The challenges brought on by the death of Malcolm’s father likely led to Malcolm’s trouble with law enforcement. After being imprisoned in Boston on a burglary charge, Malcolm began his conversion to Islam. In 1952, he met Elijah Muhammad, the leader of the Nation of Islam, and began to establish new mosques across the United States, traveling thousands of miles to speak to congregations interested in the Nation of Islam’s teachings. As he did so, he brought a militant message to thousands of Black Americans who were growing cynical about desegregation and Christianity more broadly. As the Civil Rights Movement accelerated, especially in the South, Malcolm and his followers remained skeptical of the usefulness of working toward desegregation, instead developing a Black nationalist practice of self-reliance and self-defense tailored to the urban problems that many Nation of Islam members faced.

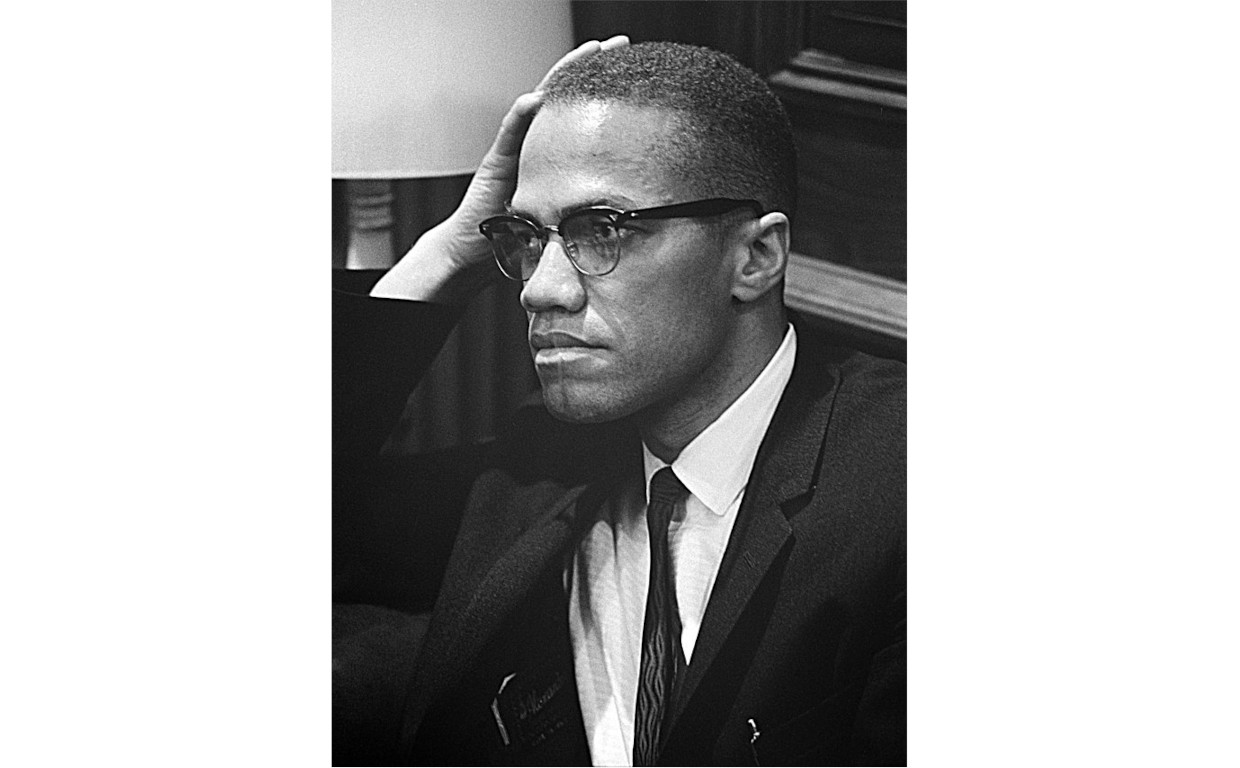

Malcolm X in 1964. Wikimedia Commons

In many ways, Robinson and Malcolm could not have been more different. Although both grew up in poverty, Robinson’s life and career in sports were marked by early successes in desegregation, through which Robinson was able to earn the acceptance (often begrudging) of at least some segments of white America. Malcolm, who was harassed by welfare officials, social workers, and the carceral state for much of his early life, acutely saw the limits of integration into a system that spared little dignity for Black people. As both influencers’ statures grew, they carved out different niches for themselves that were shaped by their personal experiences with race and injustice.

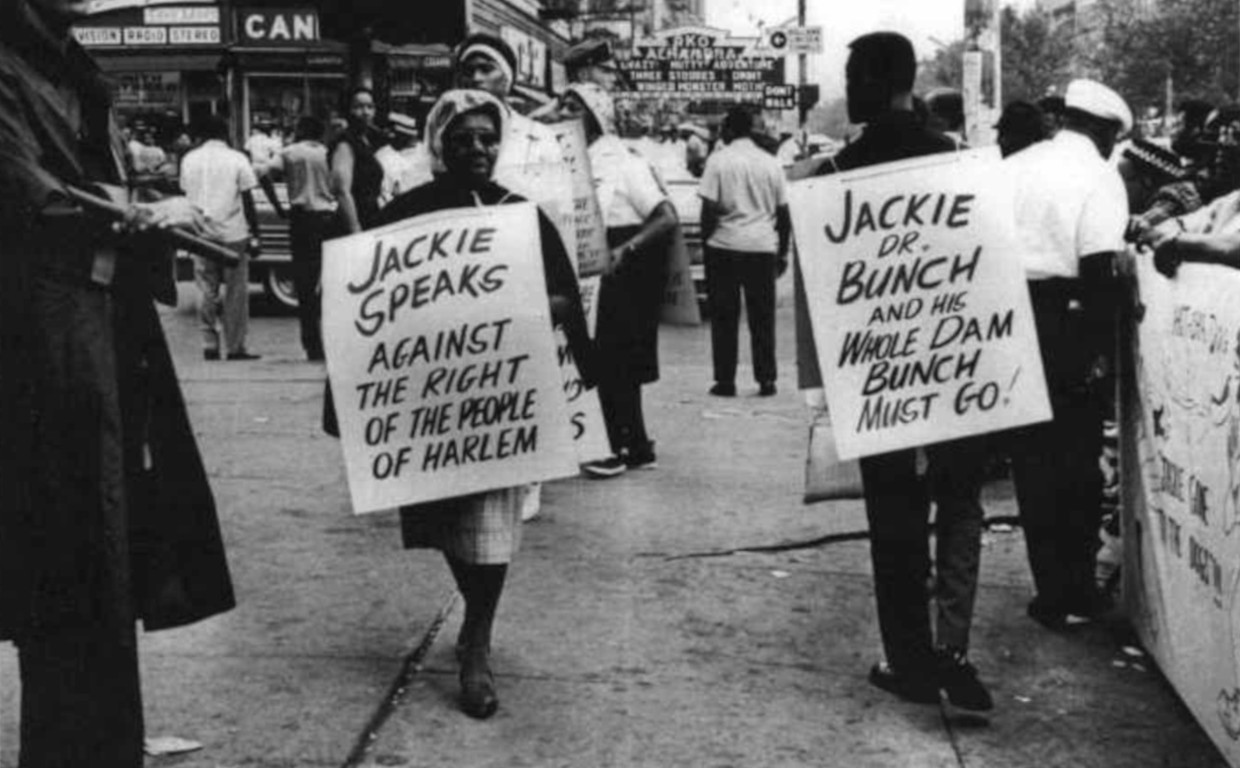

Malcolm X speaks in front of Harlem’s Hotel Theresa in 1963. United Press International

Robinson and Malcolm X first met in 1962, following a heated debate between Jackie and Lewis Michaux, a Black nationalist and bookstore owner in Harlem. What was ostensibly a protest against a new, white-owned steakhouse undercutting a nearby Black business had developed into an ugly series of pickets, with protesters chanting antisemitic slogans against the owners of the new restaurant. In his weekly column in the New York Amsterdam News, Robinson excoriated the protestors, who were supporters of Michaux, advising them not to use bigoted language.1 Robinson engaged Michaux in a heated radio debate after which Michaux compelled the protestors to back off. Malcolm X, himself not a participant, was present at the studio where the debate was held, and spoke candidly with Robinson after.2

After Robinson denounced the protestors for using antisemitic slogans, Michaux’s group began to target the Chock full o’ Nuts in Harlem. Robinson, who was a vice president at Chock at the time, was specifically targeted. The New York Public Library

The next year, Robinson began to use his weekly column in the New York Amsterdam News to establish a greater distinction between himself and the followers of Malcolm X. In July, after Martin Luther King’s car was targeted by Black nationalist egg-throwers in Harlem, Robinson accused Malcolm of leading the barrage, though Malcolm denied any involvement. “Malcolm has just as much right to be opposed to Dr. King as anyone else,” Robinson noted in the Amsterdam News.3 He even went a step further, suggesting that he himself didn’t agree with King’s philosophies: “I am not and don’t know how I could ever be non-violent. If anyone punches me…you can bet your bottom dollar that I will try to give him back as good as he sent.” Robinson, however, continued by noting that King and his integrationist allies represented the will of America’s Black population, rather than Malcolm X. He reiterated that it was “unfair” for King to be attacked this way, and even went as far as to suggest that Malcolm’s movement was being secretly funded by “important aid and sponsorship from outside the race.”4

Robinson continued his salvo that November, when he wrote in defense of Ralph Bunche, after Malcolm accused Bunche (then a well-known U.N. diplomat) of being a voiceless pawn of the American government.5 This column, though it focused primarily on similar attacks made by Congressman Adam Clayton Powell, resulted in a biting response from Malcolm, itself published in the pages of the News: “You became a great baseball player after your White Boss (Mr. Rickey) lifted you to the major leagues…bringing much money through the gates and into [Rickey’s] pockets,” Malcolm began.6 He then continued by outlining other points of disagreement with Robinson: Malcolm condemned Robinson’s 1949 testimony against Paul Robeson in front of the House Un-American Activities Committee, as well as his close associations with Nelson Rockefeller and Richard Nixon, two Republican politicians who were not particularly well-liked by many Black New Yorkers. Finally, Malcolm cautioned Robinson that many of his white allies may someday turn on him and “be the first to put the bullet or the dagger in your back.”

Jackie Robinson poses with New York Governor Nelson Rockefeller in February 1966. When Rocky won re-election in November that year, he underperformed in Black neighborhoods in Brooklyn and Manhattan. Associated Press

Most of all, Malcolm X viewed many of Robinson’s actions as a betrayal. Writing in his autobiography in 1965, Malcolm recounted how closely he followed the early career of Jackie Robinson while he was in prison.7 A decade and a half later, however, he believed that Robinson had gone astray. Though the attacks were personal, Malcolm’s critique reflected the sentiment among some Black New Yorkers that Robinson had grown out of touch with the radical demands of the 1960s. Many Harlemites may have had the same questions about Robinson’s support for these politicians as Malcolm did, or had been hurt by Robinson’s testimony against Robeson years before. Robinson, already used to receiving hate mail of all sorts, received a deluge of letters criticizing his statements against Malcolm X and Adam Clayton Powell.8

In the broadest of senses, the conflict was a clash of politics and wills. Both sides drew new lines in the debate between integration and nationalism that has animated conversations around race since the arrival of the first slaves in the colonies that would become the United States. But it was also a conflict over strategy and tactics, shaped by the rapidly-crystalizing alliances that were forming in the movement. Robinson, for example, often merely accused Malcolm of being a figment of the white media, rather than a leader with a substantial following.9 Such a rhetorical flourish was almost certainly influenced by the politicking of some of his close allies: In 1961, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, on whose board of directors Robinson served, denounced the Nation of Islam as a hate group at its annual convention.10 Later, in 1966, NAACP executive director Roy Wilkins would go on to denounce Black Power more broadly, describing it as the “reverse” of Klan tactics in use in Mississippi.11

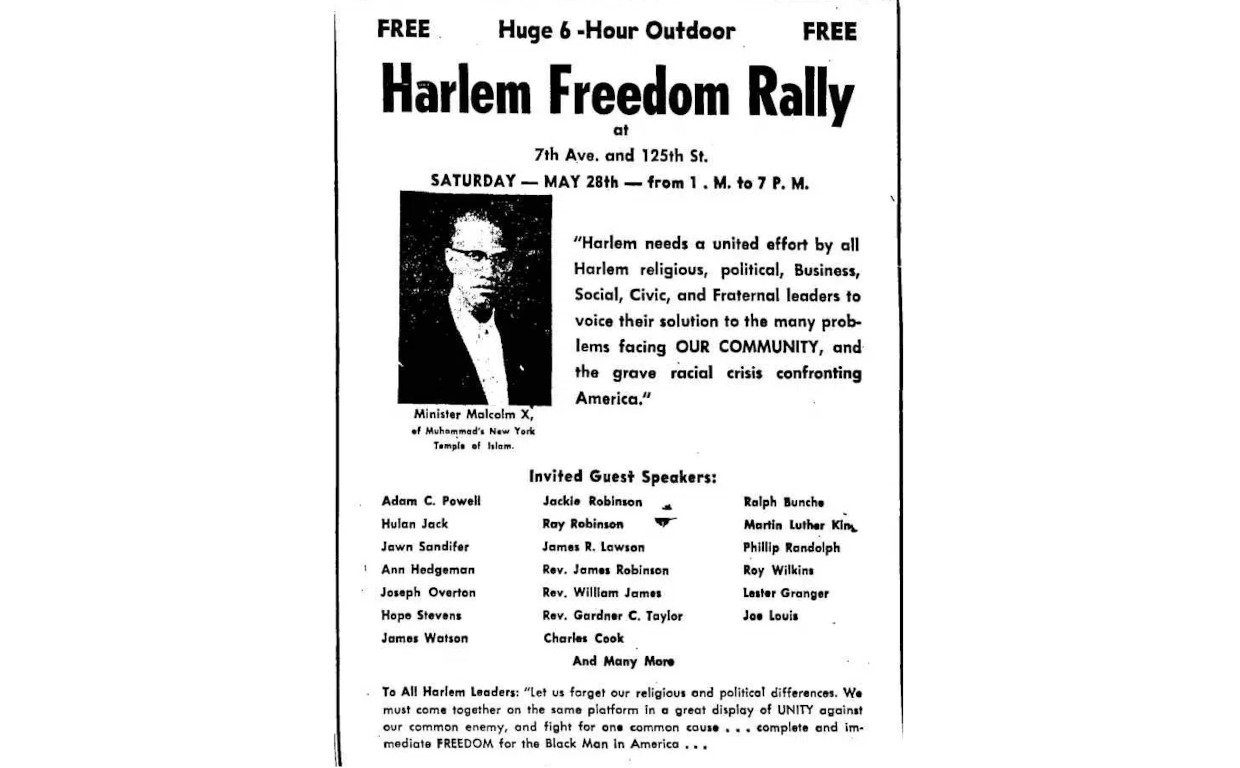

On May 28 1960, Malcolm X hosted a “freedom rally” in Harlem, to which a number of Black celebrities were invited. Robinson did not attend. New York Amsterdam News

Moreover, the conflict was borne out of the reality that neither fully understood how the other earned the support of everyday Black people across the country. Robinson did not yet at this time appreciate the importance of the work the Nation of Islam was able to accomplish around police brutality and accountability within major cities. Moreover, Robinson’s labeling of Malcolm as a firebrand devoid of ideology ignored the Nation’s attempts to ally with more “mainstream” organizations in the early part of the decade.12 Likewise, Malcolm X was generally unwilling to believe in Robinson’s ability to activate marchers and protestors in the cities and towns he visited across the South. By accusing Robinson of being a pawn of “white bosses,” he showed disinterest in the work Jackie had done to support the on-the-ground struggle, especially when it was stagnating locally or in need of money for bail. Both parties accused each other of leading the growing movement in the wrong direction, and said so sharply and openly.

It must be remembered, of course, that the conflict between Robinson and Malcolm X should not be interpreted as an intractable split between parts of the freedom struggle. As contemporary historians such as Timothy Tyson and Charles Cobb have noted, the line between “nonviolence” and “militancy” was often blurred, especially in the Southern states where the movement was being forged.13 Further, Robinson and Malcolm X had more than a few areas of agreement, including the need to fight for Black economic independence.

Robinson also shared Malcolm’s skepticism of Martin Luther King’s emphasis on nonviolence, though he was willing to put aside such tactical differences as he collaborated with King. An astute reader of the New York Amsterdam News would have had access to this debate in real time, and could use the words of the two thinkers to understand their own positionality within a rapidly-shifting political environment.

Jackie Robinson and Lewis Michaux shake hands following their 1962 debate. New York Public Library

Malcolm X was assassinated on February 21, 1965 in the Audubon ballroom in Harlem. By then, he had distanced himself from the Nation of Islam and was increasingly being harassed by its members (as well as federal agents) prior to his murder. Upon his death, Robinson remarked that he rarely agreed with Malcolm’s prescriptions for the movement, though he affirmed that “many of the statements he made about the problems faced by the Negro people were nothing but the naked truth.”14 Mostly, Robinson admired Malcolm as someone who said what he believed, and did so plainly and forcefully, not unlike Robinson himself. The brief eulogy offered by Robinson in print was not one of reluctant acquiescence or false sentimentality. It was simply written out of respect for a man whose powerful voice would help define the struggle for racial equality for decades to come.

Robinson and Malcolm X had radically different visions for Black America in the 1960s. They operated within different channels of the movement and viewed each other with distrust, if not open contempt. Even so, the disagreement was productive: Their conflict, openly bared and syndicated on the pages of Black newspapers, allowed readers themselves to participate in the debates around integration and nationalism that were taking shape. The pair never got a chance to settle their differences. Both died at a fairly young age in the midst of an unfinished struggle for racial justice. Even so, the words they left behind continue to inform conversations about the Black American experience and the reality of disagreement within a mass movement.

To explore the relationship between Jackie Robinson, Malcolm X, and other prominent Harlem civil rights leaders, check out Jackie Robinson’s Harlem available for free online or as a walking tour.

News

Robinson accomplished a great deal on the field, but a museum celebrating his life puts as much focus on his civil rights work.

READ MORE

News

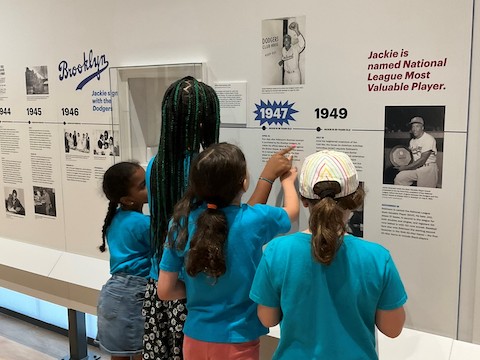

Visitors will also get to explore an immersive experience “to better understand the racism and prejudice Robinson encountered beyond the baseball field, as well as stories of his lasting influence on sports, politics and entertainment today.”

READ MORE

Programs & Events

Get the scoop on new programs and resources for teachers, students, and families!

READ MORE