Closing Early on July 3rd and Closed on July 4th. Plan your visit or become a member today! Speak Out! Student Poster exhibit now on view.

Be inspired. Be challenged.

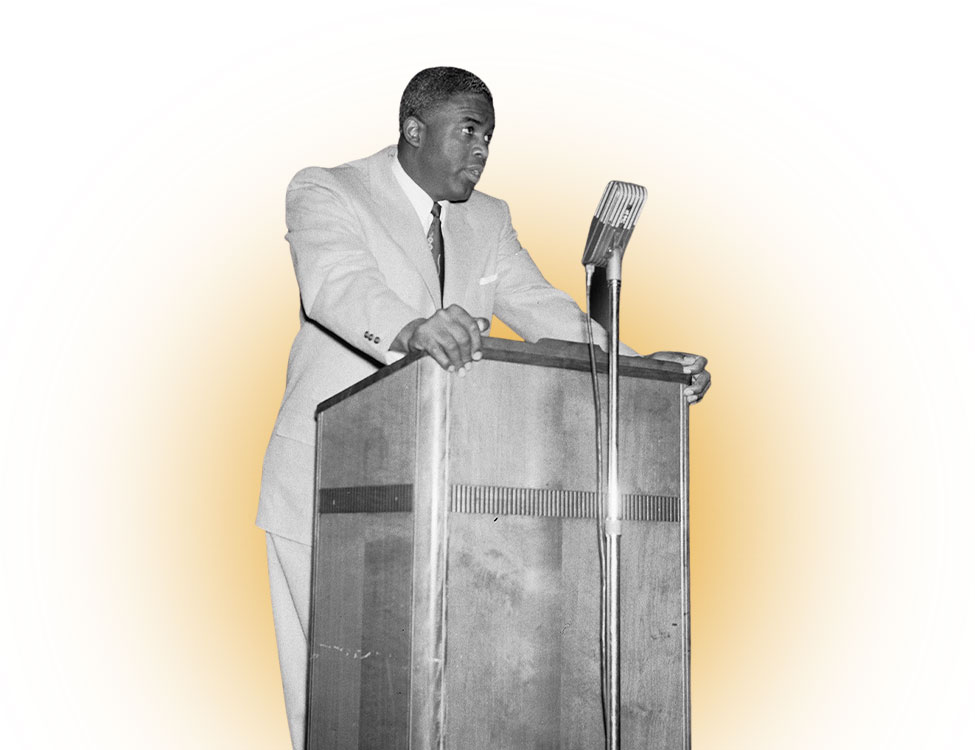

Explore educational resources and experiences that showcase Jackie Robinson’s trailblazing achievements.

SCHOOL PROGRAMS

Your one-stop guide to interactive museum field trips for school and youth groups.

Learn More

STUDENT AND FAMILY RESOURCES

Explore resources to dig deeper into the life and legacy of American icon Jackie Robinson.

Learn More

EDUCATOR RESOURCES

Find activities and resources to complement your museum field trip or classroom instruction.

Learn More