News

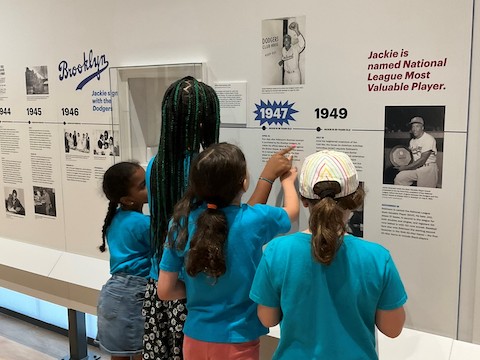

The Jackie Robinson Museum Is About a Lot More Than Baseball

Robinson accomplished a great deal on the field, but a museum celebrating his life puts as much focus on his civil rights work.

READ MOREPlan your visit or become a member today! Admission is free over Presidents’ Day Weekend (Feb 13-15) – Reserve your spot!

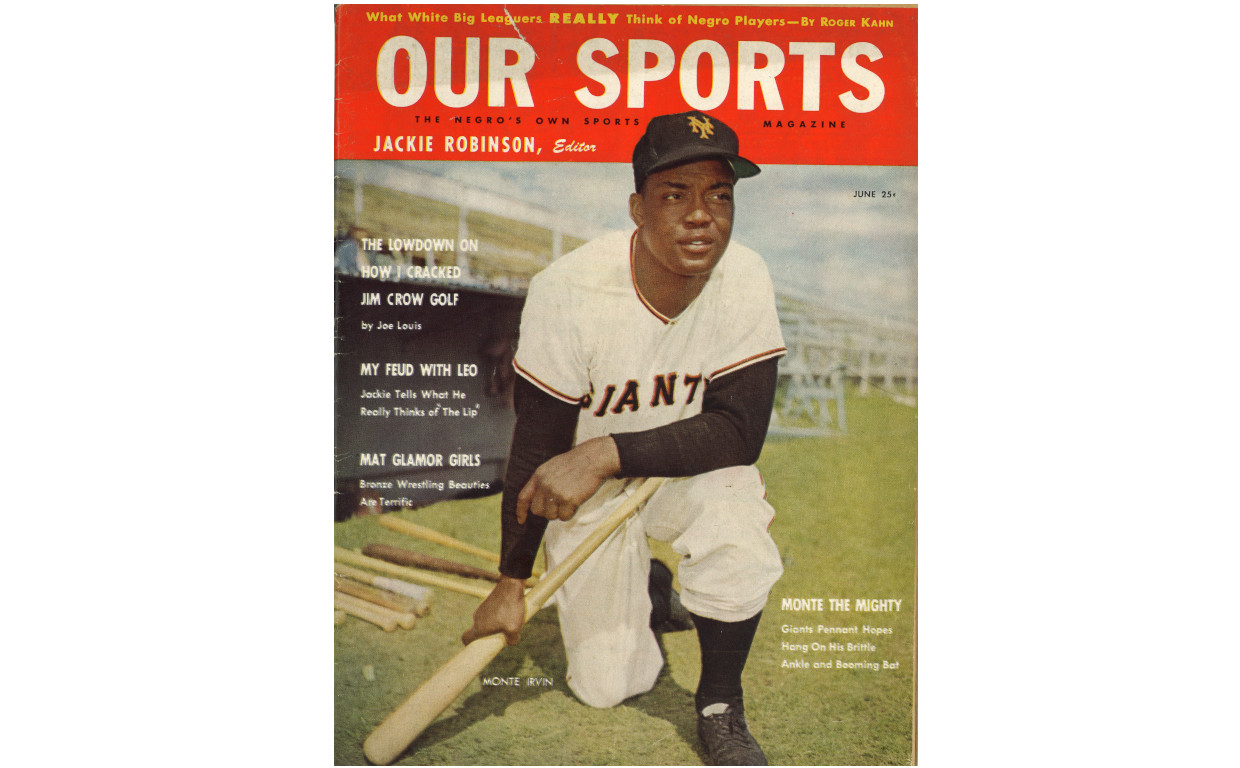

In the spring of 1953, Our Sports, a new and ambitious sports magazine hit the shelves at newsstands around the country. It bore a famous name at the top of the masthead: Jackie Robinson. Writers explored the world of Black sports as they saw it, penning entries on a diverse range of athletes who often went unheralded in the white press. Robinson himself contributed articles on the state of race in baseball. Though the magazine was short-lived, it offered an opportunity for writers to approach issues of race and sports culture through a critical lens. The questions that the magazine raised about how Black athletes are depicted in the media continue to resonate with sports fans today.

June 1953 issue of Our Sports, Jackie Robinson Museum

In February 1953, when news broke in the Pittsburgh Courier that Jackie was tapped as the editor of a new sports magazine, he was just getting ready for his seventh season with the Brooklyn Dodgers and would have little time for journalistic or literary affairs.1 Naturally, the busy Robinson was not the only editor. He was joined by S.W. Garlington, a former New York Amsterdam News columnist and Morehouse alumnus, as executive editor. Jackie, as usual, was more than a famous name. As the first issue went to print, other news sources assured readers that Robinson would “personally pass” on all of the publication’s articles.2 Roger Kahn, who received a hefty commission to write as Jackie, brought flavor to the magazine’s reporting.3 Other notable contributors included Wendell Smith, the Pittsburgh Courier journalist who helped Robinson desegregate baseball, and heavyweight champ Joe Louis, who wrote not about his boxing career but his attempts to desegregate the game of golf.4

Our Sports arrived at a critical time in the history of American sports media. The appetite for photojournalism and newsmagazines was growing rapidly, and sports fans were a particularly profitable constituency. Sport Magazine, launched in 1946, featured color photos of athletes across a wide range of disciplines, bringing images of athletes themselves into readers’ homes on a large scale. Sports Illustrated would publish its first issue in 1954, establishing a durable media empire. A wide range of smaller magazines offered up features and action shots for subscribers as well.

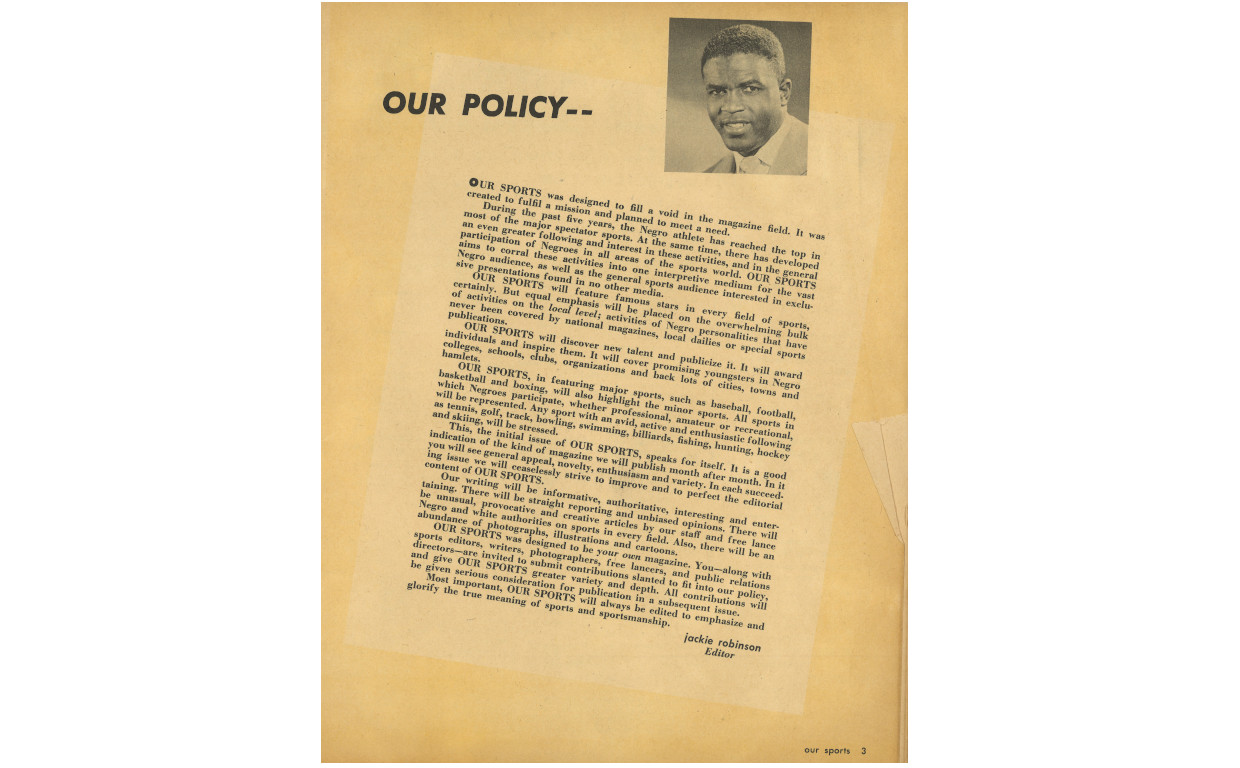

Opening statement of Our Sports, May 1953, Jackie Robinson Museum

The time was ripe for a new publication that was capable of responding both to a growing desire for sports magazines and Black fans’ desire for serious discussions of race and sports. Robinson himself frequently bemoaned both the apathy and mistreatment Black athletes often faced at the hands of the white press. Black athletes were gaining prominence across the entire athletic landscape, including, as the magazine would show, in sports that were slower to integrate than baseball. Robinson said as much on the first page of the inaugural issue: “Our Sports was designed to fill a void in the magazine field,”5 he triumphantly declared. “Over the past five years, the Negro athlete has reached the top in most of the major spectator sports…Our Sports aims to corral these activities into one interpretive medium for the vast Negro audience.”

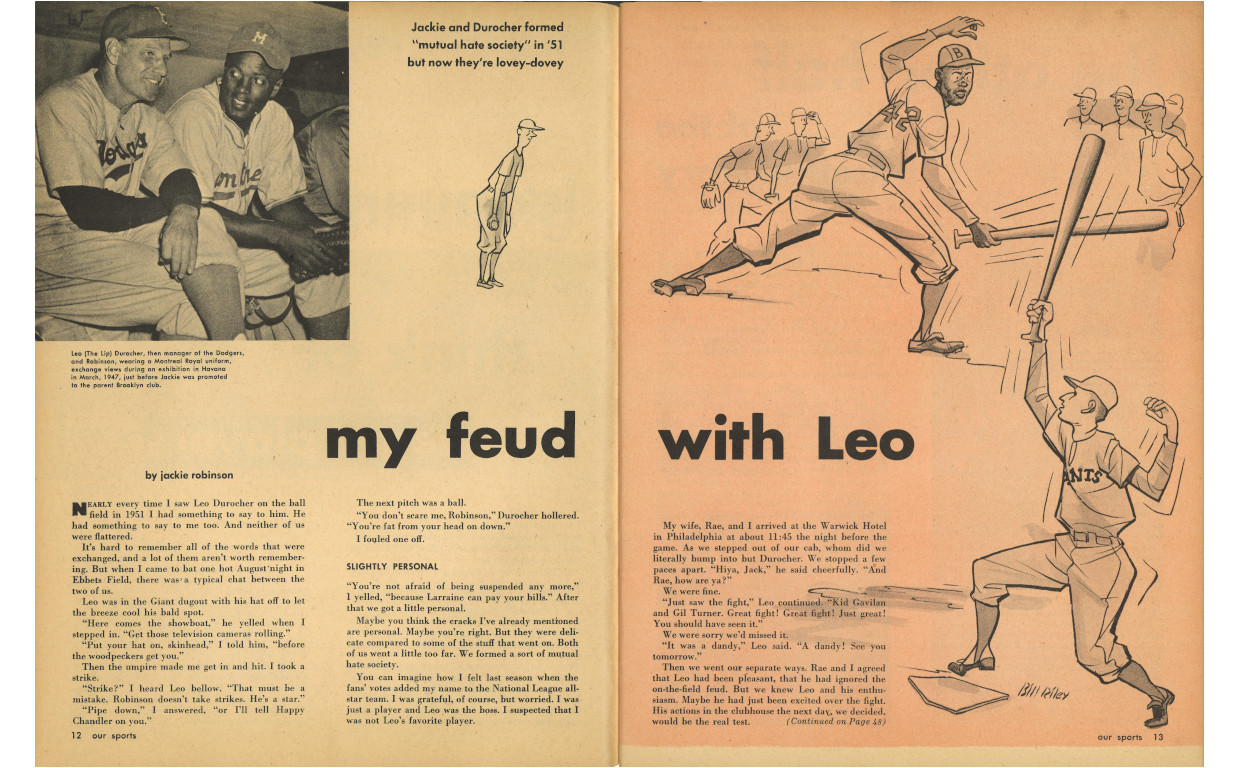

“My feud with Leo” by Jackie Robinson, from the June 1953 issue of Our Sports, Jackie Robinson Museum

At the beginning of most issues, baseball took center stage. Features in Our Sports discussed the chances of the New York Giants during the 1953 campaign, as well as Jackie’s long-running feud with their manager, Leo Durocher. Others examined players’ MVP chances or the interests of their wives. In May, Robinson (complete with a cartoon depicting him as a fortune-teller!) offered his predictions on the 1953 National League season.

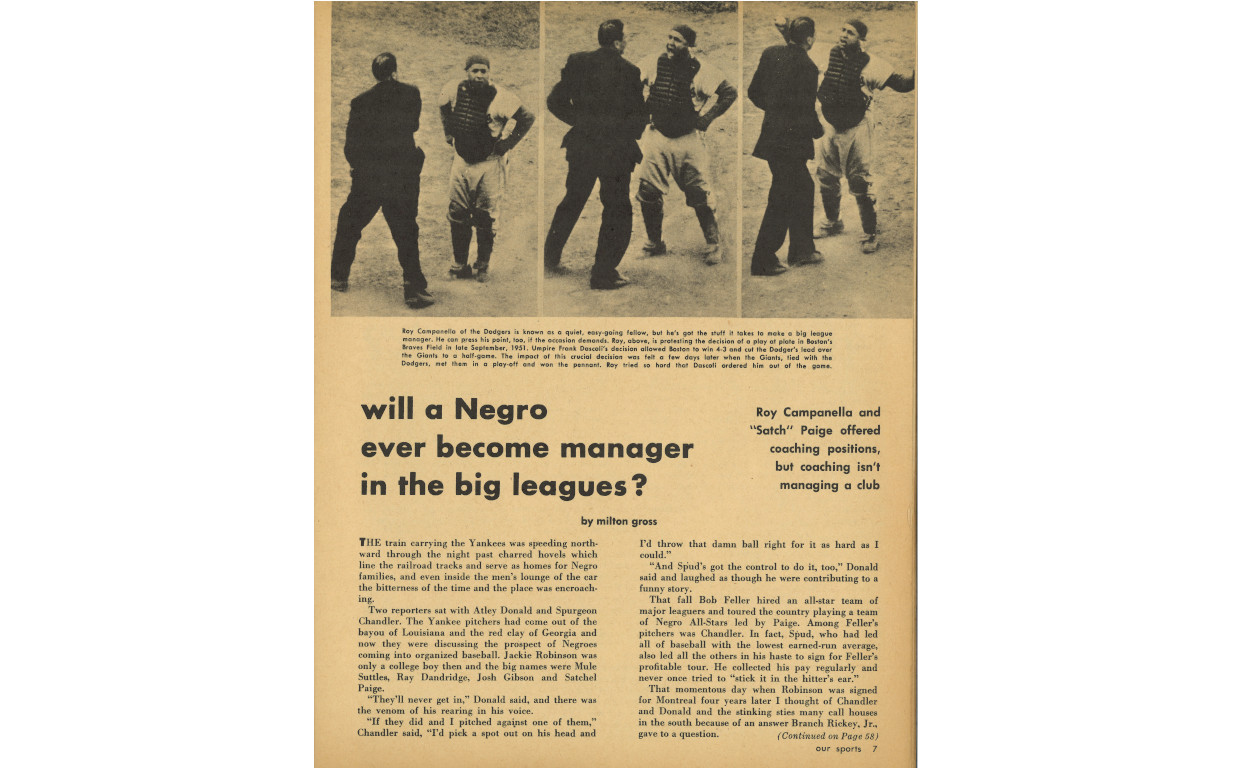

“Will a Negro ever become manager in the big leagues?” by Milton Gross, from May 1953 issue of Our Sports, Jackie Robinson Museum

The first article in that year’s May issue, by New York Post veteran Milton Gross, pointedly asked whether or not there would be a Black manager in the major leagues. This was a key concern for Robinson. He frequently spoke about the need to diversify the upper echelons of baseball and was disappointed when he received no offers to coach after he retired from the game. Gross, who had previously written articles defending Robinson from his many detractors, began his piece with a fiery condemnation of two racist Yankees pitchers who believed, in the 1930s, that the game of baseball would never be integrated. He listed a number of potential managerial candidates while arguing against popular adages that while players would never listen to a Black skipper. “Men play for their salaries,” Gross affirmed. “And they’d play again, even under a Negro manager.”6 The article was published at a time when no Black player had been in the major leagues longer than six seasons. To much of the sports-writing establishment, the subject of Black managers was practically unthinkable. But Gross, Robinson, and the other editors knew that they had a platform to push the envelope. Neither Robinson nor Gross would live to see the first Black manager, Frank Robinson, who did not take the field until 1975 with Cleveland.

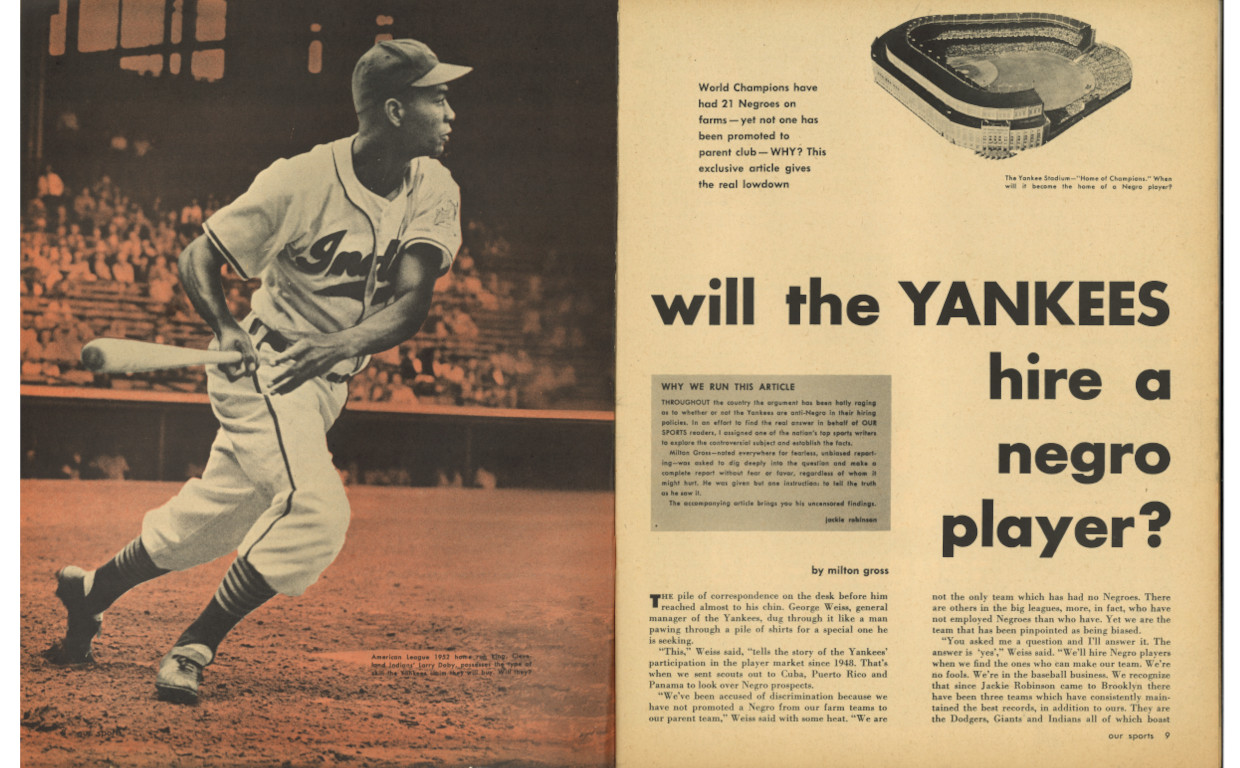

“Will the Yankees hire a negro player?” by Milton Gross, from June 1953 issue of Our Sports, Jackie Robinson Museum

Our Sports also weighed in on other issues close to Robinson. In November 1952, Jackie stirred up controversy after he stated on a television program that the Yankees management was discriminatory towards Black players.7 Indeed, by 1953, the Yankees were one of a handful of teams yet to sign a Black ball player to their major league squad.

In the July issue of Our Sports, Milton Gross tackled the question, examining the Black players in the Bombers’ extensive farm system, including Vic Power and Elston Howard.8 Though he stopped short of making a conclusion (and was sure to highlight vile statements made by the team’s press secretary), Gross certainly painted a rosier picture than the one offered by his editor on television eight months before. Perhaps not unexpectedly, another article appeared in the final issue bemoaning the reality that many skilled Black players spend too much time languishing in the minor leagues.9

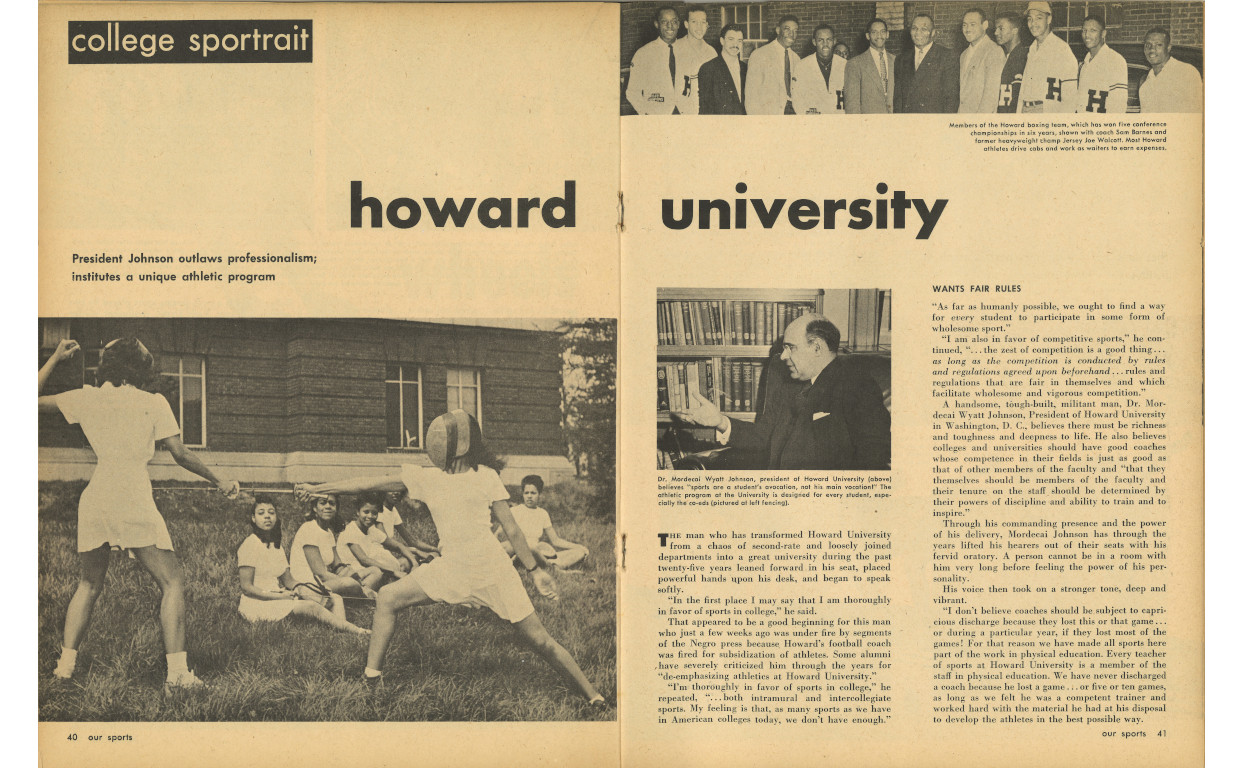

“College Sportrait: Howard University,” from June 1953 issue of Our Sports, Jackie Robinson Museum

Remarkably, baseball was just a sliver of the magazine’s output. Entries about Black sport hunters, bowlers, jockeys, and golfers appeared alongside the biggest names in team sports. It also provided a stage to celebrate the successes of Black universities’ athletic squads. Robinson, a four-sport athlete at UCLA, understood the importance of college athletics not just for the development of professionals, but for the fact that collegiate athletic circuits remained one of the successes of desegregation in American culture thus far.

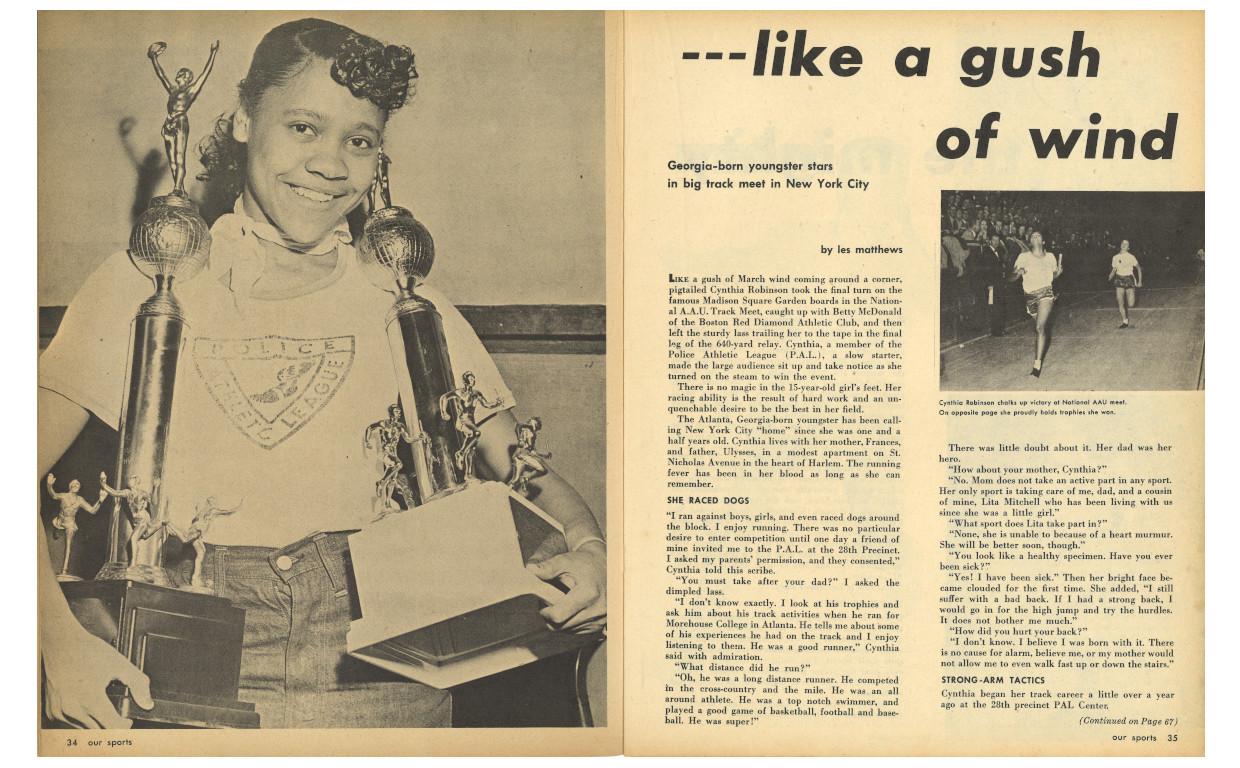

“…like a gush of wind” by Les Matthews, from the May 1953 issue of Our Sports, Jackie Robinson Museum

Equally notable is the magazine’s focus on Black women athletes. As scholar Amira Rose Davis has described, many portrayals of Black women in sports at the time focused heavily on the femininity of the athletes and little on their talent.10 Our Sports resisted this paradigm, depicting the athletes in their athletic gear and highlighting their victories. Again, Robinson and the editors highlighted HBCU athletes and those who were making strides for desegregation in “country club sports” such as tennis and golf. Althea Gibson, whom Our Sports profiled in the June issue, became a frequent collaborator with Robinson, playing as a duo in celebrity golf tournaments in the 1960s.

The balance between celebration and social struggle was key to the magazine’s output. Like many Black magazines and newspapers of its era, Our Sports worked to both catalyze readers’ interest in the ongoing fight for equality while finding joy in the everyday lives of Black Americans. In many articles, athletes’ encounters with Jim Crow, their struggles to desegregate their field, and their relationships with white teammates and opponents were recounted in close detail. But frequently, the authors and editors instead focused on the skill and successes of the players themselves, allowing them to be celebrated not just as pioneering Black athletes, but as equal participants whose batting averages, personal bests, and handicaps counted just as much as anyone else’s—and merited equal celebration and attention from the media.

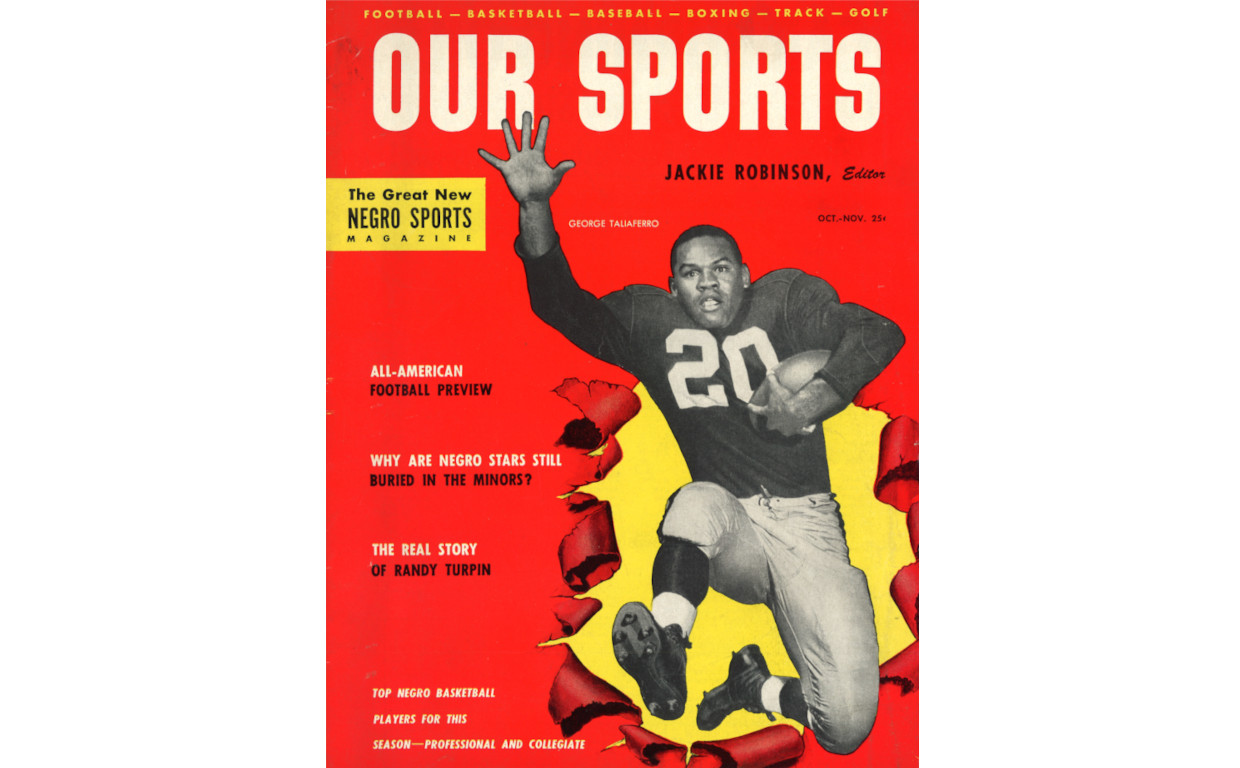

October-November 1953 issue of Our Sports, Jackie Robinson Museum

It was an ambitious project, though sadly, not a durable one. Our Sports only lasted for five issues. After publishing monthly from May to August 1953, the magazine was able to put out an October-November issue later that year before disappearing entirely. Black publications, especially magazines, often operated on shoestring budgets. Our Sports was unable to attract the major advertisers that helped bankroll white publications and was unable to last beyond the baseball season.11

The end of Our Sports did not mark the end of Robinson’s journalistic career. After retiring from baseball, Robinson became a prolific weekly columnist, first with the New York Post in 1959 and later with the New York Amsterdam News through most of the 1960s. There, he continued to write about sports, fighting back against segregation at the New York Athletic Club and writing in support of a threatened boycott of the 1968 Mexico City Olympics. The stories on its pages helped build a world of Black sports at the moment the Jim Crow establishment was falling. The editors and writers knew there was a lot to celebrate—and even more work to be done.

News

Robinson accomplished a great deal on the field, but a museum celebrating his life puts as much focus on his civil rights work.

READ MORE

News

Visitors will also get to explore an immersive experience “to better understand the racism and prejudice Robinson encountered beyond the baseball field, as well as stories of his lasting influence on sports, politics and entertainment today.”

READ MORE

Programs & Events

Get the scoop on new programs and resources for teachers, students, and families!

READ MORE