News

The Jackie Robinson Museum Is About a Lot More Than Baseball

Robinson accomplished a great deal on the field, but a museum celebrating his life puts as much focus on his civil rights work.

READ MOREPlan your visit or become a member today! Get your tickets for January Programs & Events!

On a cool, sunny October afternoon in Washington, D.C., about 10,000 people, mostly Black children and young adults, marched down Constitution Avenue to demand racial equality in education. Four years after the historic Brown v. Board of Education decision called for school desegregation with “all deliberate speed,” advocates and organizers across the country remained disappointed in the lack of progress and the refusal of President Eisenhower’s administration to enforce the law of the land.

At the head of the march was Jackie Robinson, still recently retired from baseball and looking for ways to contribute time, energy, and money to the growing movement. Though the delegation sent to meet with Eisenhower was rebuffed, the march was a demonstration of the viability of mass rallies in the nation’s capital. For Robinson, who was slowly being folded into the inner workings of the struggle for justice, it was a new opportunity to use his voice to inspire others to the cause.

The plan for a march was hatched by A. Philip Randolph at an emergency meeting of civil rights leaders in 1958. Four years on from Brown, segregationists were growing craftier and more effective in their resistance to the largely unenforceable Supreme Court desegregation decisions. Randolph knew from experience that even the threat of a march could bring immense change. In 1941, began to organize march on Washington to demand desegregation in wartime manufacturing. When his demands were hastily met, he called it off. Randolph knew that those in power could be moved by the sound of marching feet. To him, the young marchers would be actors on the stage of history as they brought their demands to the city which was, as he verbosely described it, “the seat of the most sensitive system of public communication and circulation of events and happenings for the information of peoples in the U.S.A. and the world.”1

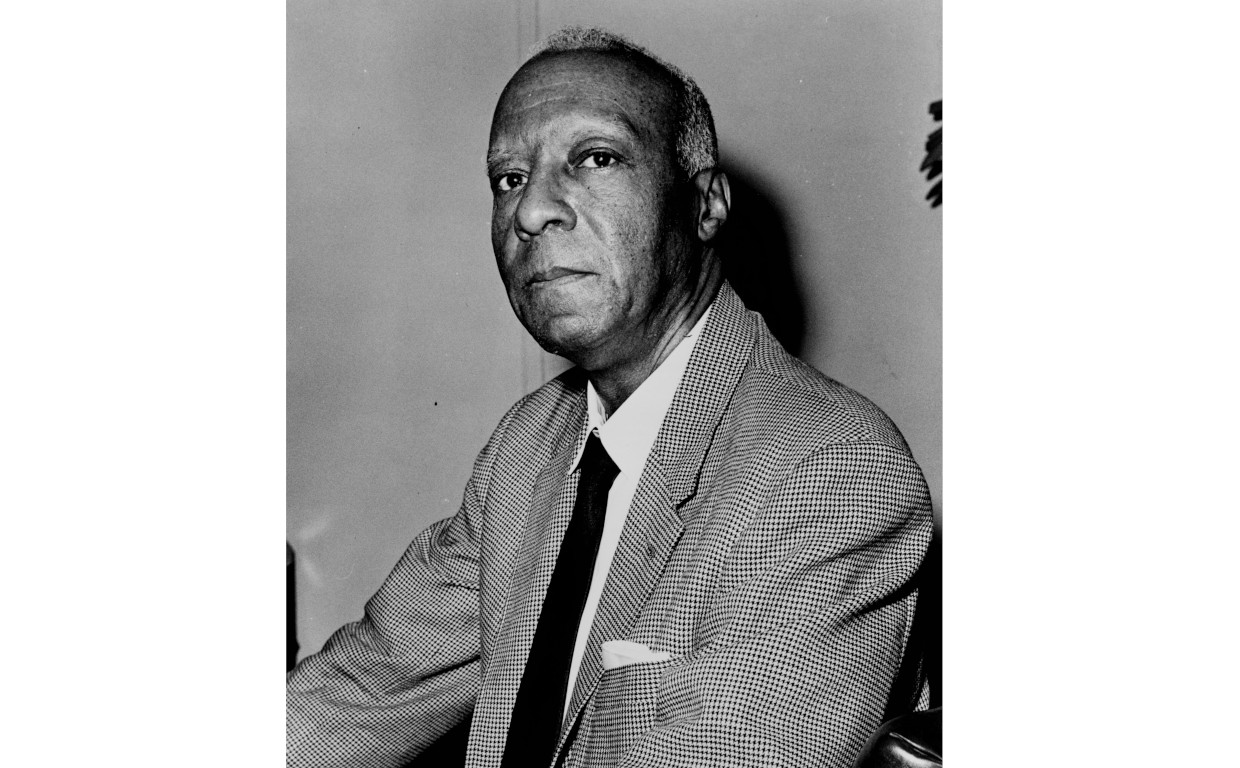

A. Philip Randolph in 1963. New York World Telegram and Sun; Wikimedia Commons

Quickly, Jackie Robinson agreed to be the marshal, alongside Martin Luther King Jr. as chairman.2 The NAACP endorsed the march, and local school, church, and parent groups across the East Coast began to coordinate transportation and care for the children in the city.3 Soon, however, tragedy struck.

During a book signing in Harlem, Martin Luther King was stabbed with a letter opener by a mentally ill woman on September 20. Robinson and Randolph released a statement postponing the march for two weeks, to October 25, to better prepare for the outpouring of support they were anticipating. “The attack…has added a new dimension of importance to the march,” they noted to the press.4 “As a constructive expression of sympathy for [King], many groups are planning to enlarge their participation.” Unions, churches, universities, and even jazz musician Duke Ellington helped pay for buses to transport children and adults to Washington.5

On the day of the march, attendees gathered on Constitution Avenue around 2:30 pm as they prepared to march towards the White House. What was once projected to be a march of a few hundred swelled to over ten times that size, with most reports suggesting that about ten thousand marchers were in attendance. The contingent of notables had swelled as well: In addition to Robinson, the marchers were joined by singer Harry Belafonte, activist Coretta Scott King (speaking on behalf of her recuperating husband), and Minnijean Brown, one of the nine Black students who desegregated Little Rock’s Central High School a year earlier.

Harry Belafonte speaking at a lectern at the Youth March for Integrated Schools. Jackie Robinson can be seen sitting behind him at left. Associated Press

The marchers came to the White House with key demands: They wanted President Eisenhower to withhold education funds from states that refused to integrate schools. They also demanded he fight to end the Senate filibuster, which had recently become a useful tool for stalling civil rights legislation.6

Eisenhower, returning from a golf outing that morning, did not receive the multiracial detachment of students carrying the demands, nor would any of the President’s aides meet with the group. Robinson, speaking to the crowd, was not disturbed. “You have demonstrated to the world that Little Rock is not America,” he declared, referencing the ongoing standoff over desegregation in Arkansas.7 “I am sorry the President has not demonstrated with his actions that he agrees with this demonstration.” Soon, the crowd dispersed

Compared to the marches of the 1960s, a 10,000-student march that was turned back at the gates of the White House might seem like a forgettable or unimportant affair. To this day, it is often a little-discussed footnote in the early history of the movement, overshadowed even by a similar march that took place fewer than six months later. Even so, as Lee Sartain has acknowledged, it was a major step forward in public civil rights protest, demonstrating the viability of mass mobilization around youth issues.8

It was also a major step in the civil rights activities of Jackie Robinson. Prior to the march, his contribution to the movement thus far had largely involved speaking at NAACP galas and registering new members for the organization. This march was Jackie’s first major civil rights mobilization, and it helped establish him not just as a famous ballplayer who was able to raise money, but as someone who could stand on the front lines of rallies and protests—even as the conditions of resistance grew more dangerous in the 1960s.

Jackie and David Robinson join march organizers A. Philip Randolph (center, in bowtie) and Daisy Bates (front center), as well as dancer Julie Robinson and her husband Harry Belafonte (both at right) at the Youth March for Integrated Schools. Getty Images

Though the march drew thousands of supporters, there were some skeptics. Early on, the supporters of the March asked for assistance from the NAACP to help with publicity and funding. Initially, Roy Wilkins, the Executive Director of the organization, questioned the efficacy of such a demonstration. In 1958, the NAACP was by far the largest and best-established organization, and Wilkins was frustrated that a request for sponsorship of the March was made without involving the organization in the planning process.9 Moreover, Wilkins had concerns about the efficacy of the March, as he knew that Congress not being in session would mean less attention would be paid to any rally in Washington. Even so, he threw his support behind the effort as it became clear that it would go forward.

Local NAACP leaders were equally skeptical. The president of the Washington D.C. branch wrote Randolph expressing concern that the March was purposeless, and, even more incredulously, that even the use of the term “integration” could inflame tensions.10 Russell Crawford, the president of the New York City branch, questioned the role of the NAACP in the March entirely, cynically asking why the organization should have involved itself in the first place: “Every promoter of a civil rights activity seems to have the notion that the NAACP should stop whatever it is doing, however important, and become the host to that particular cause,” he bemoaned, highlighting the difficult work in which the organization was already engaged.11 Indeed, as Wilkins had mentioned, the busy schedule of the NAACP‘s activity during the fall left little room for new work. When the march was unsuccessful in its stated aim, many of the critics thought they had been proven correct.

Demonstrators carry banners at the Youth March for Integrated Schools. Marchers from the New York University chapter of the NAACP can be seen at center left. Washington Area Spark

Despite this opposition from leaders, however, NAACP chapters were instrumental in turning their members out for the march. They were so successful, in fact, that when a second march was planned for May 1959, Gloster Current, the NAACP director of branches recommended the organization wholeheartedly support the even while harboring skepticism about the usefulness of these demonstrations.12

With a proven formula and more support, the second Youth March for Integrated Schools drew a crowd of 26,000, including Jackie Robinson, who made his second appearance as a marshal. This time, a delegation was able to deliver a petition to the White House. A. Philip Randolph, Jackie Robinson, and the thousands of others were vindicated in their choice of tactics. By 1963, when 250,000 marchers descended on the National Mall for the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, the power of the marches to mobilize supporters was apparent to all.

For Robinson, the Youth March for Integrated Schools was an opportunity to grow the movement in new and important ways. For over a decade, Robinson had served as a role model for Black youth across the country as he fought against segregation on the baseball diamond. Now, Robinson stepped up to be a leader of the youth movement as the struggle for civil rights began to take on a mass character. The Youth March was Robinson’s first step into the streets of Washington as a leader of a major rally. He knew the struggle for first-class citizenship for all was just beginning, and he was ready to play a new role on the world’s largest stage.

News

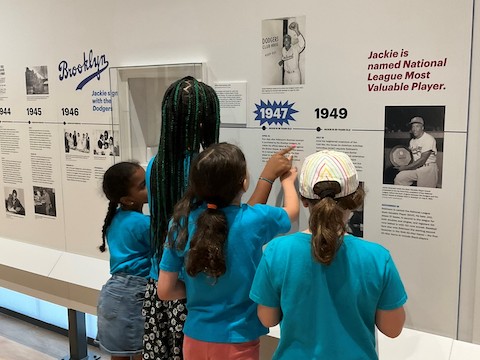

Robinson accomplished a great deal on the field, but a museum celebrating his life puts as much focus on his civil rights work.

READ MORE

News

Visitors will also get to explore an immersive experience “to better understand the racism and prejudice Robinson encountered beyond the baseball field, as well as stories of his lasting influence on sports, politics and entertainment today.”

READ MORE

Programs & Events

Get the scoop on new programs and resources for teachers, students, and families!

READ MORE