Story Types: Jackie's Story

How do we tell the stories behind the artifacts at the Jackie Robinson Museum? Sometimes the answers to our questions can be found as close to our doors as Harlem or Flatbush. In many cases, however, the stories begin in cities and towns hundreds of miles away from the confines of Ebbets Field. On July 19, 1947, Charles McConnell, a Black teenager living in Johnson City, Tennessee, picked up his pen and began to write one of those stories.

That day, McConnell wrote a brief letter to Jackie Robinson, who was in the fourth month of his first season with the Brooklyn Dodgers. By July, Robinson had hit his stride and was proving that he was truly big-league material. His victories on the field traveled across the radio waves to reach Americans of all backgrounds. McConnell, who enjoyed sports of all types, was following Robinson closely. And like many youngsters around the country, he knew that something important was happening in America.

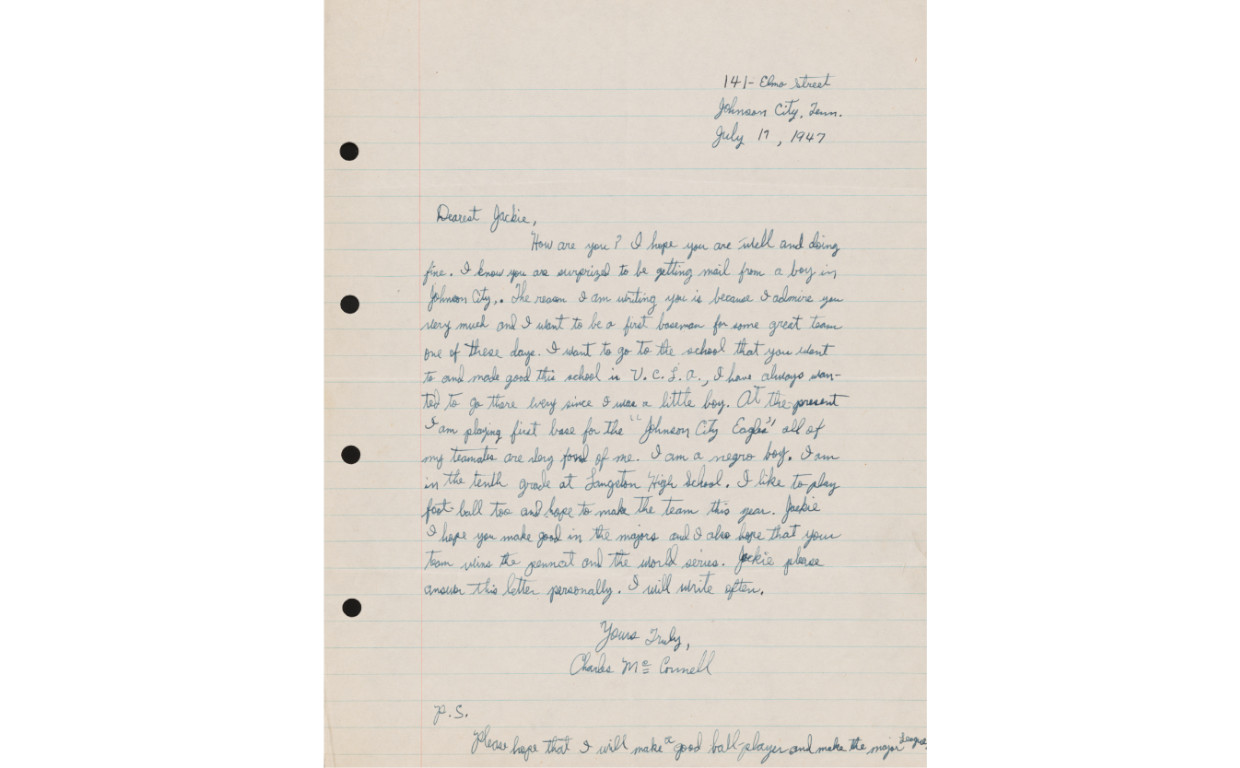

Charles McConnell’s letter to Jackie Robinson, July 19, 1947, Library of Congress. View transcript below.

Dearest Jackie, How are you? I hope you are well and doing fine. I know you are surprised to be getting mail from a boy in Johnson City. The reason I am writing you is because I admire you very much and I want to be a first baseman for some great team one of these days. I want to go to the school that you went to and make good the school in U.C.L.A. I have always wanted to go there ever since I was a little boy. At the present I am playing first base for the “Johnson City Eagles” all of my teammates are very fond of me. I am a negro boy. I am in the tenth grade at Langston High School. I like to play football too and hope to make the team this year. Jackie I hope you make good in the majors and I hope that your team wins the pennant and the world series. Jackie please answer this letter personally. I will write after.

A reproduction of this heartfelt letter, originally preserved in Dodger secretary Arthur Mann’s papers in the Library of Congress, is on display at the Jackie Robinson Museum. On its own, the letter is a warm tribute to the awe-inspiring power Robinson had, even for those who never saw him play. In summer 2025, however, a resident of Johnson City saw the letter and connected the Jackie Robinson Museum with the story of a man who used sports to bring together his own community in an era of progress and change. Working with the Langston Center in Johnson City, Tennessee (a community organization located in the former high school McConnell once attended), the Jackie Robinson Museum can now tell the story of a man whose life was touched by Robinson’s on-field triumphs and used that inspiration to fight for the betterment of society as a whole.

Elva Morrison, sister of Charles McConnell, describes the culture of Johnson City during her childhood. Courtesy of Johnson City, TN

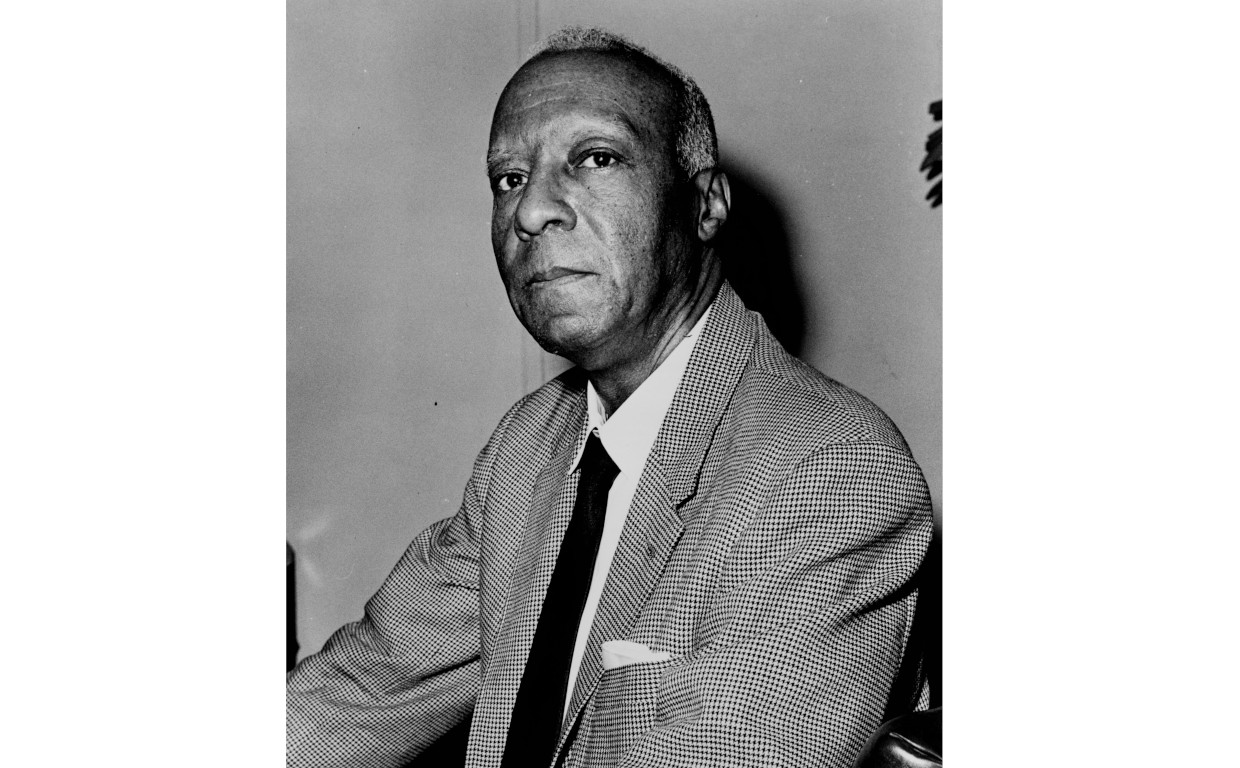

Like Robinson, McConnell developed a love of sports from a young age in a city where segregation was pervasive, but not absolute. “Our neighborhood was always integrated,” noted McConnell’s sister Elva Morrison in a recent interview. “Except the schools…we were just neighbors!” Langston High School, at the time, served the city’s small Black population. There, McConnell played first base and developed a love of baseball, especially Dodgers stars Jackie Robinson and Roy Campenella, whom he could follow in the newspapers and on the Dodgers’ national radio network. Soon, McConnell joined the Army during the Korean War and returned to Johnson City after his stint in the service.

McConnell began his career as an official in 1964 and became the first African American in the region to call basketball and football games. The job, according to Danny Williams, a deacon at McConnell’s Friendship Baptist Church, was not easy. “He was in demand because he was a good official,” Deacon Williams noted. But he added, “Going to a neighboring county that might not have been as welcoming [to a Black referee] and being in charge, blowing the whistle, and calling a foul on their boys? He would talk about having to get out the back door sometimes, and get to safety.” Demanding respect as an authority while being a trailblazer on one’s own terms was very difficult, something that Black officials at all levels learned in that era.

Deacon Danny Williams discusses Charles McConnell’s officiating career and the challenges he faced. Courtesy of Johnson City, TN

Even so, he was able to command the respect of the eastern Tennessee athletic community, becoming an in-demand official for both high school and college games. He took his work seriously, and, according to Rev. Lester Lattany of Friendship Baptist, would pray at home over missed calls and other mistakes that come with the territory of being an official. He served as a mentor to both younger officials and the students under his watch, reminding them of the importance of the world beyond the court and gridiron. Like Robinson himself, who frequently volunteered as a coach at the Harlem YMCA, McConnell saw the power of sports as a tool to build community for young people, and he worked to build that community for over forty years. In honor of his service, McConnell was inducted into the Tennessee Secondary School Athletic Association Hall of Fame in 2022.

Rev. Lester Lattany of Friendship Baptist Church discusses the respect Charles McConnell earned as a referee and the legacy he left behind. Courtesy of Johnson City, TN

Charles’s wife Ann also led civil rights efforts in Johnson City as well. In 1965, their family sued the school system for slow-walking desegregation, and won. Both were members of their local NAACP chapter, and both surely benefitted from Jackie Robinson’s fundraising work for the organization throughout the 1950s and 1960s. The McConnells fought Jim Crow in their own hometown, and they helped build a more equitable society for the generations that followed. Many of the students in the games McConnell refereed were the first beneficiaries of the desegregated schools he fought for.

Charles McConnell passed away in 2022 at the age of 89. His letter to Jackie is a reminder of how Jackie Robinson’s incredible story can only fully be understood in the context of the millions of people who followed his 1947 season, hoping that he would make the grade as a big-league ballplayer. Children like McConnell followed Robinson’s story because they knew that change was in the air. Robinson’s triumphs carried along the airwaves to cities and towns across America, and inspired others to take up his mantle and use sports as a catalyst for change in their own communities.

McConnell prepares a jump ball during a high school basketball game. Johnson City News and Neighbor

McConnell’s story is also a testament to the power of doing critical historical work within our own communities. Not everyone got the opportunity to write a letter to Jackie Robinson, but millions of Americans have stories about how their lives were shaped by Jackie and other titans of the movement in the forties, fifties, and sixties. Artifacts in the Jackie Robinson Museum are not just jerseys on mannequins and plaques on walls—they carry the stories of Robinson’s triumphs and struggles—and the hopes and dreams of the people who followed every stolen base and stump speech. These stories exist in every community, and it is up to us to find and preserve them, just as Charles McConnell’s church and community have done with his life and work on and off the field.

Special thanks to Adam Dickson, Nicholas Harrison, Pauline Douglas, Elva Morrison, Danny Williams, Rev. Lester Lattany, Friendship Baptist Church, the Langston Centre, and Johnson City, TN community for their time and support in the process of producing this post.

On a cool, sunny October afternoon in Washington, D.C., about 10,000 people, mostly Black children and young adults, marched down Constitution Avenue to demand racial equality in education. Four years after the historic Brown v. Board of Education decision called for school desegregation with “all deliberate speed,” advocates and organizers across the country remained disappointed in the lack of progress and the refusal of President Eisenhower’s administration to enforce the law of the land.

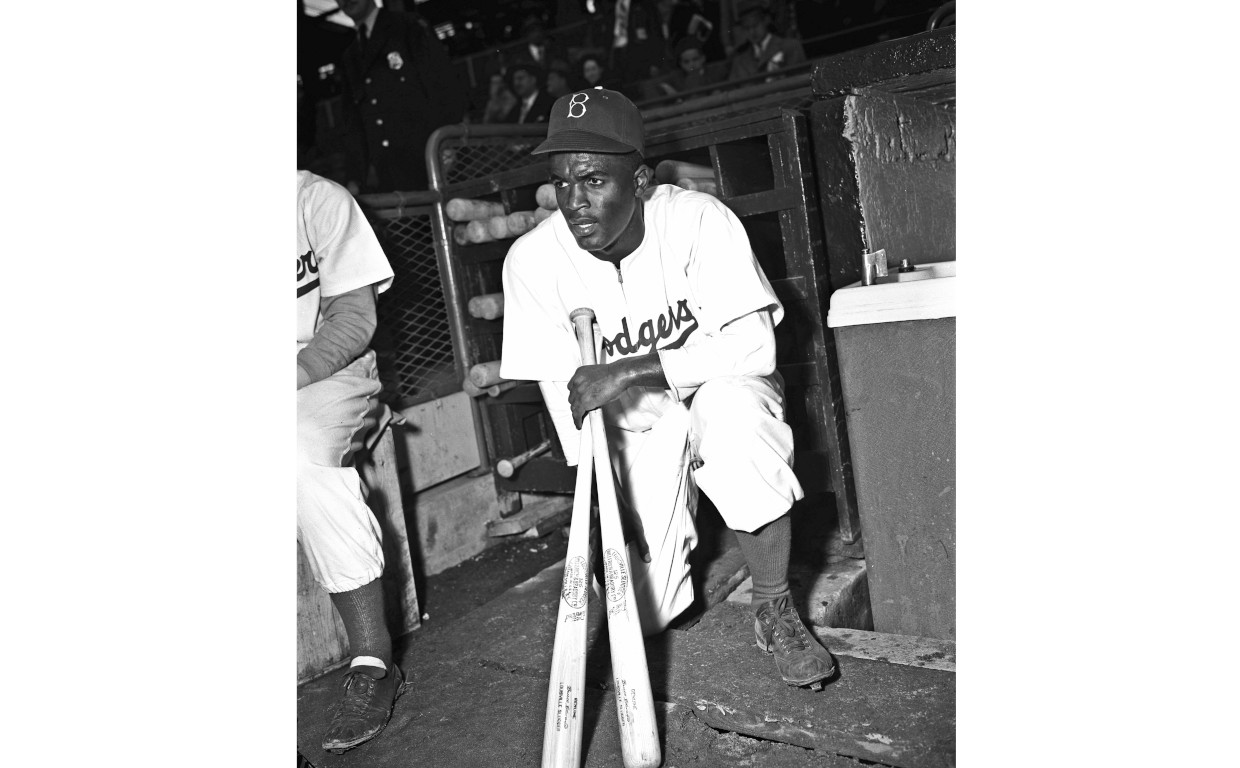

At the head of the march was Jackie Robinson, still recently retired from baseball and looking for ways to contribute time, energy, and money to the growing movement. Though the delegation sent to meet with Eisenhower was rebuffed, the march was a demonstration of the viability of mass rallies in the nation’s capital. For Robinson, who was slowly being folded into the inner workings of the struggle for justice, it was a new opportunity to use his voice to inspire others to the cause.

The plan for a march was hatched by A. Philip Randolph at an emergency meeting of civil rights leaders in 1958. Four years on from Brown, segregationists were growing craftier and more effective in their resistance to the largely unenforceable Supreme Court desegregation decisions. Randolph knew from experience that even the threat of a march could bring immense change. In 1941, began to organize march on Washington to demand desegregation in wartime manufacturing. When his demands were hastily met, he called it off. Randolph knew that those in power could be moved by the sound of marching feet. To him, the young marchers would be actors on the stage of history as they brought their demands to the city which was, as he verbosely described it, “the seat of the most sensitive system of public communication and circulation of events and happenings for the information of peoples in the U.S.A. and the world.”1

A. Philip Randolph in 1963. New York World Telegram and Sun; Wikimedia Commons

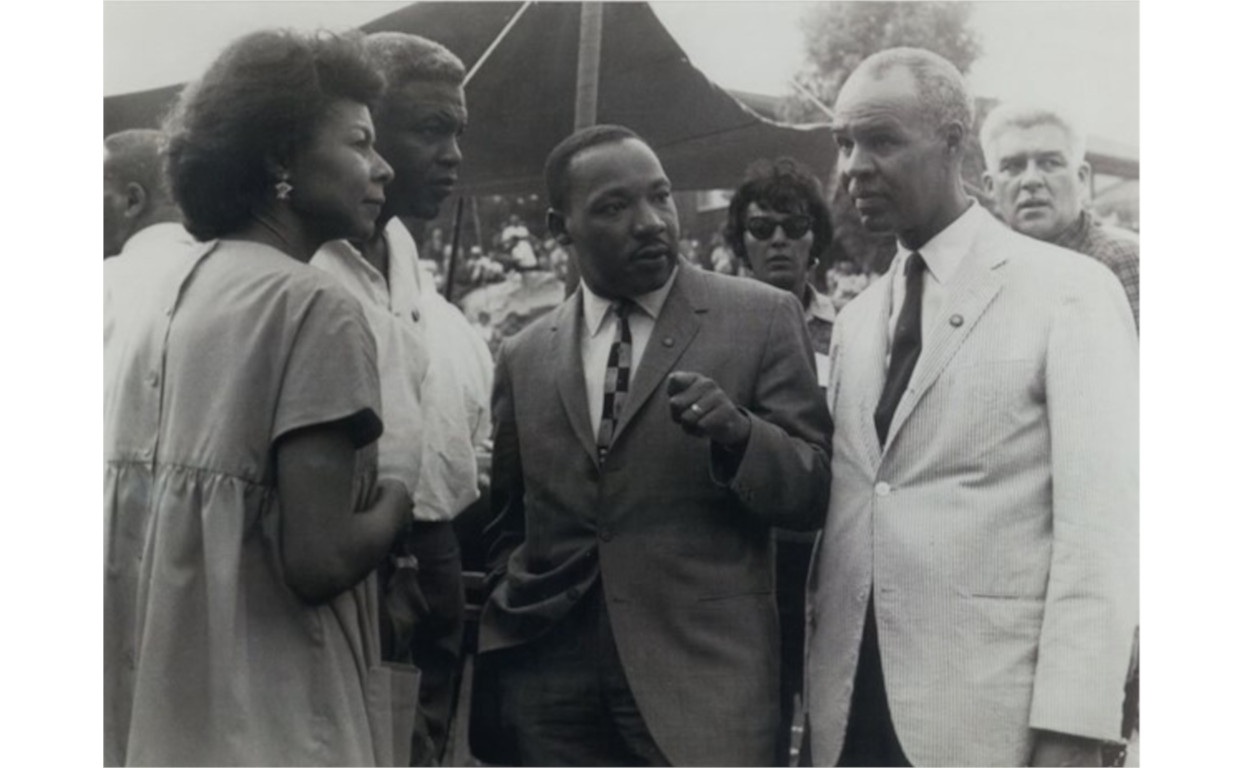

Quickly, Jackie Robinson agreed to be the marshal, alongside Martin Luther King Jr. as chairman.2 The NAACP endorsed the march, and local school, church, and parent groups across the East Coast began to coordinate transportation and care for the children in the city.3 Soon, however, tragedy struck.

During a book signing in Harlem, Martin Luther King was stabbed with a letter opener by a mentally ill woman on September 20. Robinson and Randolph released a statement postponing the march for two weeks, to October 25, to better prepare for the outpouring of support they were anticipating. “The attack…has added a new dimension of importance to the march,” they noted to the press.4 “As a constructive expression of sympathy for [King], many groups are planning to enlarge their participation.” Unions, churches, universities, and even jazz musician Duke Ellington helped pay for buses to transport children and adults to Washington.5

On the day of the march, attendees gathered on Constitution Avenue around 2:30 pm as they prepared to march towards the White House. What was once projected to be a march of a few hundred swelled to over ten times that size, with most reports suggesting that about ten thousand marchers were in attendance. The contingent of notables had swelled as well: In addition to Robinson, the marchers were joined by singer Harry Belafonte, activist Coretta Scott King (speaking on behalf of her recuperating husband), and Minnijean Brown, one of the nine Black students who desegregated Little Rock’s Central High School a year earlier.

Harry Belafonte speaking at a lectern at the Youth March for Integrated Schools. Jackie Robinson can be seen sitting behind him at left. Associated Press

The marchers came to the White House with key demands: They wanted President Eisenhower to withhold education funds from states that refused to integrate schools. They also demanded he fight to end the Senate filibuster, which had recently become a useful tool for stalling civil rights legislation.6

Eisenhower, returning from a golf outing that morning, did not receive the multiracial detachment of students carrying the demands, nor would any of the President’s aides meet with the group. Robinson, speaking to the crowd, was not disturbed. “You have demonstrated to the world that Little Rock is not America,” he declared, referencing the ongoing standoff over desegregation in Arkansas.7 “I am sorry the President has not demonstrated with his actions that he agrees with this demonstration.” Soon, the crowd dispersed

Compared to the marches of the 1960s, a 10,000-student march that was turned back at the gates of the White House might seem like a forgettable or unimportant affair. To this day, it is often a little-discussed footnote in the early history of the movement, overshadowed even by a similar march that took place fewer than six months later. Even so, as Lee Sartain has acknowledged, it was a major step forward in public civil rights protest, demonstrating the viability of mass mobilization around youth issues.8

It was also a major step in the civil rights activities of Jackie Robinson. Prior to the march, his contribution to the movement thus far had largely involved speaking at NAACP galas and registering new members for the organization. This march was Jackie’s first major civil rights mobilization, and it helped establish him not just as a famous ballplayer who was able to raise money, but as someone who could stand on the front lines of rallies and protests—even as the conditions of resistance grew more dangerous in the 1960s.

Jackie and David Robinson join march organizers A. Philip Randolph (center, in bowtie) and Daisy Bates (front center), as well as dancer Julie Robinson and her husband Harry Belafonte (both at right) at the Youth March for Integrated Schools. Getty Images

Though the march drew thousands of supporters, there were some skeptics. Early on, the supporters of the March asked for assistance from the NAACP to help with publicity and funding. Initially, Roy Wilkins, the Executive Director of the organization, questioned the efficacy of such a demonstration. In 1958, the NAACP was by far the largest and best-established organization, and Wilkins was frustrated that a request for sponsorship of the March was made without involving the organization in the planning process.9 Moreover, Wilkins had concerns about the efficacy of the March, as he knew that Congress not being in session would mean less attention would be paid to any rally in Washington. Even so, he threw his support behind the effort as it became clear that it would go forward.

Local NAACP leaders were equally skeptical. The president of the Washington D.C. branch wrote Randolph expressing concern that the March was purposeless, and, even more incredulously, that even the use of the term “integration” could inflame tensions.10 Russell Crawford, the president of the New York City branch, questioned the role of the NAACP in the March entirely, cynically asking why the organization should have involved itself in the first place: “Every promoter of a civil rights activity seems to have the notion that the NAACP should stop whatever it is doing, however important, and become the host to that particular cause,” he bemoaned, highlighting the difficult work in which the organization was already engaged.11 Indeed, as Wilkins had mentioned, the busy schedule of the NAACP‘s activity during the fall left little room for new work. When the march was unsuccessful in its stated aim, many of the critics thought they had been proven correct.

Demonstrators carry banners at the Youth March for Integrated Schools. Marchers from the New York University chapter of the NAACP can be seen at center left. Washington Area Spark

Despite this opposition from leaders, however, NAACP chapters were instrumental in turning their members out for the march. They were so successful, in fact, that when a second march was planned for May 1959, Gloster Current, the NAACP director of branches recommended the organization wholeheartedly support the even while harboring skepticism about the usefulness of these demonstrations.12

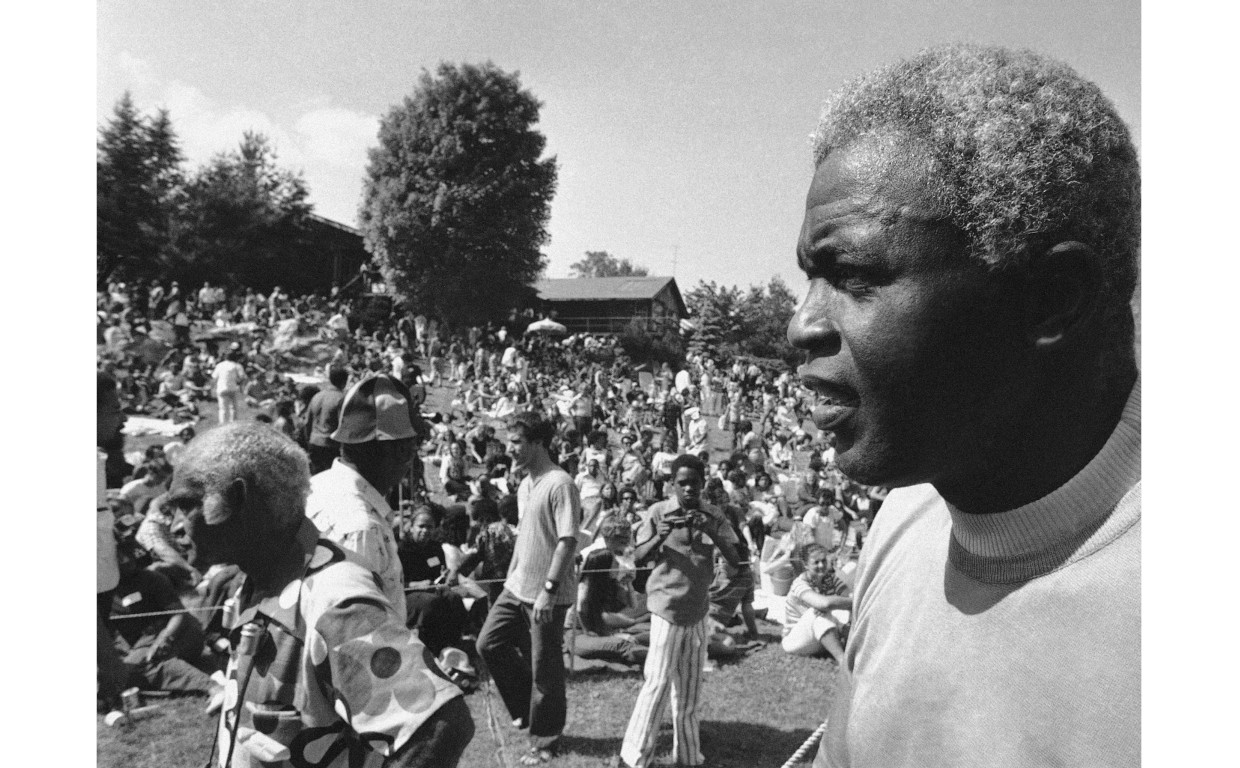

With a proven formula and more support, the second Youth March for Integrated Schools drew a crowd of 26,000, including Jackie Robinson, who made his second appearance as a marshal. This time, a delegation was able to deliver a petition to the White House. A. Philip Randolph, Jackie Robinson, and the thousands of others were vindicated in their choice of tactics. By 1963, when 250,000 marchers descended on the National Mall for the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, the power of the marches to mobilize supporters was apparent to all.

For Robinson, the Youth March for Integrated Schools was an opportunity to grow the movement in new and important ways. For over a decade, Robinson had served as a role model for Black youth across the country as he fought against segregation on the baseball diamond. Now, Robinson stepped up to be a leader of the youth movement as the struggle for civil rights began to take on a mass character. The Youth March was Robinson’s first step into the streets of Washington as a leader of a major rally. He knew the struggle for first-class citizenship for all was just beginning, and he was ready to play a new role on the world’s largest stage.

References

- Philip Randolph, “Why the Youth March For Integrated Schools?,” 1958, Civil Rights Movement Archive, https://www.crmvet.org/docs/581000_ymis_apr-why.pdf.

- “Students Set To March On Capitol Asking Integration,” Chicago Defender (Chicago, Ill., United States), September 18, 1958.

- “Randolph Proposes March on Washington,” Pittsburgh Courier (1955-1966), City Edition (Pittsburgh, Pa., United States), September 13, 1958.

- “Assault On Rev. King Postpones Youth March,” Philadelphia Tribune (Philadelphia, Penn., United States), September 27, 1958.

- “Duke Ellington Donates Bus for Youth March,” The St. Louis American (St. Louis, Missouri, United States), October 2, 1958.

- “Integration Rally in Washington Claims Rebuff by President,” Daily Boston Globe (Boston, Mass., United States), October 26, 1958.

- Edward Peeks, “10,000 in Youth March Say ‘Integrate,’” Baltimore Afro-American (Baltimore, Md., United States), November 1, 1958.

- Lee Sartain, “‘LET THE CHILDREN LEAD’?: The Youth Marches for Integrated Schools, Washington, DC, 1958 and 1959,” Journal of Civil and Human Rights 7, no. 2 (2021): 29–59.

Roy Wilkins, “Letter from Roy Wilkins to A. Philip Randolph Expressing Skepticism about the Youth March for Integrated Schools,” September 12, 1958, Part 24: Special Subjects, 1956-1965; Youth March on Washington, NAACP Papers. - Eugene Davidson, “Letter from Eugene Davidson to A. Philip Randolph Advising against the Youth March for Integrated Schools,” September 24, 1958, Youth March for Integrated Schools in Washington, D.C., including communist participation, A. Philip Randolph statement, NAACP cooperation, and program outline, pages 28-29, NAACP Papers, Part 24: Special Subjects, 1956-1965.

- Russell P. Crawford, “You And The NAACP,” New York Amsterdam News (1943-1961), City Edition (New York, N.Y., United States), November 8, 1958.

- Sartain 2021, 47

Perhaps no other day lives on in Brooklyn Dodger infamy as does the afternoon of October 3, 1951. What was once a thirteen-game lead over the New York Giants, the Bums’ hated crosstown rival, disappeared in a flash as the Giants’ Bobby Thomson hooked a walk-off home run over the Polo Grounds’ left-field fence. For Jackie Robinson, his Dodgers, and the thousands of Brooklynites who lived and died with the team, the loss was the latest insult in a long line of crushing defeats and missed chances dating back over decades of play. Ralph Branca, the unfortunate Dodger hurler who surrendered the homer, would be haunted for the rest of his life by one at bat. Though the “Shot Heard ‘Round the World,” as it came to be known, was a landmark moment in Dodger history, two of its key participants, Branca and Robinson, shared a friendship that could not be defined a single, heartbreaking home run.

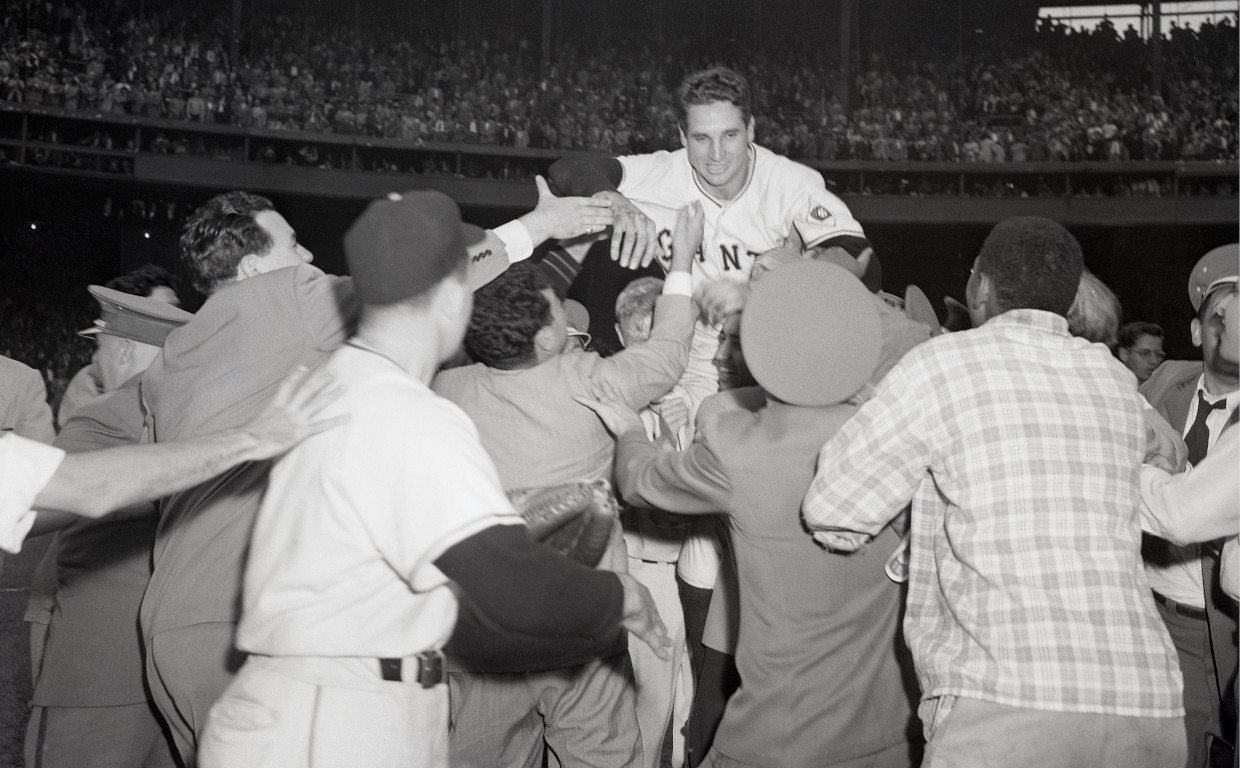

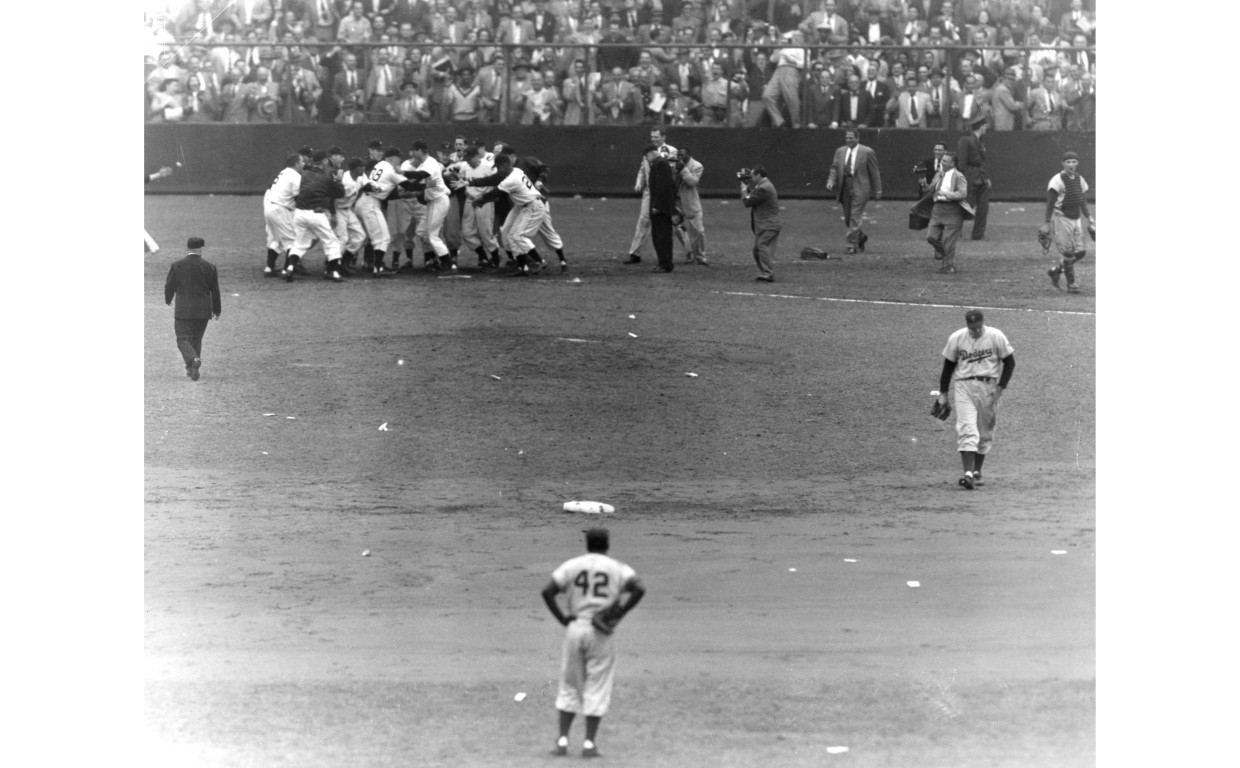

Bobby Thomson is carried off the field by adoring fans after his home run sent the New York Giants to the 1951 World Series. Getty Images

Prior to the modern era of convoluted playoff brackets and Wild Card showdowns, the World Series was played between the winners of the American and National Leagues. It was as simple as that. Find yourself at the top of your league at the end of September and you’ll punch your ticket to the Fall Classic. If there was a tie, there would be a three-game playoff to determine the winner. For most of the 1951 season, the Brooklyn Dodgers looked like the sure victors. After taking the lead in the National League in the middle of May, it was hard to deny that they were the team to beat. Beginning in August, however, the Giants began to surge. After a sixteen-game winning streak and stellar play down the stretch, they found themselves in a tie with the Dodgers before the final game of the season.

(left to right) Duke Snider, Gil Hodges, Jackie Robinson, Pee Wee Reese, and Roy Campanella pose together in June 1951. This season, Jackie’s fifth, was a banner year for the Dodgers offense. Robinson himself had his best year, and Campanella won his first of three Most Valuable Player awards. Getty Images

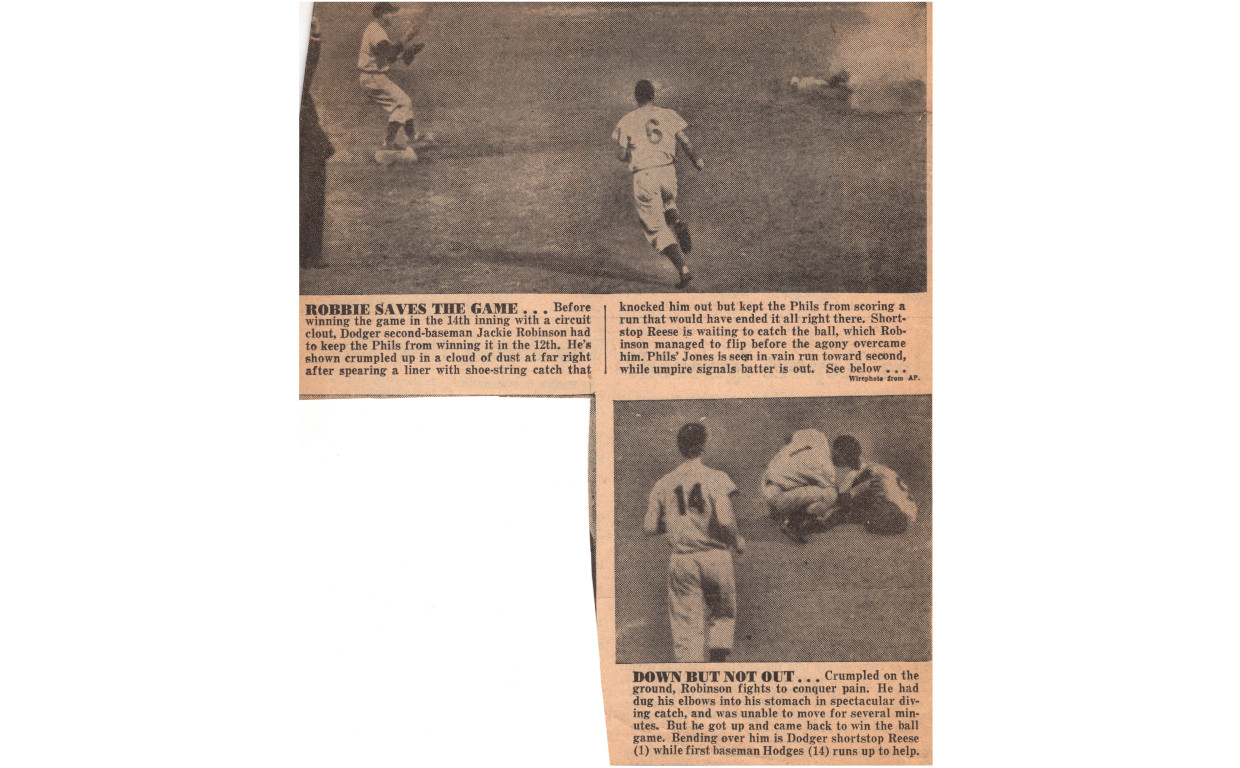

If it had not been for Jackie Robinson’s heroics, the Dodgers’ season would have ended then and there. After the Giants defeated Boston in quick fashion, Brooklyn needed a win over Philadelphia to even force a playoff. The game began disastrously. The Dodgers found themselves down 6 to 1 at the end of three innings but were able to tie the game at eight apiece at the end of nine. With the bases loaded at the bottom of the twelfth, the Phillies’ Eddie Waitkus smashed a liner up the middle that was sure to be a walk-off hit. Miraculously, Robinson, ranging from his position at second, leaped to grab the ball, nearly knocking himself out cold as he slammed into the hard dirt of Shibe Park. “I flipped the ball away so everyone would know I had caught it,” Robinson said, a prudent move, given that the catch could have been disputed.1 After he lay on the ground for five minutes, manager Charlie Dressen and the Dodgers trainer were able to help him off the field. In the top of the fourteenth, Robinson, having been revived with a piece of ammonia-soaked cotton, returned to the batter’s box and hit a homer into the left field stands.2 Speaking to the Herald Tribune after the game, Robinson declared it the greatest home run he ever hit.3 For a moment, the Bums’ pennant hopes were saved.

In this pair of Associated Press wirephotos, Robinson can be seen lying in a cloud of dust after his season-saving catch in the bottom of the twelfth inning against the Phillies. Newspaper unknown, Jackie Robinson Museum Collection

The playoff with the Giants began the next day. For Brooklyn fans, there was plenty of reason to be worried. The pitching staff was tired, and the momentum was obviously with New York. The first two games, split between Ebbets Field and the Giants’ Polo Grounds, were less than eventful. The Giants won the first game 3 to 1, with Ralph Branca himself earning the loss. Clem Labine, who had proven effective for the Dodgers down the stretch, pitched a 10–0 shutout in the second. The stage was set for a winner-take-all showdown in Manhattan, with the victor going on to face the fearsome New York Yankees in the World Series.

The final game started on a positive note for Brooklyn. With Pee Wee Reese at second base in the top of the first inning, Jackie Robinson singled to left, giving the Dodgers their first lead of the afternoon. For the next seven innings, pitchers reigned. Don Newcombe, who had pitched five innings of the marathon against Philadelphia just three days earlier, cruised through the first eight innings, giving up only a single run. A three spot in the top of the eighth for Brooklyn, including an intentional walk for Robinson, put the Dodgers up 4 to 1.

What followed was one of the most fateful managerial decisions in baseball history, one that has been endlessly debated by fans to this day. The Giants’ Bobby Thomson was coming to the plate, representing the winning run. When Dodgers manager Charlie Dressen strode to the mound to replace Newcombe, he was faced with a choice: would he bring in Carl Erskine, who had pitched effectively that season but was troubled with nagging arm problems, or would he turn to Ralph Branca, who had pitched two days prior in the Dodgers’ first loss? Dressen chose Branca, and the rest is history. On the second pitch of the at-bat, Thomson whacked a fastball over the Polo Grounds’ short left-field porch, sending the fans into delirium and the Giants to the World Series for the first time since the Great Depression.4

Click to watch the Shot Heard ‘Round the World, courtesy of MLB

In hindsight, the decision to go with Branca was itself questionable. Though the Dodgers were the first team to employ a statistician, Dressen was likely unaware that Thomson had hit Branca effectively throughout the entire season. Unrelated to Branca, of course, was the fact that the Giants also had an elaborate electronic mechanism for surreptitiously stealing opposing catchers’ signs from center field, though it remains unclear whether or not Thomson knew what pitch was coming, or if that information was of use to him.5

Newcombe, by this point, was tiring, and it began to show in the bottom of the ninth. The first two Giants, Alvin Dark and Don Mueller, reached on singles. After inducing a popout from former Negro Leagues great Monte Irvin, Whitey Lockman doubled to left, and Newcombe’s night was over.

Thomson’s home run was likely aided by the highly unusual dimensions of the Polo Grounds, on display in this 1923 photo. The distance from home plate to the left field foul pole was only 279 feet, meaning that the Shot Heard ‘Round the World might have only been heard in left fielder Andy Pafko’s glove had the game been played at Brooklyn’s Ebbets field…or any modern-day ballpark!

Robinson watched the entire play from his position at second base. While most of his teammates began to leave the field as soon as the ball left the field of play, Robinson stayed behind, creating one of the most striking images in baseball history. Already known as one of baseball’s most fearsome competitors, Robinson stood with his hands on his hips, eyes down, as he made sure Thomson touched every base. Only when the Giants began their celebration around home plate did he finally leave his post.

Jackie Robinson stands with his hands on his hips as Bobby Thomson’s teammates gather around home plate. At right, Ralph Branca walks dejectedly from the mound. Getty Images

For all the broken hearts from Gowanus to Bed-Stuy, none were as shattered as that of Ralph Branca. When he returned to the dugout, almost none of his teammates came to console him. For a brief moment, Branca was alone in defeat. “Hardly anyone knows what happened afterward,” Branca later remarked.6 “I’m sitting there by my locker with my head down and Jackie comes over to me and taps me on the shoulder and says: ’Don’t hang your head. If it wasn’t for you we wouldn’t even have been here’…[W]hat made it significant was the fact that Jackie was the only player to come over and talk to me after that game. He was not just a teammate. He was my best friend on that team.”

Ralph Branca and Jackie Robinson vigorously shake hands after inking their 1948 contracts with the Brooklyn Dodgers. Associated Press

Robinson took this role seriously. When he joined the Dodgers in 1947, he was often described as the loneliest man in baseball. Few of his teammates spoke to him, and he was seldom included in the card games and shared meals that defined the culture of ball players on the road. Ralph Branca was one of Robinson’s first real allies on the team. He was the only Dodger to stand beside Robinson on Opening Day, and he slowly brought Robinson into the social life of the team. Soon, Jackie began to confide in Branca during the difficult period in 1947, when opponents were hurling beanballs and slurs as he fought to integrate the game. When Robinson joined Branca in the locker room after the loss to the Giants four years later, it was not merely an empty gesture to console the losing pitcher after a tough outing. It was a debt repaid.

Though the Dodgers were sent home, there was still more baseball to be played in New York. The Giants would go on to lose the World Series to the Yankees in rather forgettable fashion, being defeated in six games. Soon, the Dodgers would find themselves back on top again, winning the National League pennant in 1952 and 1953. Ralph Branca, unfortunately, did not return to form. After injuring himself in spring training in 1952, he never pitched with the same effectiveness he had throughout most of the 1951 season.

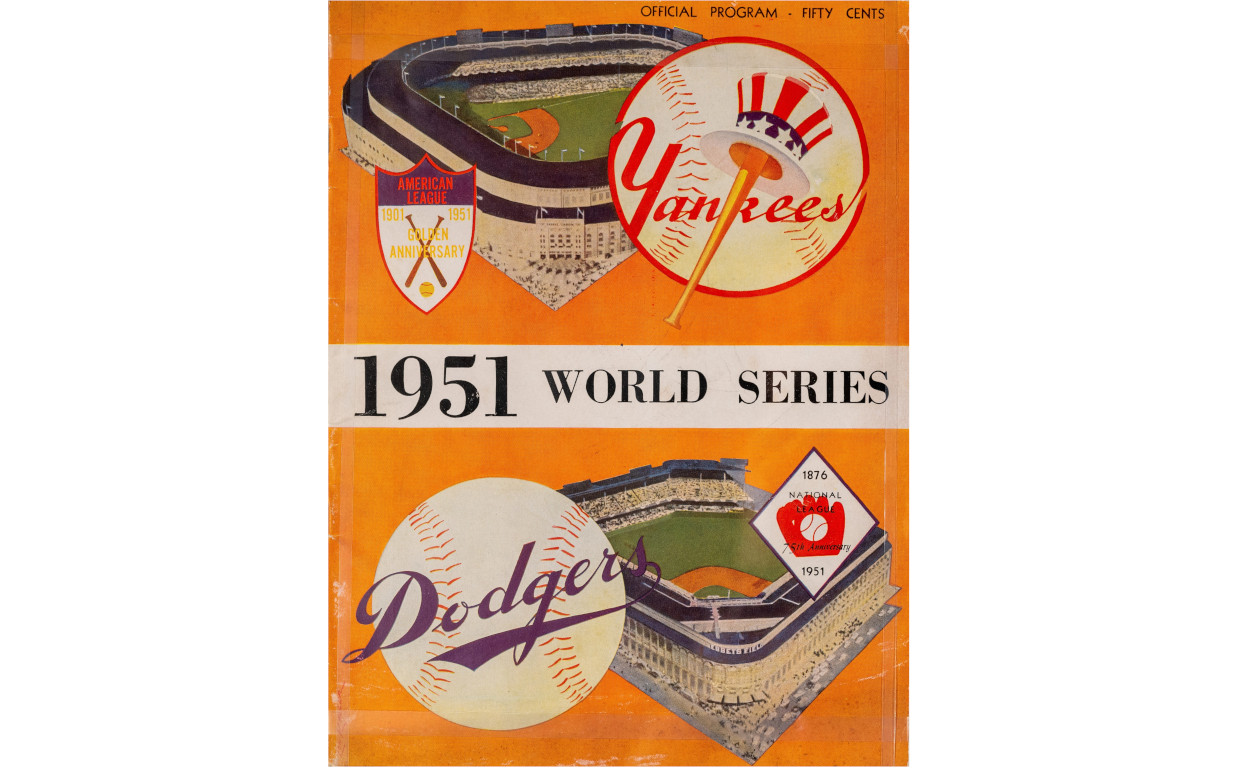

The Brooklyn Dodgers were at one point thirteen games ahead of the Giants in the quest for the pennant. This pre-printed program for a Dodgers-Yankees World Series was never used. walteromalley.com

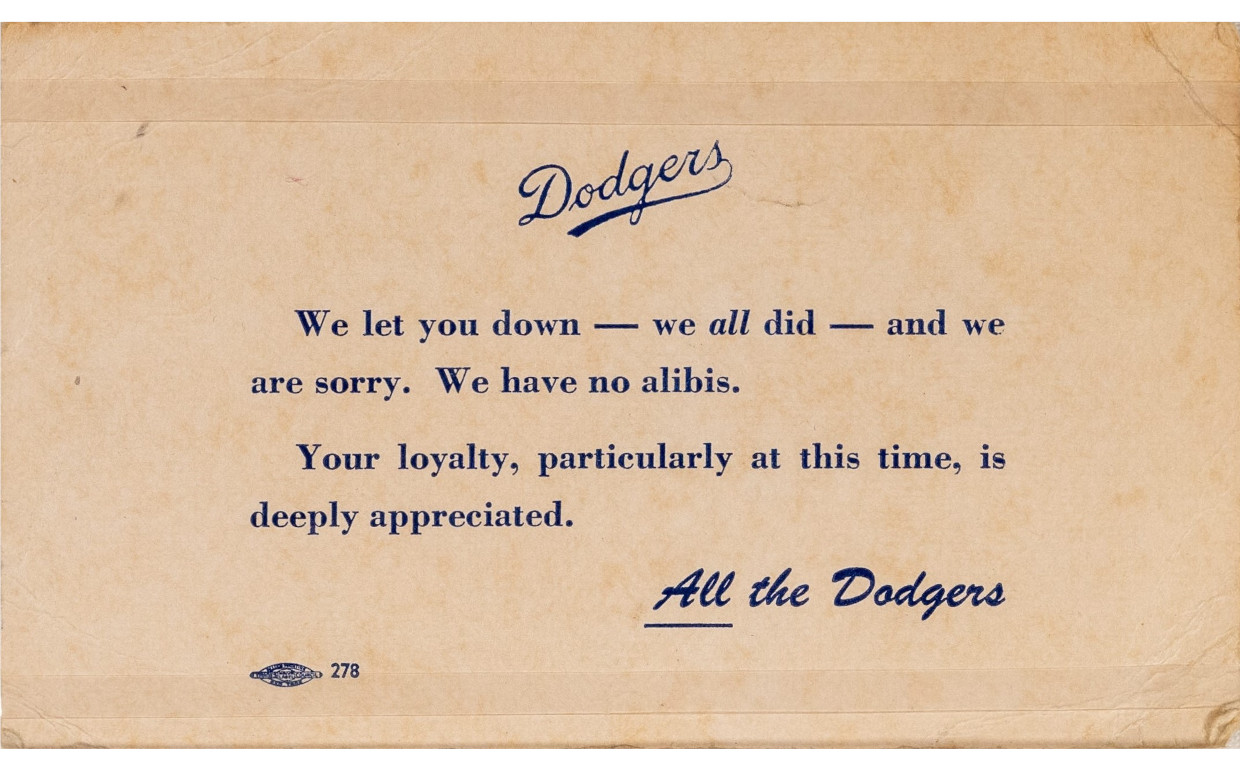

Dodgers season ticket holders were sent this unusual apology card shortly after the loss to the giants. walteromalley.com

Unsurprisingly, Branca continued to field questions about the fateful pitch for the rest of his life. When he did so, however, he often spoke candidly about the role Robinson played that afternoon in the clubhouse and the bonds that they forged over their careers. As fans continued to celebrate both Robinson and the Dodgers in the decades after the team left for Los Angeles, Branca focused on the importance of being a good teammate even under the most trying conditions. The Shot Heard ‘Round the World is a story of heartbreak still wistfully recalled by a generation of fans who remember the golden age of New York baseball. But for its participants, it was a moment of solidarity and friendship that Branca preserved and passed down through generations alongside the story of the Dodgers’ crushing defeat.

References

- Joe Trimble, “Dodgers ‘No Quitters’; Defense Saved Day,” New York Daily News (New York), October 1, 1951.

- Carl Rowan and Jackie Robinson, Wait Till Next Year (Random House, 1960), 221-222

- Rud Rennie, “Greatest Home Run I Ever Hit, Says Robinson After Victory,” New York Herald Tribune, October 1, 1951.

- Courtesy of Major League Baseball

- James Elfers, “Focus on the Giants’ Cheating Scandal of 1951 – Society for American Baseball Research,” Society for American Baseball Research, n.d., accessed August 25, 2025, https://sabr.org/journal/article/focus-on-the-giants-cheating-scandal-of-1951/.

- Bill Madden, “Relieving Branca’s Pain,” New York Daily News (New York), April 16, 1997.

At the end of 1954, Jackie and Rachel Robinson, along with their three children, left their home in St. Albans, Queens for a new property in Stamford, Connecticut, a suburb located about an hour north of New York City. For Jackie Jr., age 7; Sharon, age 4; and David, age 2, this was a major transition. In Stamford, the Robinson kids found themselves in a wholly different environment. They were almost universally the only Black students in their classes, and the task of desegregation weighed heavily on their young shoulders. As the changes brought on by the Civil Rights Movement unfolded across the United States, the Robinsons began to understand that their stories, too, were microcosms of a broader national transformation.

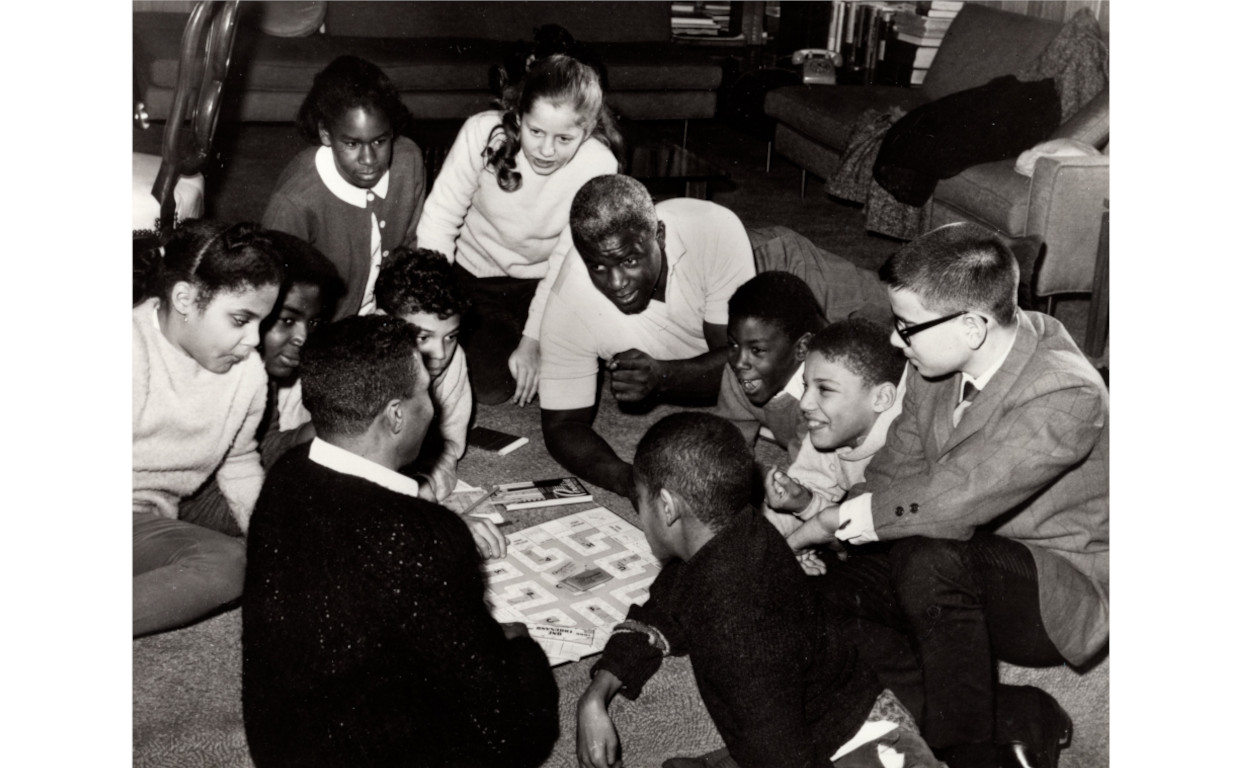

Jackie Robinson playing a board game with Jackie Jr., David, Sharon, and their neighbors in Stamford, CT, date unknown. Jackie Robinson Museum

Jackie Jr. began school at Martha Hoyt Elementary soon after the move. The Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court decision, making segregation in schools illegal, had been handed down earlier that year in May 1954. Though Stamford schools were not legally segregated to begin with, the exclusivity of the community rendered Hoyt an all-white environment. As Rachel and Jackie Jr. walked towards the doors of the school on the first day, other parents whispered and stared at the unexpected sight of a Black student enrolling. Despite this response, Rachel remembered being mostly welcomed and supported in the early days of her move.1

Inside the school, the difficulties were more apparent. Writing in her memoir years later, Sharon recounted how Jackie was ignored academically, even from an early age, by most of his teachers.2 This neglect had an effect on his sense of self-worth, too. At one point, ashamed of his ancestry, Jackie began to refer to himself as Puerto Rican to his classmates.3 Being placed into such an environment at an early age made it difficult to cultivate the same type of racial pride that their father used to stand up the abuse and insults he received in baseball years earlier. In response, Rachel said, the Robinsons began to purchase books with multiracial themes to help build the kids’ confidence in their own identities in a desegregating environment.

David Robinson (second row, fourth from left) with his graduating class at New Caanan Country Day School, date unknown. David primarily attended local private schools in the Northeast, first in Connecticut and then in Massachusetts. Reflecting on his experiences, David remarked on how an overt moment of racial harassment helped galvanize the support of his closest friends during his time in school. Jackie Robinson Museum

The school system itself was not the only difficulty. In addition, the children faced racist mistreatment from their peers. These issues compounded as they grew older and formed friendships across racial lines, which were often fraught. “It became difficult when we became teenagers,” Sharon later recounted in a Jackie Robinson Museum interview.4 “Black and white kids…didn’t socialize together. There was a natural breaking-off point when you entered your teenage years.” Sharon remembered how at the time, she resented her parents for raising them in what was essentially an all-white community.5

Notably, Jackie and Rachel did not view themselves or their children as crusaders in the fight for equality. They did not move to Connecticut to stir up trouble about housing discrimination, as was alleged in the press.6 Nor did they believe that raising their children in Connecticut was purely a character-building experience. They faced the same choices that many middle-class Black families faced at the dawn of desegregation: whether to move their children and subject them to mistreatment at a better-resourced school in a wealthier, whiter community, or stay put and experience the structural racism of underinvestment in a school that was almost entirely Black.

Jackie, Rachel, and the family around their dinner table, ca. 1957. Jackie Robinson Museum

Home became a place for discussions about integration that were often just as personal as they were political. It was around the table where Jackie told his children about his calls with civil rights leaders and organizers, including the Little Rock Nine, a group of Black high school students who fought to desegregate Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas in 1957. Orville Faubus, then the governor of Arkansas, mobilized the National Guard for a days-long standoff as he fought to prevent the desegregation of Little Rock’s schools. Like millions of Americans, the Robinson kids watched the crisis unfold on television, as hundreds of white protestors gathered to prevent the students from enrolling. No state troopers blocked the doors of the Robinsons’ elementary schools, and the tree-lined streets of suburban Connecticut were a long way both literally and figuratively from the battle lines of Arkansas. Even so, their experiences revealed the importance of school desegregation to the fight for racial equality in America.

Pro-segregation protestors gather outside the State Capitol in Little Rock, Arkansas, 1959. Two years earlier, nine Black students attempting to enroll at Central High School were greeted by a similar mob. Wikimedia Commons.

As Jackie Jr., Sharon, and David grew older, the fight for desegregation in education continued, and the three children were looking for a way to add their voices to the growing chorus. In 1963, the Robinson family traveled south to participate in the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. After years of discussing the unfolding movement at home, the three Robinson children were able to join in, clapping and singing as hundreds of thousands of marchers gathered to fight for equality and listen to the words of the architects of the movement. Writing in his weekly column in the New York Amsterdam News, Jackie focused on the experiences of his children, describing Jackie Jr.’s excitement for the movement and David’s brief interview with a reporter.7 To Jackie, this march was an opportunity to share his civil rights work with the children who, up to that point, had only experienced it through the television and through their father’s stories.

David, Jackie, and Daisy Bates march together at the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom in 1963. Getty Images

After the march, the Robinsons returned to Stamford invigorated and with a sustained sense of purpose. Over the years, their home became a place for civil rights jazz fundraisers, meetings with prominent politicians, and gatherings with friends new and old. But the difficult memories of integration were not lessened by developments. Later on, Jackie wrote candidly about the issues his children faced. “We now realize how much being the only black can hurt,” he noted, reflecting on the weight of their struggles.8 “A good school involves much more than excellent teaching.” Even in the face of these challenges, the Robinsons were able to learn and grow amidst the tumult of change. The stories shared around the table and the joy of the marches offered the chance for the Robinson children to see that they were not alone in a changing America. More than anything else, they revealed how the nationwide struggle for desegregation was most acutely felt by the children who carried the burdens of being the “first,” just like Jackie himself.

References

- Carl Rowan and Jackie Robinson, Wait Till Next Year (Random House, 1960), 314-315

- Sharon Robinson, Stealing Home : An Intimate Family Portrait by the Daughter of Jackie Robinson (New York, NY : HarperCollins, 1996), 92

- Jack Herrison Pollack, “Meet a Family Named Robinson,” Parents, October 1955.

- “Jackie Robinson Museum Interview of David and Sharon Robinson.”

- Sharon Robinson, Stealing Home : An Intimate Family Portrait by the Daughter of Jackie Robinson (HarperCollins, 1996), 67

- Arnold Rampersad, Jackie Robinson: A Biography (Knopf, 1997), 273

- Jackie Robinson, “Marvelous March,” New York Amsterdam News, September 7, 1963

- Jackie Robinson and Alfred Duckett, I Never Had it Made (Putnam, 1972), 120

Jackie Robinson’s skill on the baseball diamond rarely went unnoticed. No matter where he and the Dodgers traveled, fans of all backgrounds filled stadiums to witness one of the era’s most electrifying players. Between 1949 and 1954, representing the Dodgers and the National League, Robinson earned six consecutive selections to Major League Baseball’s All-Star Game — a testament not only to his exceptional skill, but also to the impact he had on the sport at large.

Robinson’s stats in the Midsummer Classic were remarkable. Across 18 plate appearances, Robinson recorded a .333 batting average against the top pitching of his era, including two doubles and a home run. But more than just numbers, his effective play demonstrated to fans across the country and the world what many already knew: Black players were not only equal in skill to their white counterparts, but they were also stars.

1945: A Star on the Monarchs

It is important to remember that the 1949 edition was not Jackie’s first All-Star Game. In 1945, while wearing a uniform for the Kansas City Monarchs, Robinson took the field at the East-West game, an annual tradition dating back to 1933, the same year the white major leagues’ All-Star Game was inaugurated. Over 30,000 fans packed into Chicago’s Comiskey Park to see a constellation of top players in the Negro Leagues, including Robinson, Quincy Trouppe, Buck Leonard, and future Dodger catcher Roy Campanella.

Robinson was the starting shortstop for the West. Although he went hitless in five at-bats, it didn’t matter. The West jumped to an 8–0 lead by the third inning, and the game ended with Robinson making a stellar play at shortstop to secure the victory. Just weeks later, his historic journey to the major leagues began when Dodgers scout Clyde Sukeforth came calling.

Negro Leaguers line up for a photo at the 1936 East-West Game at Comiskey Park in Chicago. These games, which showcased the best of the Negro Leagues, continued until 1962. Wikimedia Commons

1949: Breaking Barriers

Though he had an impressive rookie season in 1947 with the Brooklyn Dodgers, and an even better 1948, Jackie Robinson’s first MLB All-Star Game was not until 1949. Fittingly enough, the game was held at Brooklyn’s Ebbets Field. Robinson was joined on the National League squad by his barrier-breaking Dodgers teammates Don Newcombe and Roy Campanella. Larry Doby, the first Black player in the American League, represented the Cleveland Indians in the other dugout. Together, the four players integrated the All-Star Game.

Chaos on the field quickly overshadowed the momentous occasion. The game was a slugfest, with the American League carrying the day by a score of 11 to 7. The National League committed five errors (including one each by Dodgers Pee Wee Reese and Roy Campanella), setting a record for most errors in an All-Star Game by a single team that remains unbroken. Robinson, for his part, was flawless. He played a perfect nine innings at second base and made his mark at the plate.

In his first at-bat, he doubled to left off of the Red Sox’ Mel Parnell and came around to score on Stan Musial’s home run. In his next time at the plate, he drew a walk. When Musial followed with a single to left, Robinson showed off his blazing speed by dashing to third and scoring on Ralph Kiner’s double play soon after.

Though the AL won the game, Robinson was content. Speaking to a reporter after the game, he noted that the quality of play was not top-notch, but being in the game was nonetheless a thrill.

(left to right) Roy Campanella, Larry Doby, Don Newcombe, and Jackie Robinson pose for a photograph at the 1949 All-Star Game. Associated Press

1950 – 1951: Finding his Groove

If the previous year’s game was a slugfest, 1950’s was a slog. This time, the National League managed to outlast their counterparts over a 14-inning, 4–3 contest. Robinson, as usual, provided the first spark. Facing the Yankees’ Vic Raschi, Jackie lashed a single to right and scored on Enos Slaughter’s triple a batter later. It would be Robinson’s only hit in the game; he flew out three times before being lifted for a pinch hitter in the 11th.

In 1951, Robinson’s performance was even stronger. In the sixth inning, Robinson drew a walk and promptly scored after teammate Gil Hodges homered to left. His next at-bat in the seventh, however, was quintessential Robinson. With runners on the corners, Robinson waited for the Tigers’ Fred Hutchinson’s delivery and dropped a perfect bunt down the third-base line, scoring Richie Ashburn and giving the National League a 7-3 lead. Robinson would add another hit to his total in the top of the ninth as the team sealed their second victory in a row.

These were not just All-Star appearances. They were clinics on how to influence a ballgame.

Jackie was awarded this cigar box when he was selected to participate in the 1951 All-Star Game. This sterling silver box is engraved with the name of Ford C. Frick, then the president of the National League. Jackie Robinson Museum

1952: It’s Outta Here!

The 1952 contest was, by all accounts, soaked by a night of rain and nearly unplayable. But if the field was muddy, Robinson’s swing was crisp. Again, facing Vic Raschi, Jackie stepped to the plate with one down and none on in the top of the first. He smashed Raschi’s first pitch into the upper deck of Shibe’s left-field stands, giving the Dodgers a 1–0 lead.

Three innings later, the Cubs’ Hank Sauer joined in the fun, hitting another home run to give the National League a 3–2 lead. That would be the rest of the scoring that afternoon. During the fourth inning, the rain returned with a vengeance, inundating the players and fans for another frame. By the end of the fifth, the umpires called the game, leaving the National League with another victory. Despite his heroics, Robinson was nonchalant about the result of the game. Not even a home run could prevent Jackie and his competitive spirit from fixating on a misplay he made on a muddy grounder in the fourth inning. “Well, we won, and that’s the main thing,” Robinson said to Dick Young, a New York Daily News reporter with whom he had often clashed. “But I should have had that ball.”

A program for the 1952 All-Star Game. Jackie Robinson Museum

1953 – 1954: Still on Top

Robinson returned for the 1953 All-Star Game at Cincinnati’s Crosley Field, for the first time as a reserve. The 1953 Dodgers, well on their way to being one of the most dangerous lineups of all time, sent six position players to Cincinnati’s Crosley Field. Robinson entered the game as a pinch hitter in the sixth and popped out. It wasn’t his night, but the National League still won a 5–1 victory.

In 1954, Robinson again returned for his final All-Star Game, this time as a starter. Though the National League lost, Robinson continued his excellent All-Star Play. He started slowly: in the third inning, against the Yankees’ indomitable Whitey Ford, Robinson grounded out. By the next time he came to the plate, Ford had been lifted for Sandy Consuegra, and the National Leaguers had found themselves in a 4–2 hole thanks to an Al Rosen homer the inning before. With runners on first and second, Robinson doubled to right-center, tying the game at four runs apiece.

In the fourth inning, Jackie Robinson was lifted in a defensive substitution for none other than Willie Mays, the face of the next generation of Black superstars. Mays would go on to win both the National League MVP and the World Series with the New York Giants that year. Jackie Robinson, 35 years old and in his eighth season, quite literally made way for Mays to shine on baseball’s biggest stage, and the “Say Hey Kid” did not disappoint. In the eighth inning, Mays singled and scored on Gus Bell’s home run. It would not be enough. After a back-and-forth contest, the American League won 11 to 9.

Jackie Robinson’s profile in the 1955 Brooklyn Dodgers yearbook. Despite slowing down in 1954, Robinson’s performance at the plate and in the field was more than enough to earn him a spot as the National League’s starting left fielder. Jackie Robinson Museum

A Legacy of Excellence

Across six MLB All-Star Games and one Negro American League’s East-West Game, Jackie Robinson compiled an impressive resume against the top talent in baseball. He and the National League won four out of the six of the games he played, and he recorded a hit in every game in which he was a starter. Jackie Robinson’s All-Star performances helped guarantee his legacy as a top-notch performer on one of the biggest stages in the game. These are major milestones, not just for a ball player, but for a sport, a nation, and a movement.

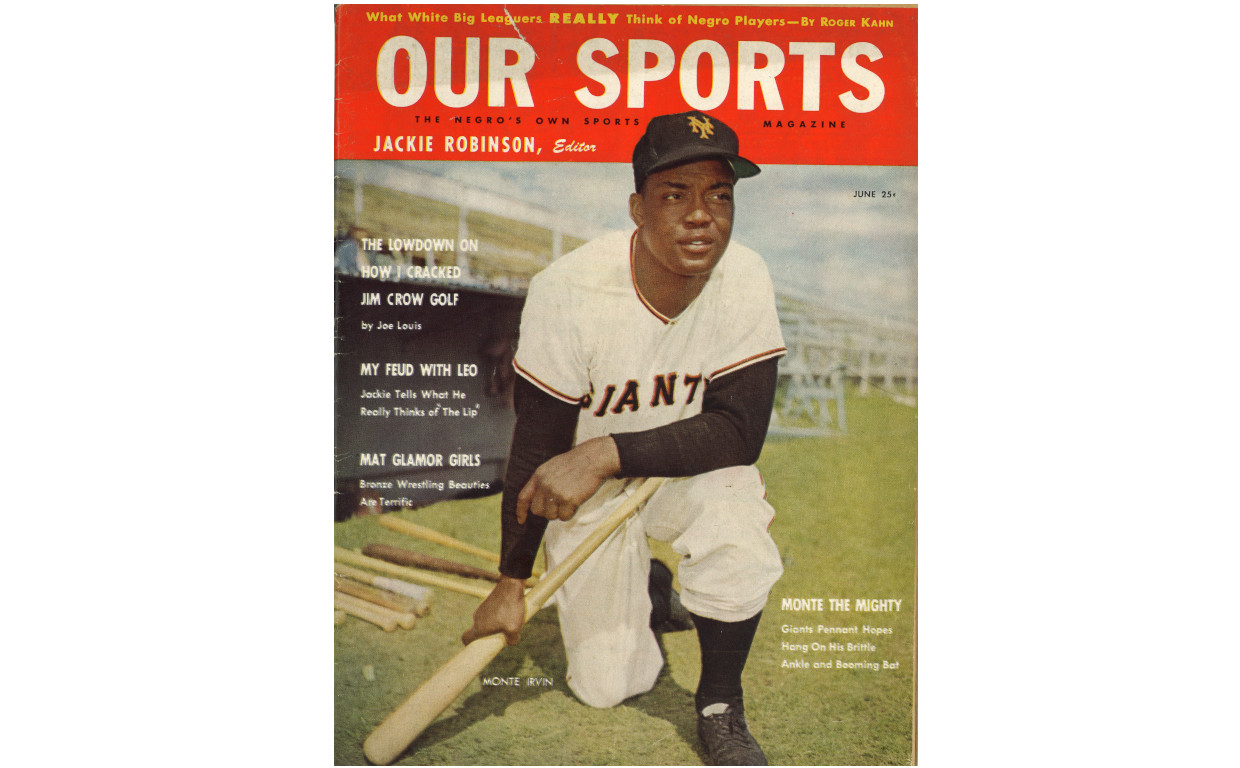

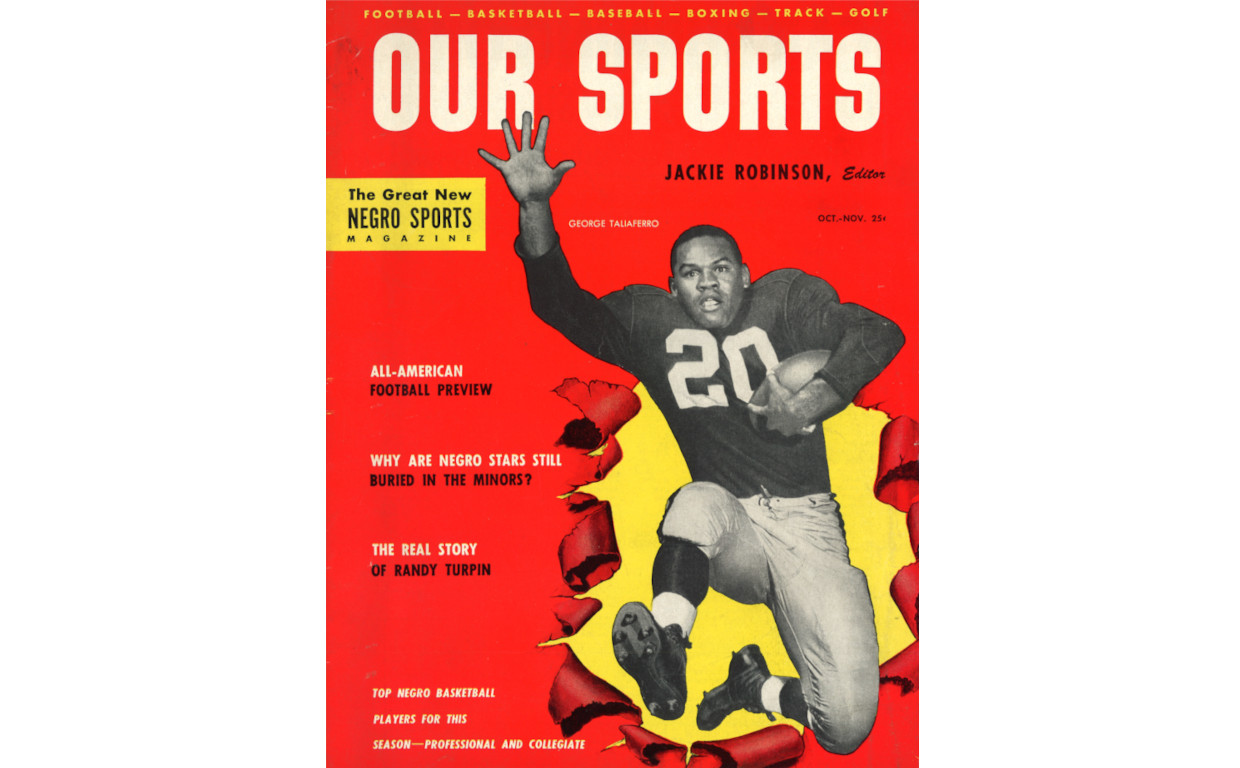

In the spring of 1953, Our Sports, a new and ambitious sports magazine hit the shelves at newsstands around the country. It bore a famous name at the top of the masthead: Jackie Robinson. Writers explored the world of Black sports as they saw it, penning entries on a diverse range of athletes who often went unheralded in the white press. Robinson himself contributed articles on the state of race in baseball. Though the magazine was short-lived, it offered an opportunity for writers to approach issues of race and sports culture through a critical lens. The questions that the magazine raised about how Black athletes are depicted in the media continue to resonate with sports fans today.

June 1953 issue of Our Sports, Jackie Robinson Museum

In February 1953, when news broke in the Pittsburgh Courier that Jackie was tapped as the editor of a new sports magazine, he was just getting ready for his seventh season with the Brooklyn Dodgers and would have little time for journalistic or literary affairs.1 Naturally, the busy Robinson was not the only editor. He was joined by S.W. Garlington, a former New York Amsterdam News columnist and Morehouse alumnus, as executive editor. Jackie, as usual, was more than a famous name. As the first issue went to print, other news sources assured readers that Robinson would “personally pass” on all of the publication’s articles.2 Roger Kahn, who received a hefty commission to write as Jackie, brought flavor to the magazine’s reporting.3 Other notable contributors included Wendell Smith, the Pittsburgh Courier journalist who helped Robinson desegregate baseball, and heavyweight champ Joe Louis, who wrote not about his boxing career but his attempts to desegregate the game of golf.4

Our Sports arrived at a critical time in the history of American sports media. The appetite for photojournalism and newsmagazines was growing rapidly, and sports fans were a particularly profitable constituency. Sport Magazine, launched in 1946, featured color photos of athletes across a wide range of disciplines, bringing images of athletes themselves into readers’ homes on a large scale. Sports Illustrated would publish its first issue in 1954, establishing a durable media empire. A wide range of smaller magazines offered up features and action shots for subscribers as well.

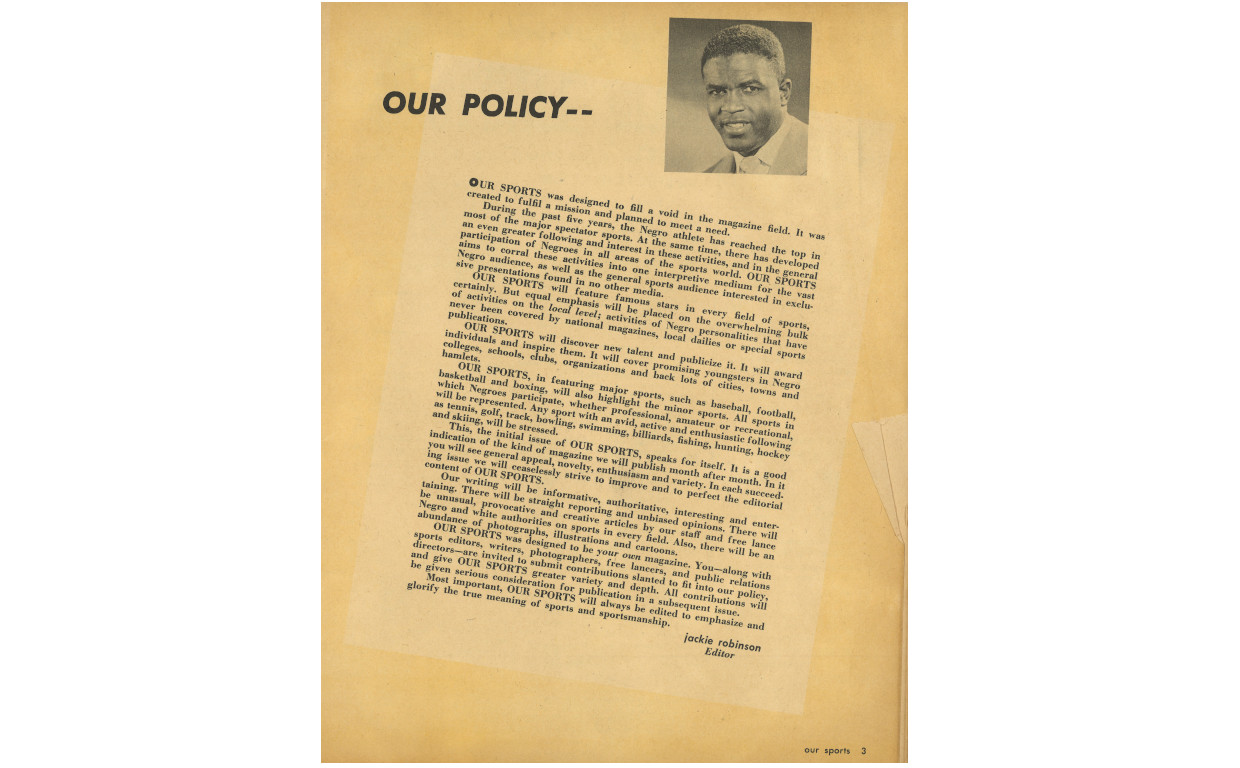

Opening statement of Our Sports, May 1953, Jackie Robinson Museum

The time was ripe for a new publication that was capable of responding both to a growing desire for sports magazines and Black fans’ desire for serious discussions of race and sports. Robinson himself frequently bemoaned both the apathy and mistreatment Black athletes often faced at the hands of the white press. Black athletes were gaining prominence across the entire athletic landscape, including, as the magazine would show, in sports that were slower to integrate than baseball. Robinson said as much on the first page of the inaugural issue: “Our Sports was designed to fill a void in the magazine field,”5 he triumphantly declared. “Over the past five years, the Negro athlete has reached the top in most of the major spectator sports…Our Sports aims to corral these activities into one interpretive medium for the vast Negro audience.”

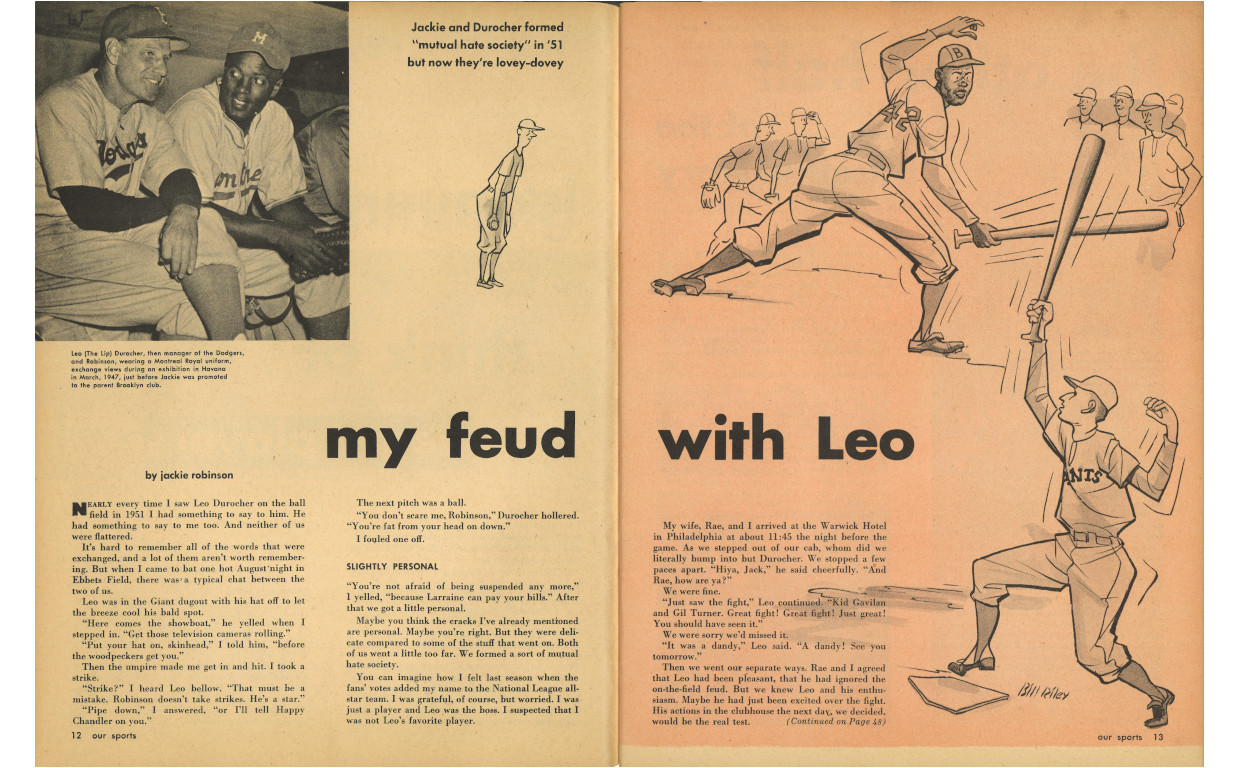

“My feud with Leo” by Jackie Robinson, from the June 1953 issue of Our Sports, Jackie Robinson Museum

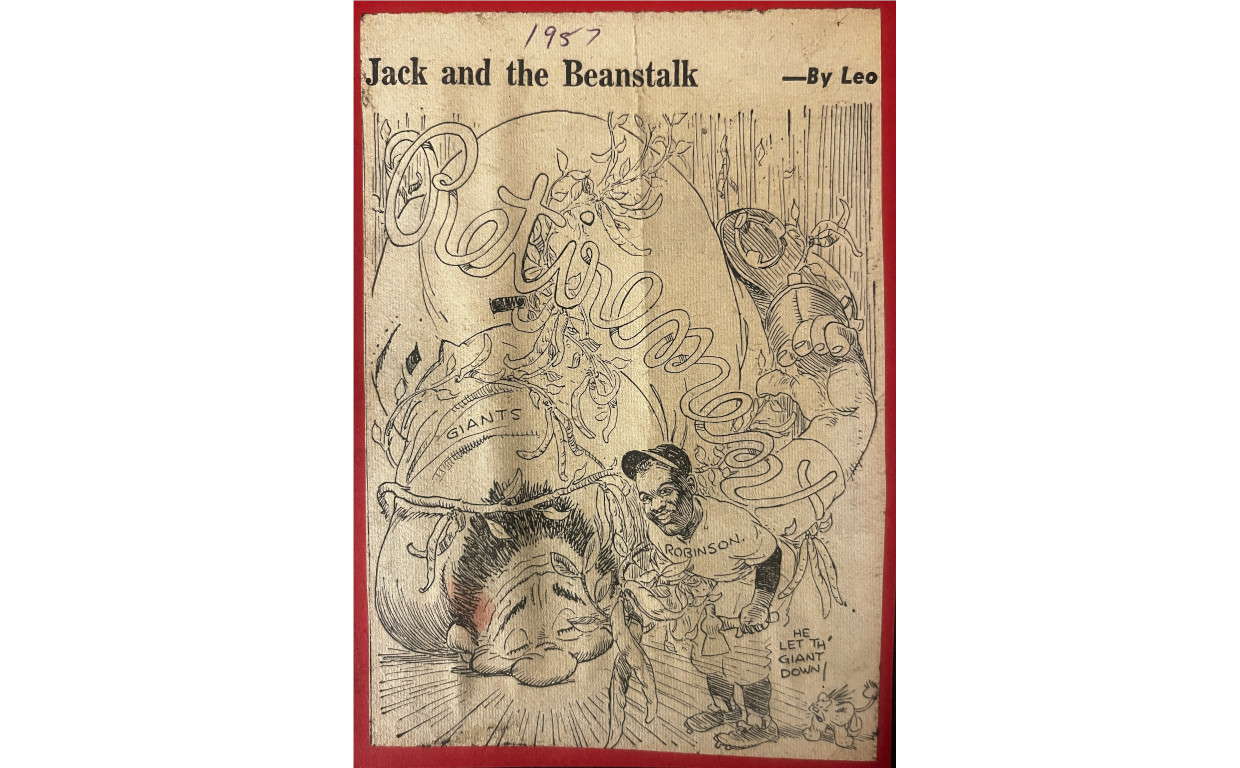

At the beginning of most issues, baseball took center stage. Features in Our Sports discussed the chances of the New York Giants during the 1953 campaign, as well as Jackie’s long-running feud with their manager, Leo Durocher. Others examined players’ MVP chances or the interests of their wives. In May, Robinson (complete with a cartoon depicting him as a fortune-teller!) offered his predictions on the 1953 National League season.

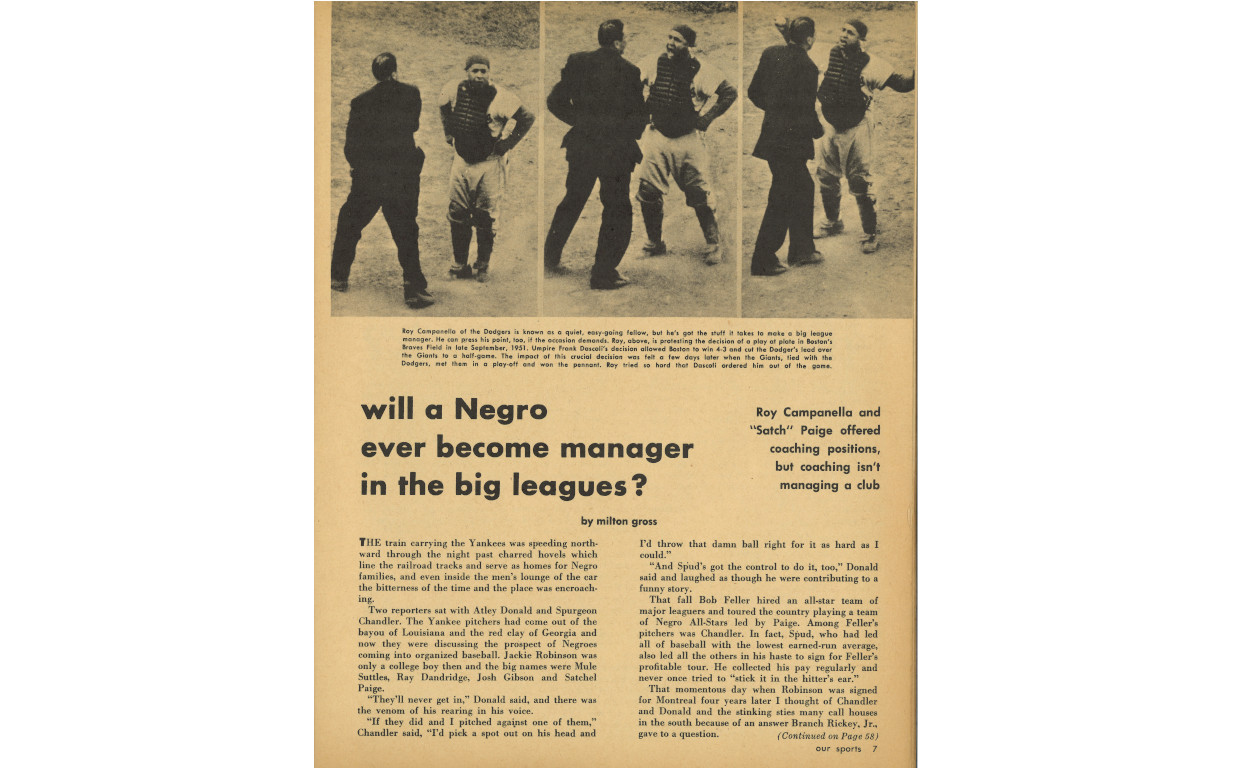

“Will a Negro ever become manager in the big leagues?” by Milton Gross, from May 1953 issue of Our Sports, Jackie Robinson Museum

The first article in that year’s May issue, by New York Post veteran Milton Gross, pointedly asked whether or not there would be a Black manager in the major leagues. This was a key concern for Robinson. He frequently spoke about the need to diversify the upper echelons of baseball and was disappointed when he received no offers to coach after he retired from the game. Gross, who had previously written articles defending Robinson from his many detractors, began his piece with a fiery condemnation of two racist Yankees pitchers who believed, in the 1930s, that the game of baseball would never be integrated. He listed a number of potential managerial candidates while arguing against popular adages that while players would never listen to a Black skipper. “Men play for their salaries,” Gross affirmed. “And they’d play again, even under a Negro manager.”6 The article was published at a time when no Black player had been in the major leagues longer than six seasons. To much of the sports-writing establishment, the subject of Black managers was practically unthinkable. But Gross, Robinson, and the other editors knew that they had a platform to push the envelope. Neither Robinson nor Gross would live to see the first Black manager, Frank Robinson, who did not take the field until 1975 with Cleveland.

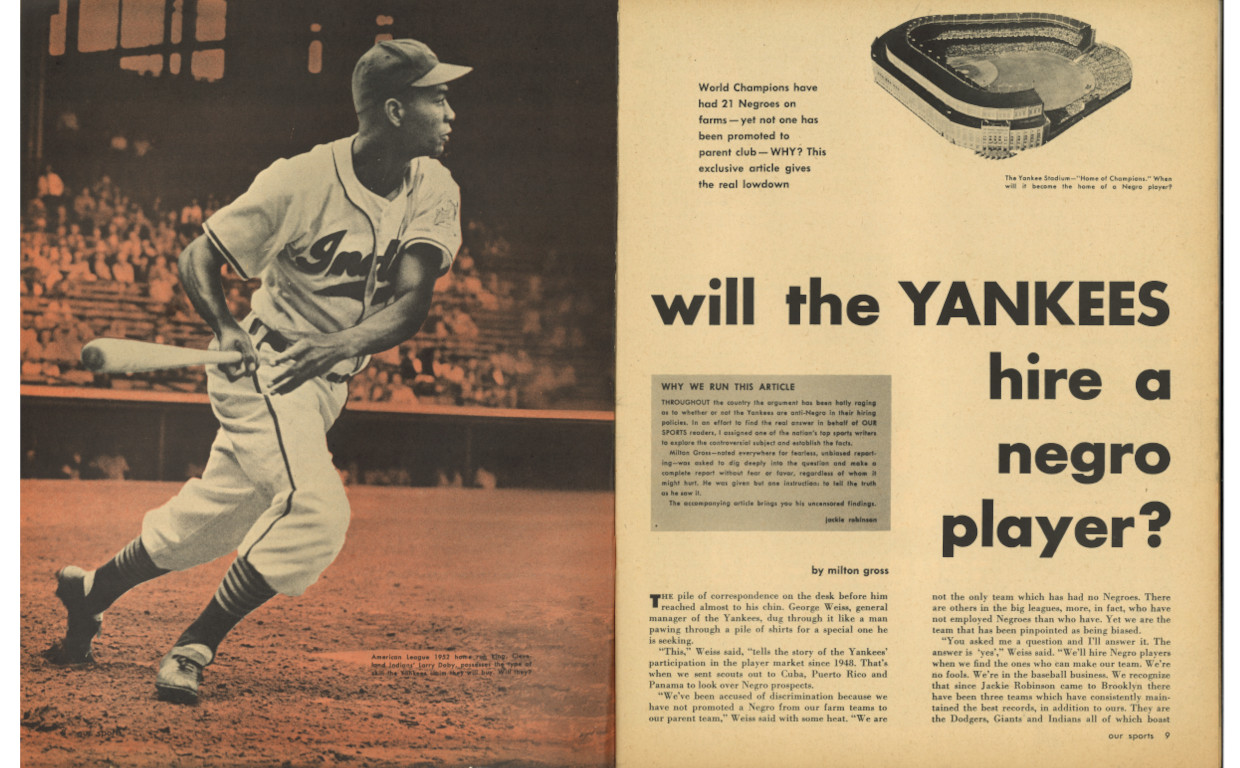

“Will the Yankees hire a negro player?” by Milton Gross, from June 1953 issue of Our Sports, Jackie Robinson Museum

Our Sports also weighed in on other issues close to Robinson. In November 1952, Jackie stirred up controversy after he stated on a television program that the Yankees management was discriminatory towards Black players.7 Indeed, by 1953, the Yankees were one of a handful of teams yet to sign a Black ball player to their major league squad.

In the July issue of Our Sports, Milton Gross tackled the question, examining the Black players in the Bombers’ extensive farm system, including Vic Power and Elston Howard.8 Though he stopped short of making a conclusion (and was sure to highlight vile statements made by the team’s press secretary), Gross certainly painted a rosier picture than the one offered by his editor on television eight months before. Perhaps not unexpectedly, another article appeared in the final issue bemoaning the reality that many skilled Black players spend too much time languishing in the minor leagues.9

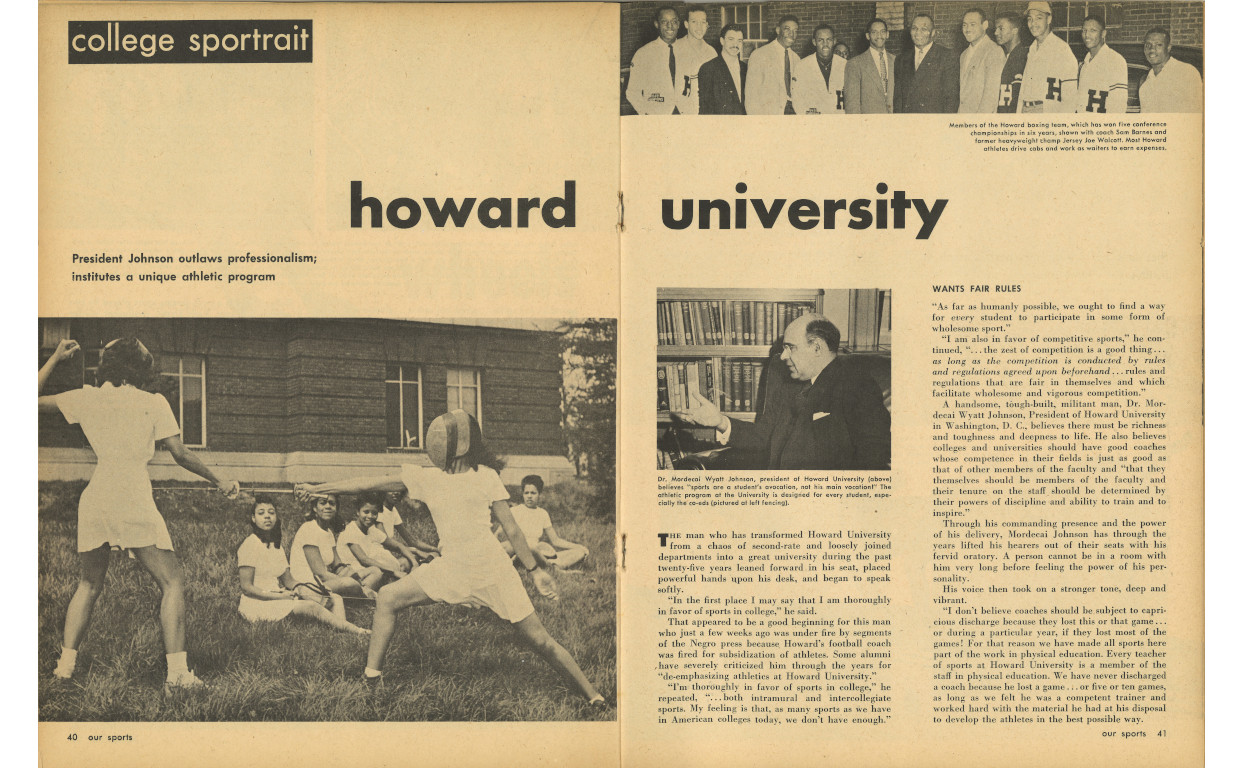

“College Sportrait: Howard University,” from June 1953 issue of Our Sports, Jackie Robinson Museum

Remarkably, baseball was just a sliver of the magazine’s output. Entries about Black sport hunters, bowlers, jockeys, and golfers appeared alongside the biggest names in team sports. It also provided a stage to celebrate the successes of Black universities’ athletic squads. Robinson, a four-sport athlete at UCLA, understood the importance of college athletics not just for the development of professionals, but for the fact that collegiate athletic circuits remained one of the successes of desegregation in American culture thus far.

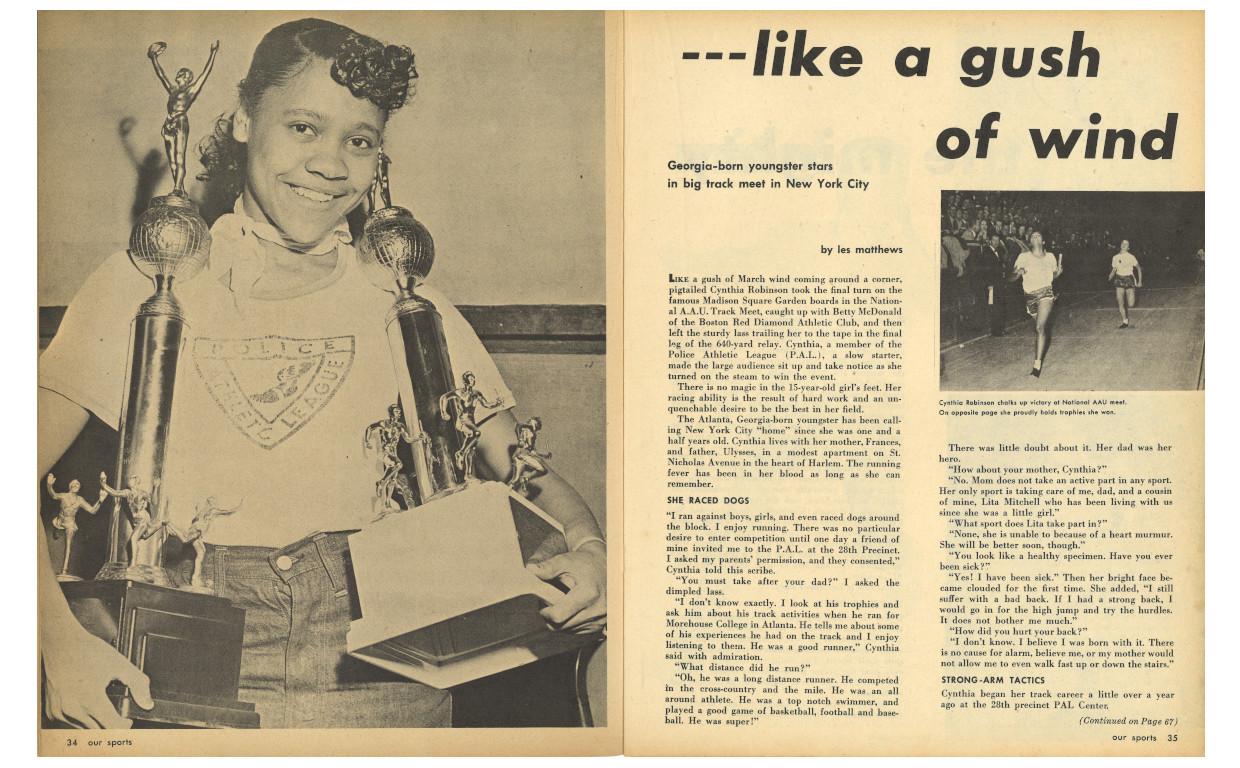

“…like a gush of wind” by Les Matthews, from the May 1953 issue of Our Sports, Jackie Robinson Museum

Equally notable is the magazine’s focus on Black women athletes. As scholar Amira Rose Davis has described, many portrayals of Black women in sports at the time focused heavily on the femininity of the athletes and little on their talent.10 Our Sports resisted this paradigm, depicting the athletes in their athletic gear and highlighting their victories. Again, Robinson and the editors highlighted HBCU athletes and those who were making strides for desegregation in “country club sports” such as tennis and golf. Althea Gibson, whom Our Sports profiled in the June issue, became a frequent collaborator with Robinson, playing as a duo in celebrity golf tournaments in the 1960s.

The balance between celebration and social struggle was key to the magazine’s output. Like many Black magazines and newspapers of its era, Our Sports worked to both catalyze readers’ interest in the ongoing fight for equality while finding joy in the everyday lives of Black Americans. In many articles, athletes’ encounters with Jim Crow, their struggles to desegregate their field, and their relationships with white teammates and opponents were recounted in close detail. But frequently, the authors and editors instead focused on the skill and successes of the players themselves, allowing them to be celebrated not just as pioneering Black athletes, but as equal participants whose batting averages, personal bests, and handicaps counted just as much as anyone else’s—and merited equal celebration and attention from the media.

October-November 1953 issue of Our Sports, Jackie Robinson Museum

It was an ambitious project, though sadly, not a durable one. Our Sports only lasted for five issues. After publishing monthly from May to August 1953, the magazine was able to put out an October-November issue later that year before disappearing entirely. Black publications, especially magazines, often operated on shoestring budgets. Our Sports was unable to attract the major advertisers that helped bankroll white publications and was unable to last beyond the baseball season.11

The end of Our Sports did not mark the end of Robinson’s journalistic career. After retiring from baseball, Robinson became a prolific weekly columnist, first with the New York Post in 1959 and later with the New York Amsterdam News through most of the 1960s. There, he continued to write about sports, fighting back against segregation at the New York Athletic Club and writing in support of a threatened boycott of the 1968 Mexico City Olympics. The stories on its pages helped build a world of Black sports at the moment the Jim Crow establishment was falling. The editors and writers knew there was a lot to celebrate—and even more work to be done.

References

- Izzy Rowe, “Izzy Rowe’s NOTEBOOK: Sons and Daughters of Harlem, USA,” Pittsburgh Courier, February 14, 1953.

- Marion Jackson, “Sports of the World,” Atlanta Daily World, May 31, 1953; “Jackie Robinson Edits First All-Negro

Sports Magazine,” Atlanta Daily World, April 29, 1953. - Kahn briefly discusses his experiences as a writer in his 2014 book, Rickey and Robinson.

- Joe Louis, “My Toughest Fight,” Our Sports, June 1953, Jackie Robinson Museum.

- Jackie Robinson, “Our Policy,” Our Sports, May 1953, Jackie Robinson Museum.

- Milton Gross, “Will a Negro Ever Become a Manager in the Big Leagues?,” Our Sports, May 1953, Jackie Robinson

Museum. - Arnold Rampersad, Jackie Robinson: A Biography (New York: Knopf, 1997), 253.

- Milton Gross, “Will the Yankees Hire a Negro Player?,” Our Sports, June 1953.

- Larry Marthey, “Why Do Negro Stars Get Buried in the Minors?,” Our Sports, November 1953.

- Amira Rose Davis, “Supporting Black Women Athletes,” in 42 Today: Jackie Robinson and His Legacy (New York,

2021), 177–88. - Mark Weinstein, “Breaking Barriers,” Athletes Quarterly, accessed May 21, 2025,

https://athletesquarterly.com/athletes/rickeyandrobinson.

In the early 1960s, both Jackie Robinson and Malcolm X were towering figures in the struggle for racial justice in the United States. Though they were both active in Harlem during a time of tumult and political upheaval, they drew their support from different constituencies and often had sharply contrasting views on how the unfolding movement(s) should proceed. Though they met in person only briefly in 1962, they traded barbs and disagreements in newspaper columns, debating the stakes of the movement openly and in public. Robinson accused Malcolm of attention-seeking and poor leadership, while Malcolm criticized Robinson’s associations with white moderates who were often unresponsive or hostile to the demands of Black communities in cities across the country. Even so, the two were more aligned than either readily admitted. After Malcolm’s assassination in early 1965, Jackie wrote that the pair largely agreed on the severity of the issues facing Black Americans, even if their tactics diverged.

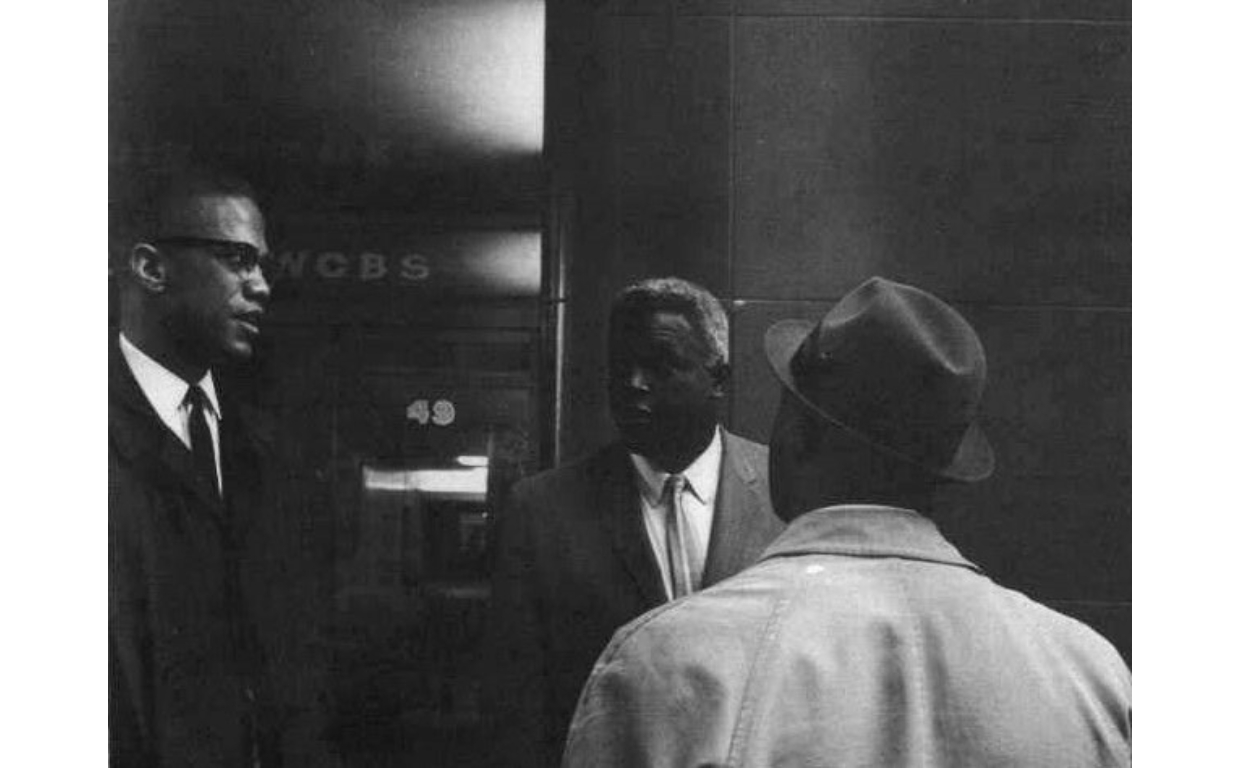

Malcolm X and Jackie Robinson at WWRL studios, July 1962. The New York Public Library

Malcolm, like Jackie, grew up far afield from the streets of Harlem. Born in Omaha, Nebraska in 1925, he moved with his family to Milwaukee, Wisconsin, and then to Lansing, Michigan, while still a young boy. Malcolm’s parents, Earl and Louise Little, were hardworking and part of Marcus Garvey’s Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA). In 1930, after being forced out of the home they purchased in a white neighborhood in Lansing due to local segregation laws and sentiments, Malcolm’s parents bought a home outside of the city. Malcolm’s family continued to have frequent run-ins with local white supremacists, who deemed Malcolm’s father “uppity” and were believed to have been behind Earl Little’s early death in 1931, which was reported as a “streetcar accident.”

The challenges brought on by the death of Malcolm’s father likely led to Malcolm’s trouble with law enforcement. After being imprisoned in Boston on a burglary charge, Malcolm began his conversion to Islam. In 1952, he met Elijah Muhammad, the leader of the Nation of Islam, and began to establish new mosques across the United States, traveling thousands of miles to speak to congregations interested in the Nation of Islam’s teachings. As he did so, he brought a militant message to thousands of Black Americans who were growing cynical about desegregation and Christianity more broadly. As the Civil Rights Movement accelerated, especially in the South, Malcolm and his followers remained skeptical of the usefulness of working toward desegregation, instead developing a Black nationalist practice of self-reliance and self-defense tailored to the urban problems that many Nation of Islam members faced.

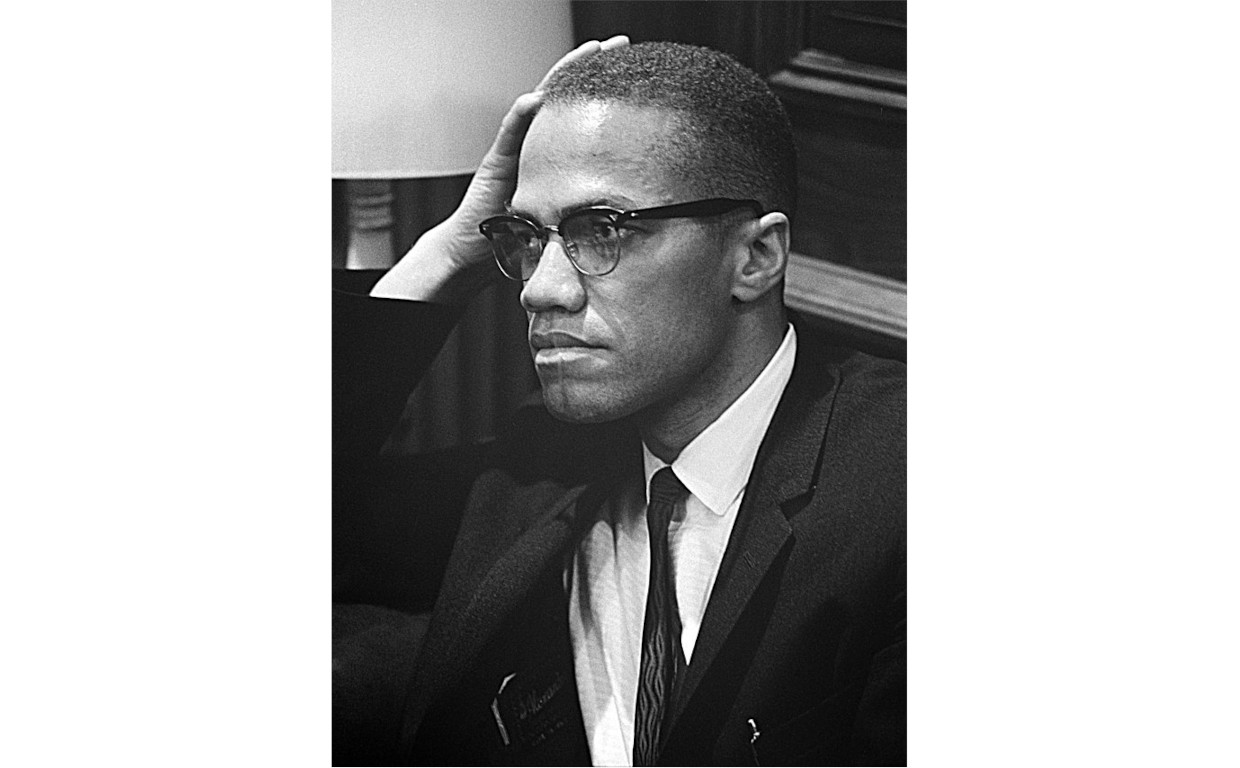

Malcolm X in 1964. Wikimedia Commons

In many ways, Robinson and Malcolm could not have been more different. Although both grew up in poverty, Robinson’s life and career in sports were marked by early successes in desegregation, through which Robinson was able to earn the acceptance (often begrudging) of at least some segments of white America. Malcolm, who was harassed by welfare officials, social workers, and the carceral state for much of his early life, acutely saw the limits of integration into a system that spared little dignity for Black people. As both influencers’ statures grew, they carved out different niches for themselves that were shaped by their personal experiences with race and injustice.

Malcolm X speaks in front of Harlem’s Hotel Theresa in 1963. United Press International

Robinson and Malcolm X first met in 1962, following a heated debate between Jackie and Lewis Michaux, a Black nationalist and bookstore owner in Harlem. What was ostensibly a protest against a new, white-owned steakhouse undercutting a nearby Black business had developed into an ugly series of pickets, with protesters chanting antisemitic slogans against the owners of the new restaurant. In his weekly column in the New York Amsterdam News, Robinson excoriated the protestors, who were supporters of Michaux, advising them not to use bigoted language.1 Robinson engaged Michaux in a heated radio debate after which Michaux compelled the protestors to back off. Malcolm X, himself not a participant, was present at the studio where the debate was held, and spoke candidly with Robinson after.2

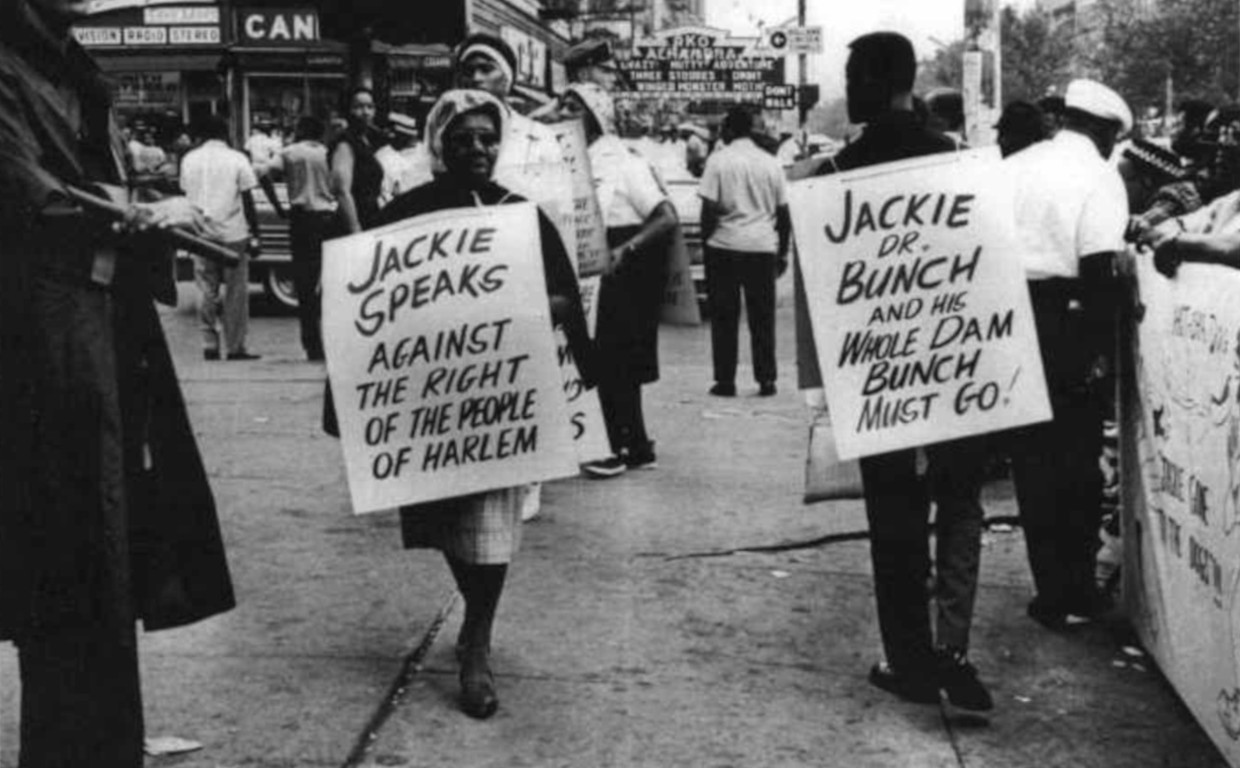

After Robinson denounced the protestors for using antisemitic slogans, Michaux’s group began to target the Chock full o’ Nuts in Harlem. Robinson, who was a vice president at Chock at the time, was specifically targeted. The New York Public Library

The next year, Robinson began to use his weekly column in the New York Amsterdam News to establish a greater distinction between himself and the followers of Malcolm X. In July, after Martin Luther King’s car was targeted by Black nationalist egg-throwers in Harlem, Robinson accused Malcolm of leading the barrage, though Malcolm denied any involvement. “Malcolm has just as much right to be opposed to Dr. King as anyone else,” Robinson noted in the Amsterdam News.3 He even went a step further, suggesting that he himself didn’t agree with King’s philosophies: “I am not and don’t know how I could ever be non-violent. If anyone punches me…you can bet your bottom dollar that I will try to give him back as good as he sent.” Robinson, however, continued by noting that King and his integrationist allies represented the will of America’s Black population, rather than Malcolm X. He reiterated that it was “unfair” for King to be attacked this way, and even went as far as to suggest that Malcolm’s movement was being secretly funded by “important aid and sponsorship from outside the race.”4

Robinson continued his salvo that November, when he wrote in defense of Ralph Bunche, after Malcolm accused Bunche (then a well-known U.N. diplomat) of being a voiceless pawn of the American government.5 This column, though it focused primarily on similar attacks made by Congressman Adam Clayton Powell, resulted in a biting response from Malcolm, itself published in the pages of the News: “You became a great baseball player after your White Boss (Mr. Rickey) lifted you to the major leagues…bringing much money through the gates and into [Rickey’s] pockets,” Malcolm began.6 He then continued by outlining other points of disagreement with Robinson: Malcolm condemned Robinson’s 1949 testimony against Paul Robeson in front of the House Un-American Activities Committee, as well as his close associations with Nelson Rockefeller and Richard Nixon, two Republican politicians who were not particularly well-liked by many Black New Yorkers. Finally, Malcolm cautioned Robinson that many of his white allies may someday turn on him and “be the first to put the bullet or the dagger in your back.”

Jackie Robinson poses with New York Governor Nelson Rockefeller in February 1966. When Rocky won re-election in November that year, he underperformed in Black neighborhoods in Brooklyn and Manhattan. Associated Press

Most of all, Malcolm X viewed many of Robinson’s actions as a betrayal. Writing in his autobiography in 1965, Malcolm recounted how closely he followed the early career of Jackie Robinson while he was in prison.7 A decade and a half later, however, he believed that Robinson had gone astray. Though the attacks were personal, Malcolm’s critique reflected the sentiment among some Black New Yorkers that Robinson had grown out of touch with the radical demands of the 1960s. Many Harlemites may have had the same questions about Robinson’s support for these politicians as Malcolm did, or had been hurt by Robinson’s testimony against Robeson years before. Robinson, already used to receiving hate mail of all sorts, received a deluge of letters criticizing his statements against Malcolm X and Adam Clayton Powell.8

In the broadest of senses, the conflict was a clash of politics and wills. Both sides drew new lines in the debate between integration and nationalism that has animated conversations around race since the arrival of the first slaves in the colonies that would become the United States. But it was also a conflict over strategy and tactics, shaped by the rapidly-crystalizing alliances that were forming in the movement. Robinson, for example, often merely accused Malcolm of being a figment of the white media, rather than a leader with a substantial following.9 Such a rhetorical flourish was almost certainly influenced by the politicking of some of his close allies: In 1961, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, on whose board of directors Robinson served, denounced the Nation of Islam as a hate group at its annual convention.10 Later, in 1966, NAACP executive director Roy Wilkins would go on to denounce Black Power more broadly, describing it as the “reverse” of Klan tactics in use in Mississippi.11

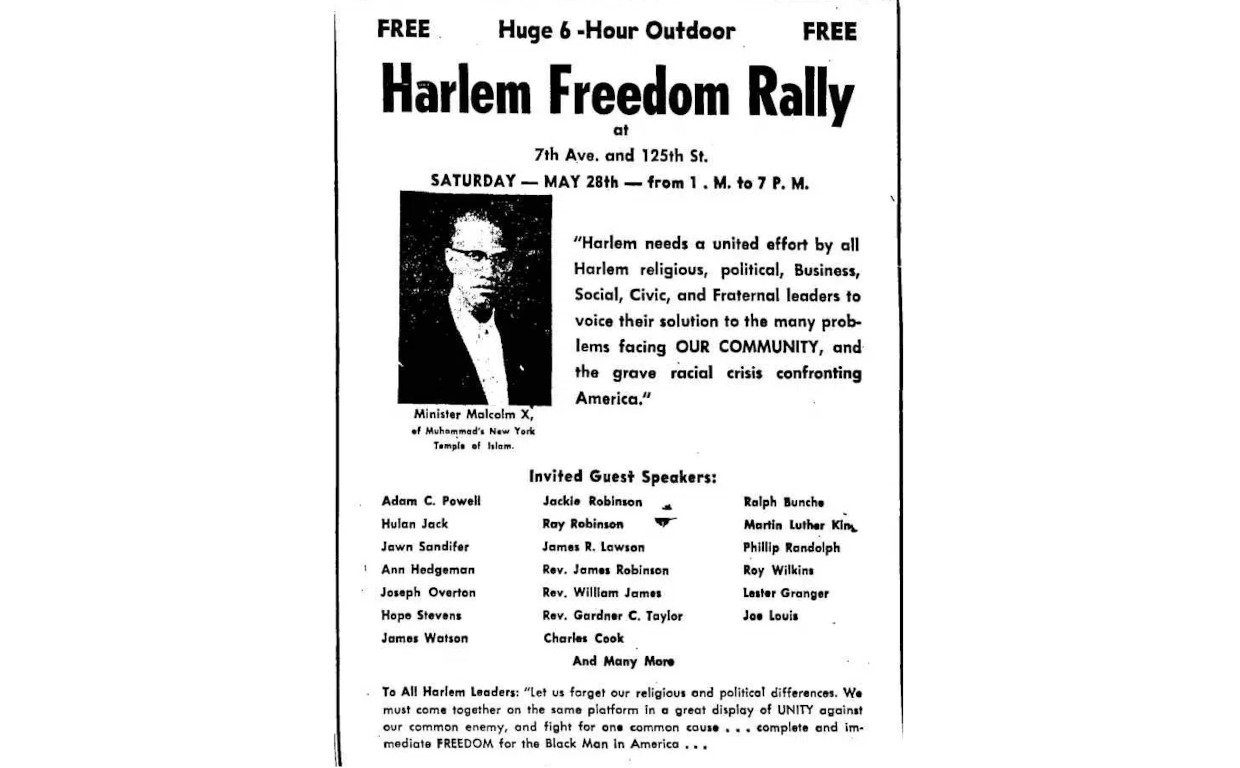

On May 28 1960, Malcolm X hosted a “freedom rally” in Harlem, to which a number of Black celebrities were invited. Robinson did not attend. New York Amsterdam News

Moreover, the conflict was borne out of the reality that neither fully understood how the other earned the support of everyday Black people across the country. Robinson did not yet at this time appreciate the importance of the work the Nation of Islam was able to accomplish around police brutality and accountability within major cities. Moreover, Robinson’s labeling of Malcolm as a firebrand devoid of ideology ignored the Nation’s attempts to ally with more “mainstream” organizations in the early part of the decade.12 Likewise, Malcolm X was generally unwilling to believe in Robinson’s ability to activate marchers and protestors in the cities and towns he visited across the South. By accusing Robinson of being a pawn of “white bosses,” he showed disinterest in the work Jackie had done to support the on-the-ground struggle, especially when it was stagnating locally or in need of money for bail. Both parties accused each other of leading the growing movement in the wrong direction, and said so sharply and openly.

It must be remembered, of course, that the conflict between Robinson and Malcolm X should not be interpreted as an intractable split between parts of the freedom struggle. As contemporary historians such as Timothy Tyson and Charles Cobb have noted, the line between “nonviolence” and “militancy” was often blurred, especially in the Southern states where the movement was being forged.13 Further, Robinson and Malcolm X had more than a few areas of agreement, including the need to fight for Black economic independence.

Robinson also shared Malcolm’s skepticism of Martin Luther King’s emphasis on nonviolence, though he was willing to put aside such tactical differences as he collaborated with King. An astute reader of the New York Amsterdam News would have had access to this debate in real time, and could use the words of the two thinkers to understand their own positionality within a rapidly-shifting political environment.

Jackie Robinson and Lewis Michaux shake hands following their 1962 debate. New York Public Library

Malcolm X was assassinated on February 21, 1965 in the Audubon ballroom in Harlem. By then, he had distanced himself from the Nation of Islam and was increasingly being harassed by its members (as well as federal agents) prior to his murder. Upon his death, Robinson remarked that he rarely agreed with Malcolm’s prescriptions for the movement, though he affirmed that “many of the statements he made about the problems faced by the Negro people were nothing but the naked truth.”14 Mostly, Robinson admired Malcolm as someone who said what he believed, and did so plainly and forcefully, not unlike Robinson himself. The brief eulogy offered by Robinson in print was not one of reluctant acquiescence or false sentimentality. It was simply written out of respect for a man whose powerful voice would help define the struggle for racial equality for decades to come.

Robinson and Malcolm X had radically different visions for Black America in the 1960s. They operated within different channels of the movement and viewed each other with distrust, if not open contempt. Even so, the disagreement was productive: Their conflict, openly bared and syndicated on the pages of Black newspapers, allowed readers themselves to participate in the debates around integration and nationalism that were taking shape. The pair never got a chance to settle their differences. Both died at a fairly young age in the midst of an unfinished struggle for racial justice. Even so, the words they left behind continue to inform conversations about the Black American experience and the reality of disagreement within a mass movement.

To explore the relationship between Jackie Robinson, Malcolm X, and other prominent Harlem civil rights leaders, check out Jackie Robinson’s Harlem available for free online or as a walking tour.

References

- Jackie Robinson, “Strange Happenings On West 125th St.,” New York Amsterdam News, July 14, 1962.

- Lewis H. Michaux, “Cooperation And Unity: A Way Out: Peace, It’s Wonderful,” New York Amsterdam News, July 28, 1962.

- Jackie Robinson, “Egg-Throwing And Dr. King,” New York Amsterdam News, July 13, 1963.

- Ibid.

- Jackie Robinson, “Malcolm X And Adam Powell,” New York Amsterdam News, November 16, 1963.

- Malcolm X, “Malcolm X’s Letter,” New York Amsterdam News, November 30, 1963.

- Malcolm X and Alex Haley, The Autobiography of Malcolm X (New York: Grove Press, 1965), 126.

- Arnold Rampersad, Jackie Robinson: A Biography (New York: Knopf, 1997), 381.

- Jackie Robinson, “Umpire Jackie Robinson Calls Errors He Sees–By Black and White,” New York Herald Tribune, April 26, 1964, Jackie Robinson Museum, see also: Jackie Robinson, “Mysterious Malcolm,” New York Amsterdam News, May 2, 1964.

- Garrett Felber, Those Who Know Don’t Say: The Nation of Islam, the Black Freedom Movement, and the Carceral State (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2020), 93.

- Simon Hall, “The NAACP, Black Power, and the African American Freedom Struggle, 1966–1969,” The Historian 69, no. 1 (March 1, 2007): 58.

- Felber, Those Who Know Don’t Say, Chapter 3

- See, for example Charles E. Cobb, This Nonviolent Stuff’ll Get You Killed: How Guns Made the Civil Rights Movement Possible (Durham: Duke University Press Books, 2015), and Timothy B. Tyson, Radio Free Dixie: Robert F. Williams and the Roots of Black Power, First Edition (Chapel Hill London: The University of North Carolina Press, 2001).

- Jackie Robinson, “Some Warmth Is Gone,” The Chicago Defender, March 6, 1965.

On April 15, Jackie Robinson crossed the foul lines of Brooklyn Dodgers’ Ebbets Field and took up his position at first base. As he did so, he became the first Black major league player since 1884, ending the secretive, league-wide “gentlemen’s agreement” among team owners to refrain from hiring Black ballplayers. It was Robinson’s first step in a ten-year major-league journey that would include a Most Valuable Player award, six National League pennants, and a World Series ring. But when Robinson stepped into the batter’s box and faced the dizzying curveballs of the Boston Braves’ Johnny Sain, he was just number 42, trying to make good on baseball’s biggest stage.

Robinson’s debut received a wide range of reactions in the press: The local white dailies in New York seemed largely indifferent, with some papers not even bothering to mention Robinson at all. In Black newspapers across the country, however, Robinson’s promotion to the Dodgers and first games in Brooklyn were front-page news as photographers and reporters celebrated his arrival and prognosticated about his future with the team. Robinson knew he was making history that day. He also understood that there would be a long road ahead.

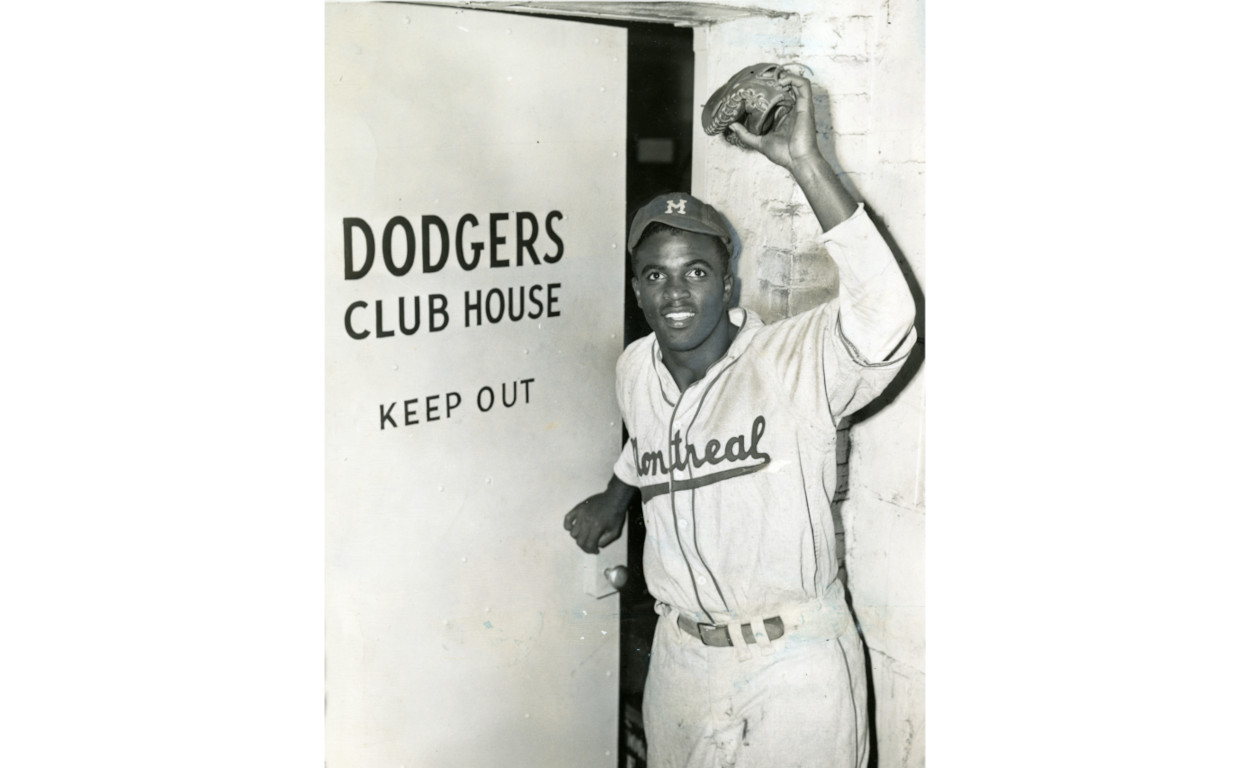

Jackie Robinson enters the Dodgers clubhouse on April 11, 1947 after the team purchased his contract from the Montreal Royals. National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

By the final weeks of Spring Training in 1947, Jackie Robinson’s promotion from the Montreal Royals minor league squad to the Dodgers was not certain. Though he had a remarkable season in 1946, he had a difficult spring in Panama and Cuba, battling Jim Crow accommodations and stomach illnesses as he tried to make the team. As the teams headed north, Robinson still remained formally a member of the Montreal Royals.

Prior to Opening Day against Boston, the Dodgers played four exhibition games, one against their Royals farm club and three more against the Yankees. On April 10, the day of the first game, Robinson’s contract was formally purchased by the Dodgers, elevating him to the major league squad. The series drew almost 100,000 fans across the games, close to double the previous season’s exhibition total. “Robinson is the attraction,” declared Wendell Smith, sports editor of the Pittsburgh Courier and a close confidant of Jackie. “There is no doubt that Negro fans are showing their appreciation by digging down and coming up with money for tickets every day.”1 Even before the official start of the season, it was clear that Robinson would be a major draw.

Soon, it was time for Opening Day. As Jackie prepared for the game, his wife Rachel and infant son Jackie Jr. began their journey from their temporary home at the McAlpin Hotel in Herald Square to Ebbets Field in Brooklyn. Not wanting to get lost on the subway, Rachel tried in vain to hail a cab. Most turned her down. Whether it was because of the distance, Rachel and Jackie Jr.’s race, or some combination of both, she wasn’t sure. But eventually, she was able to get to the stadium in time to see Jackie play.

Rachel and Jackie Jr. join Ruth Campanella (left) at Ebbets Field on April 15, 1947. Rachel enlisted the help of a hot dog vendor to warm Jackie Jr.’s bottle of milk. Jackie Robinson Museum

The Dodgers opened the 1947 season against the Boston Braves in front of a crowd of about 25,000 fans. Robinson batted second, between second baseman Eddie Stanky and center fielder Pete Reiser. Just as he did in the exhibition games, Robinson played first base that day, taking his position in the infield alongside Stanky, Dodger stalwart Pee Wee Reese at short, and fellow rookie Johnny “Spider” Jorgensen at third. First base was a new position for Robinson: He played primarily middle infield positions in college and with the Negro Leagues’ Kansas City Monarchs, and spent most of the previous season in Montreal at second base. Even so, he performed exceptionally, going a perfect 11-for-11 in the field.

At the plate, though, Robinson was less successful. He was up against Boston’s Johnny Sain, a fiery curveballer who would go on to win 21 games that year. In his first trip, Robinson grounded to third for the second out of the first inning. In the bottom of the third inning, Robinson flew out to left, ending a 1-2-3 frame. In the fifth inning, with runners on the corners and one out, Robinson lashed a dribbler through the box that looked like it would be his first career hit and run batted in.2 Instead, Boston shortstop Dick Culler snagged the grounder, flipped it to the second baseman, who spun and threw to first, beating Robinson by a hair for an inning-ending double play.

Robinson faced Sain once more in the bottom of the seventh, with none out and the Dodgers down 2 to 3. After Eddie Stanky drew a walk, Robinson laid down a stellar sacrifice bunt, a scrappy move that would come to define Robinson’s style of play for a decade. A wild throw to first allowed Robinson to advance a base, and by the time the ball was returned to the infield, Stanky had checked in at third as well. Pete Reiser came to the plate next and immediately lashed a double to right, scoring both Robinson and Stanky and giving Dem Bums a 4–3 lead. Two batters later, Gene Hermanski scored Reiser with a sac fly, extending a lead that would be preserved for the rest of the game.