News

The Jackie Robinson Museum Is About a Lot More Than Baseball

Robinson accomplished a great deal on the field, but a museum celebrating his life puts as much focus on his civil rights work.

READ MOREPlan your visit or become a member today! Speak Out! Student Poster exhibit now on view.

Every March, American and National League Teams descend on cities and towns in Florida to prepare for the baseball season and to determine which players will make their big-league squads and get in shape for the long season ahead. For Black players, spring training in the decades after integration put them squarely in the sights of Florida’s Jim Crow laws, where they were forced to navigate substandard accommodations, limited public transportation and other daily indignities.

Jackie Robinson with teammates at Dodgertown, Vero Beach, Florida, circa 1950. Getty Images.

By 1948, Jackie Robinson had largely been accepted in Flatbush as the first Black major leaguer, and many more Black players were working their way through the expansive system of Dodger farm clubs. But to have all the Dodgers train in Florida, decisions would need to be made to accommodate the growing roster of African American players.

The solution came in the form of abandoned Navy barracks in the town of Vero Beach. Branch Rickey and the Dodgers purchased it in 1948 and quickly christened it “Dodgertown.” As Black players joined the Dodgers and their minor-league affiliates, they would have a place to stay with the team as equals.

Images of Dodgertown, 1948-1955. Walter O'Malley Collection, Indian River Historical Society, Getty Images.

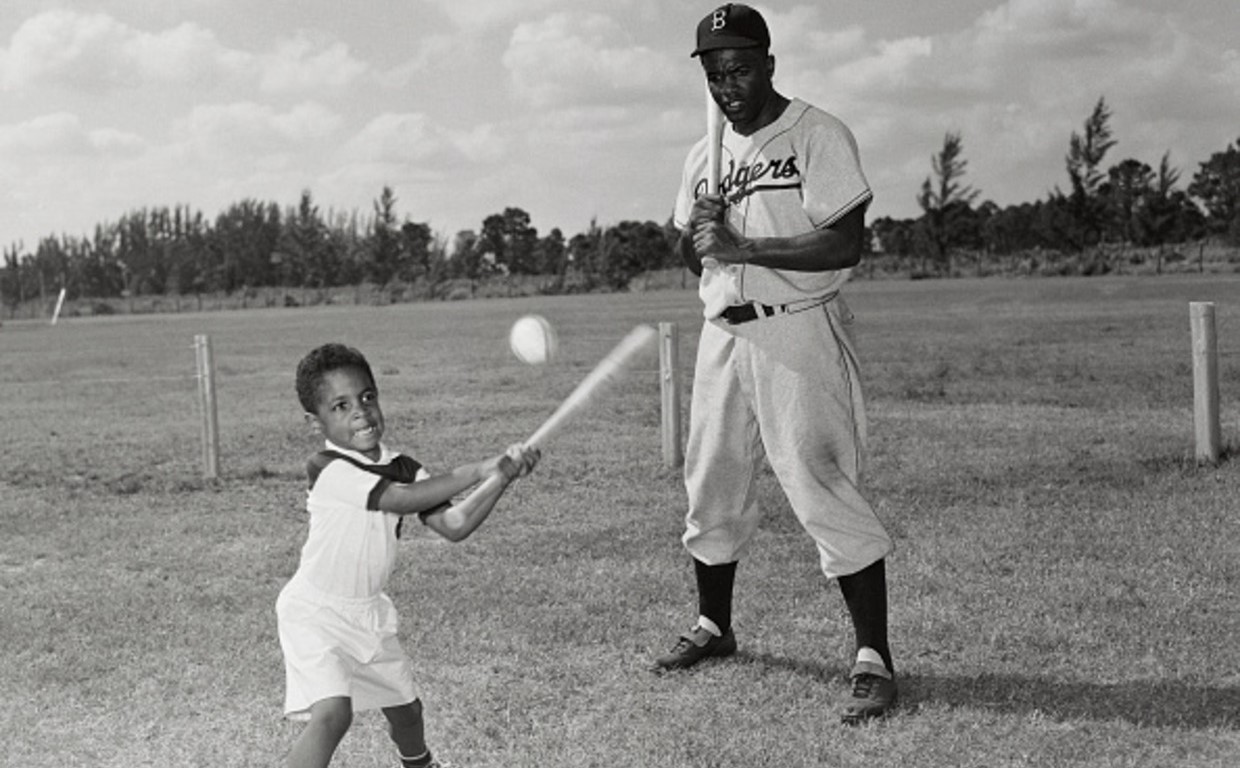

Compared to the difficulty of 1946, when Jackie Robinson and fellow Black player Johnny Wright stayed with a local family in Daytona, this was an improvement. Gone were the days of shuttling back and forth from distant neighborhoods to the ballpark. At Dodgertown, players and their families were able to eat in a well-appointed, integrated canteen on-site. Later, Dodgers ownership added a movie theater and a pitch-and-putt golf course as well, offering further opportunities for recreation for players. Jackie’s wife Rachel and toddler son Jackie Jr. were able to visit and spend time in the sun, away from both the cold northeastern winter and segregated Florida restaurants and hotels. Jackie Jr. would play on the fields, wave to fans in the stands, and drink fresh-squeezed orange juice.

Despite the care taken by the Dodgers to minimize the harm to their players from Florida’s Jim Crow laws, they were not protected when they left the base. In his autobiography, Jackie described how Rachel was unable to get her hair done in predominantly white Vero Beach. Not wanting to get lost on public transportation, she called a cab to take her and Jackie to a beauty shop in a Black neighborhood. The driver refused to serve her, telling her she needed to call a “colored cab.” Soon, she realized there was no such thing, and was forced to take a dilapidated bus across town.

Jackie Robinson and his son Jackie Jr. practice hitting at spring training at Dodgertown, 1949. Bettmann Archive, Getty Images.

Such humiliations were a part of the annual ritual of spring training in Vero Beach. After all, despite the improvements, Black players like Jackie Robinson, Don Newcombe, Roy Campanella, and Jim Gilliam were limited to the amenities at Dodgertown or “Black only” venues offsite . Dodgers ownership even provided Gilliam with a car so that he could take other Black players to the nearby town of Gifford for off-base recreation.

(L to R) Unidentified, Roy Campanella, Herb Scharman, Barney Stein, Unidentified, and Joe Black after a day of fishing near Dodgertown, ca. 1952. Walter O’Malley Collection

The Dodgers remained in Vero Beach until 2008, when the team’s spring training headquarters moved to Arizona. For many team personnel, the move represented the end of a nostalgic era. Others, like Don Newcombe put it more bluntly. “I have no good memories of Vero,” he later said. For many Black players, Dodgertown represented both hope for the future of integration of baseball and despair at the realities of their segregated present.

After the 2008 move, the facility owned by the Indian River community was initially managed by minor league baseball, but in 2014 management was returned to former Dodgers’ owners Peter and Teri O’Malley and their partners Hideo Nomo and Chan Ho Park, both former Dodgers’ pitchers. In 2019, Major League Baseball took over operations and renamed the site the Jackie Robinson Training Complex, which plays host to a number of tournaments each year for young players looking for high levels of competition. The ball fields and batting cages have been put to new use –giving younger generations a chance to hone their skills on hallowed ground.

Resources:

Jackie Robinson and Alfred Duckett, I Never Had It Made (New York, Putnam, 1972)

Ross Newhan, “It Wasn’t the Happiest Camp for Everybody,” Los Angeles Times, February 10, 2008

Ross Newhan, “Dodgers Headed Way Off-Base,” Los Angeles Times, February 10, 2008

Ray McNulty, “Dodgertown Looks Great Worthy of Its Glorius Past,” Vero News, June 17, 2021

News

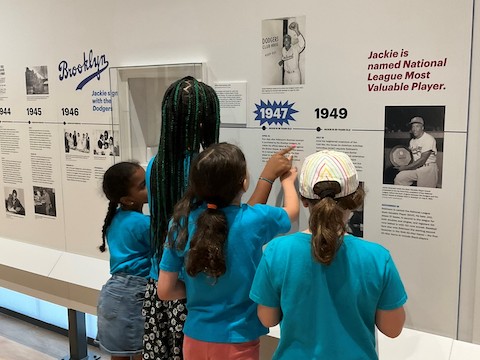

Robinson accomplished a great deal on the field, but a museum celebrating his life puts as much focus on his civil rights work.

READ MORE

News

Visitors will also get to explore an immersive experience “to better understand the racism and prejudice Robinson encountered beyond the baseball field, as well as stories of his lasting influence on sports, politics and entertainment today.”

READ MORE

Programs & Events

Get the scoop on new programs and resources for teachers, students, and families!

READ MORE