News

The Jackie Robinson Museum Is About a Lot More Than Baseball

Robinson accomplished a great deal on the field, but a museum celebrating his life puts as much focus on his civil rights work.

READ MOREPlan your visit or become a member today! Speak Out! Student Poster exhibit now on view.

Although Barry Goldwater’s wide margin of victory didn’t show it, the 1964 Republican National Convention was one of the most contentious and influential moments in modern American politics. It heralded the rise of the modern conservative movement, almost fully marginalized the liberal wing of the Republican Party and severed the last vestiges of Black support for the GOP. Jackie Robinson, a liberal and a special delegate of New York Governor Nelson Rockefeller, got a firsthand look at the changing face of the party from the convention floor. What he saw and experienced would change his political outlook for the remainder of his life.

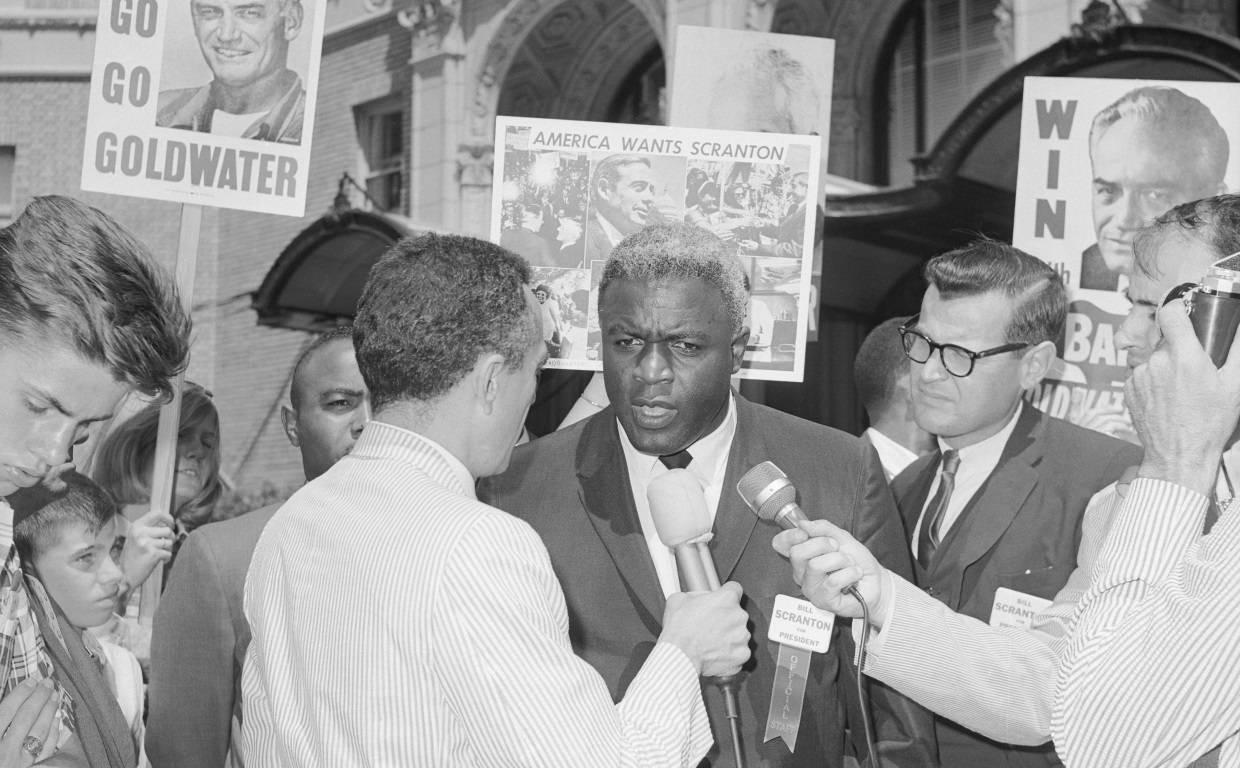

Jackie Robinson speaks to reporters before the convention on July 10, 1964. Getty Images

By the time the party gathered in the sweltering heat of the Cow Palace, an arena near San Francisco, Jackie Robinson had been sounding alarm bells about Barry Goldwater, the presumptive nominee, for months. As far back as August 1963, Robinson warned of Goldwater’s ascendence within the party.1 The Arizona senator was by all accounts a segregationist. He voted against the 1964 Civil Rights Act and quickly became the choice of voters who wished to roll back gains on school integration and voting rights.2 Certainly, this was by design. Goldwater and his supporters were fond of declaring that the Republican Party should “go hunting where the ducks are,” courting the votes of those who had opposed the civil rights advancements made under the Kennedy administration.3 For delegates like Robinson, the nomination of Goldwater was unconscionable. It had to be averted at all costs, lest the GOP become, as Robinson bluntly put it in a 1963 Saturday Evening Post article, “for white men only.”4

In 1964, Nelson Rockefeller hired Robinson as a special assistant for community affairs. Here, Robinson joins him at an election night party in 1966, at which Rockefeller was elected to a third term as Governor of New York. Getty Images

Robinson’s ardent opposition to Goldwater had pushed him towards Nelson Rockefeller’s camp over the course of the campaign cycle. Rockefeller, midway through his second term as New York governor, represented the liberal wing of the Republican Party, and had earned Robinson’s favor early in the race. Throughout most of his life, Robinson had identified as a Republican. This in itself was not unusual. For most of the previous three decades, both major U.S. parties had been held together by unusual coalitions, often with wide ideological gulfs between them. The Democrats comprised an alliance between New Deal populists and Southern segregationists, while the Republicans were supported by a diverse range of northern liberals and pro-business conservatives. As a result, Black voters were often torn between two poles, neither of which could be fully trusted to push for racial and economic equality.

In 1960, this ground was shifting. Democratic nominee John F. Kennedy commanded a decisive majority of Black voters, even as Robinson himself supported Republican Richard Nixon, whom he deemed more trustworthy on the issue of civil rights. While many organizers often bemoaned the slow pace of change even after Kennedy was elected, he proved to be more receptive to the demands of the movement than his predecessor had been. By the time he was assassinated at the end of 1963, Kennedy had earned the support and sympathy of much of the Black electorate. A poll conducted shortly after the assassination revealed that eighty percent of Black voters surveyed compared the president’s death to the passing of a close relative. Others feared the assassination would derail civil rights progress.5

Robinson shakes hands with Richard Nixon at a campaign event in 1960. Even by 1963, Robinson had grown wary of Nixon’s changing stances on civil rights.6 “I began to suspect,” Robinson later lamented, “that personal ambition was the dominant drive behind this man.”7 Associated Press

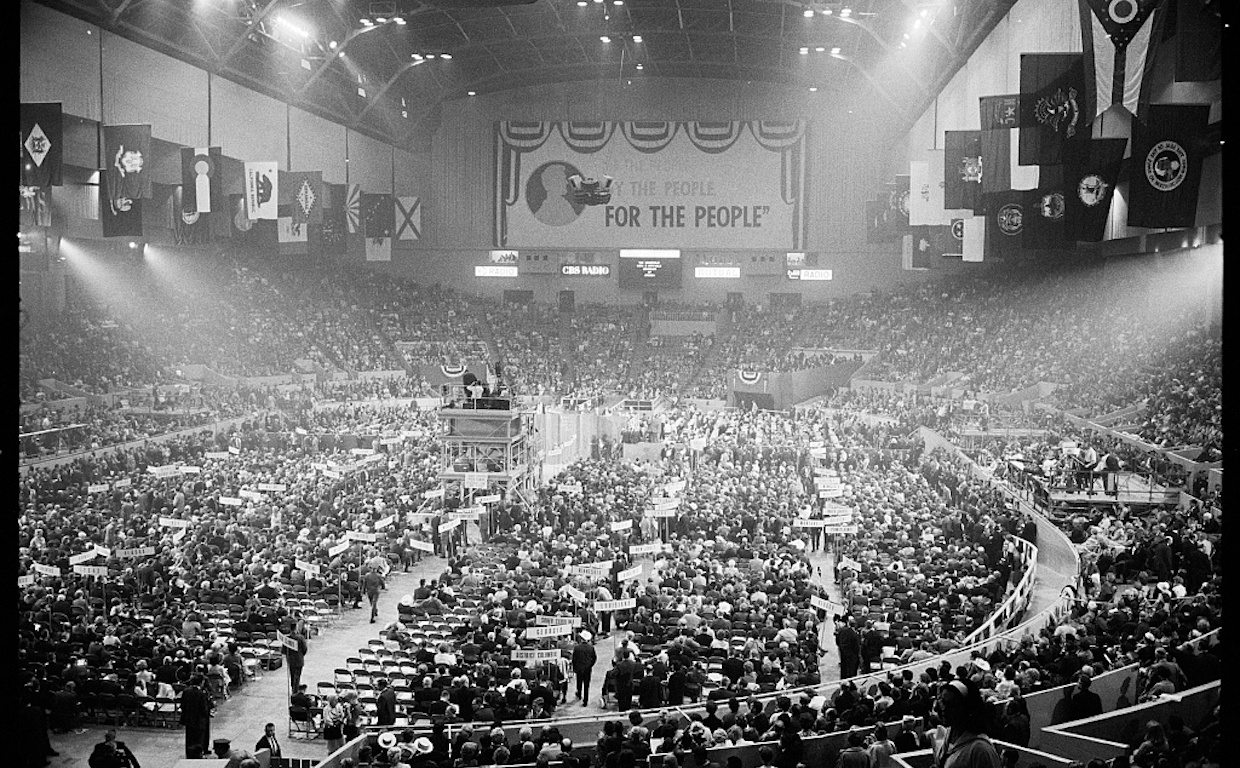

As Robinson entered the Cow Palace in 1964, he remained hopeful that the Republican Party would avoid nominating Goldwater and preserve at least some of its commitments to the still-growing movement. On the floor of the convention, however, his fears quickly materialized. On the second day, Robinson and the other Rockefeller supporters attempted to add a plank to the party platform condemning the extremism of the Ku Klux Klan and the John Birch Society.8 The motion failed, to the raucous applause of a majority of the delegates. As Rockefeller’s bid for the nomination likewise went down in flames, Robinson and his other supporters rallied around the candidacy of Pennsylvania Governor William Scranton. This attempt quickly collapsed as well. Goldwater won the nomination handily on the first ballot.

Delegates fill the Cow Palace on July 13, 1964. Wikimedia Commons

Late in the evening, Nelson Rockefeller was finally given a chance to speak. He again denounced the extremism of Goldwater and was drowned out by boos from an agitated crowd.9 Robinson, almost entirely alone in his support, shouted his praise of Rockefeller from the floor. When he did, a nearby delegate rose to confront him. Had it not been for the delegate’s wife holding him back, Robinson later said, they might have come to blows. The other Black delegates, who amounted to just fifteen out of well over a thousand, were similarly mistreated.10

During the convention, churches and labor groups sponsored a civil rights march through San Francisco. Marchers, many carrying anti-Goldwater signs, protested the reactionary politics of the nominee. Library of Congress

Goldwater would go on to lose to Democrat Lyndon Johnson in a landslide that November. For Robinson, the disaster of the convention essentially marked the end of his association with the Republican Party at the national level. Robinson thought he and Black voters had a seat at the table, but they were quickly silenced by a tide of reaction that swept through the convention in 1964. Robinson believed that the Goldwater nomination would signal the permanent demise of the Republicans. Four years later, he would be proven wrong: Richard Nixon, hardened in his opposition to the growing militancy of the Civil Rights Movement, won the presidency four years later with a strategy similar to Goldwater’s.

It was a crushing defeat for Robinson’s political worldview. In the early 1960s, Robinson believed that civil rights victories could be won at the administrative level by ensuring that both major parties would need to compete with each other for Black voters.11 But by the middle of the decade, it became clear that the Republican Party had no interest in winning back the groups whose support had shifted.12 Though Robinson’s belief in the functionality of the two-party system was shaken, he continued to be civically engaged for the rest of his life, fighting to support the candidates he believed would join him in demanding racial and economic justice in the United States.

Click to view this July 10, 1964 interview with CBS 8 reporter Harold Keen.

Robinson strove to be a part of the political process through whatever means were available to him. Whether he was operating inside the system as a convention delegate or campaign surrogate, or outside of it as a protestor or columnist, Robinson understood that the fight didn’t end after the first Tuesday in November. Even so, he never failed to stress the importance of voting rights and political participation to his allies and supporters across the country. As he left San Francisco in 1964, Robinson understood that his defeat at the convention was the beginning of a new era. Robinson’s beliefs had not changed—rather, the shifting alliances of electoral politics were pushing him in new and unexpected directions. As the tumult of the sixties produced both victories and defeats, Jackie continued to rise to the challenge to demand first-class citizenship for all.

The Jackie Robinson Museum remains committed to voting rights across the United States. If you aren’t registered to vote, please visit vote.gov to register prior to Election Day on November 5, 2024 (deadlines vary by state). Visitors to the Museum can access this site from a kiosk located near the lobby, immediately behind the elevator.

[1] Jackie Robinson, “Jackie Robinson Says: Has Goldwater Taken Over For the GOP?,” Michigan Chronicle, August 10, 1963, sec. Editorial Page.

[2] Leah M. Wright, “Conscience of a Black Conservative: The 1964 Election and the Rise of the National Negro Republican Assembly,” Federal History 1 (2009): 32.

[3] Stewart Alsop, “Can Goldwater Win in 64?,” Saturday Evening Post, August 8, 1963.

[4] Jackie Robinson, “The G.O.P.: For White Men Only?” Saturday Evening Post, August 10-August 17, 1963

[5] Sharron Wilkins Conrad, “More Upset Than Most: Measuring and Understanding African American Responses to the Kennedy Assassination,” American Quarterly 75, no. 2 (2023): 279–307.

[6] Jackie Robinson, “An Open Letter To Dick Nixon,” New York Amsterdam News, May 4, 1963.

[7] Jackie Robinson, “Did Goldwater Promise Nixon?,” New York Amsterdam News, November 21, 1964.

[8] “In The High Drama Of Its 1964 Convention, GOP Hung A Right Turn,” All Things Considered (NPR, July 10, 2014), https://www.npr.org/2014/07/10/330496199/in-the-high-drama-of-its-1964-convention-gop-hung-a-right-turn.

[9] Jackie Robinson and Alfred Duckett, I Never Had It Made (New York, Putnam, 1972),

http://archive.org/details/ineverhaditmade00robi.

[10] Wright 2009, 35

[11] Jackie Robinson, “Negroes Know Their Enemies,” New York Amsterdam News, February 24, 1962, see also “Baseball Great Jackie Robinson Talks about Politics in San Diego in the 1960s” (CBS, July 10, 1964), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WaRk0-OEUKg.

[12] Alsop, “Can Goldwater Win in 64?”

News

Robinson accomplished a great deal on the field, but a museum celebrating his life puts as much focus on his civil rights work.

READ MORE

News

Visitors will also get to explore an immersive experience “to better understand the racism and prejudice Robinson encountered beyond the baseball field, as well as stories of his lasting influence on sports, politics and entertainment today.”

READ MORE

Programs & Events

Get the scoop on new programs and resources for teachers, students, and families!

READ MORE