News

The Jackie Robinson Museum Is About a Lot More Than Baseball

Robinson accomplished a great deal on the field, but a museum celebrating his life puts as much focus on his civil rights work.

READ MOREClosing Early on July 3rd and Closed on July 4th. Plan your visit or become a member today! Speak Out! Student Poster exhibit now on view.

Though Jackie and Rachel Robinson were California natives, they became New Yorkers through their work, service, and deep investment in the city’s local communities.

When Jackie and Rachel Robinson moved from the McAlpin Hotel in Manhattan to an apartment in Brooklyn in the middle of 1947, they quickly sought to make the Flatbush neighborhood their new home. Jackie’s life as a public figure and role model for youth around the country was a busy one, even in the offseason. During his baseball career, Jackie found ways to become a part of New York’s civic and economic life—and draw a paycheck—when he wasn’t circling the bases at Ebbets Field.

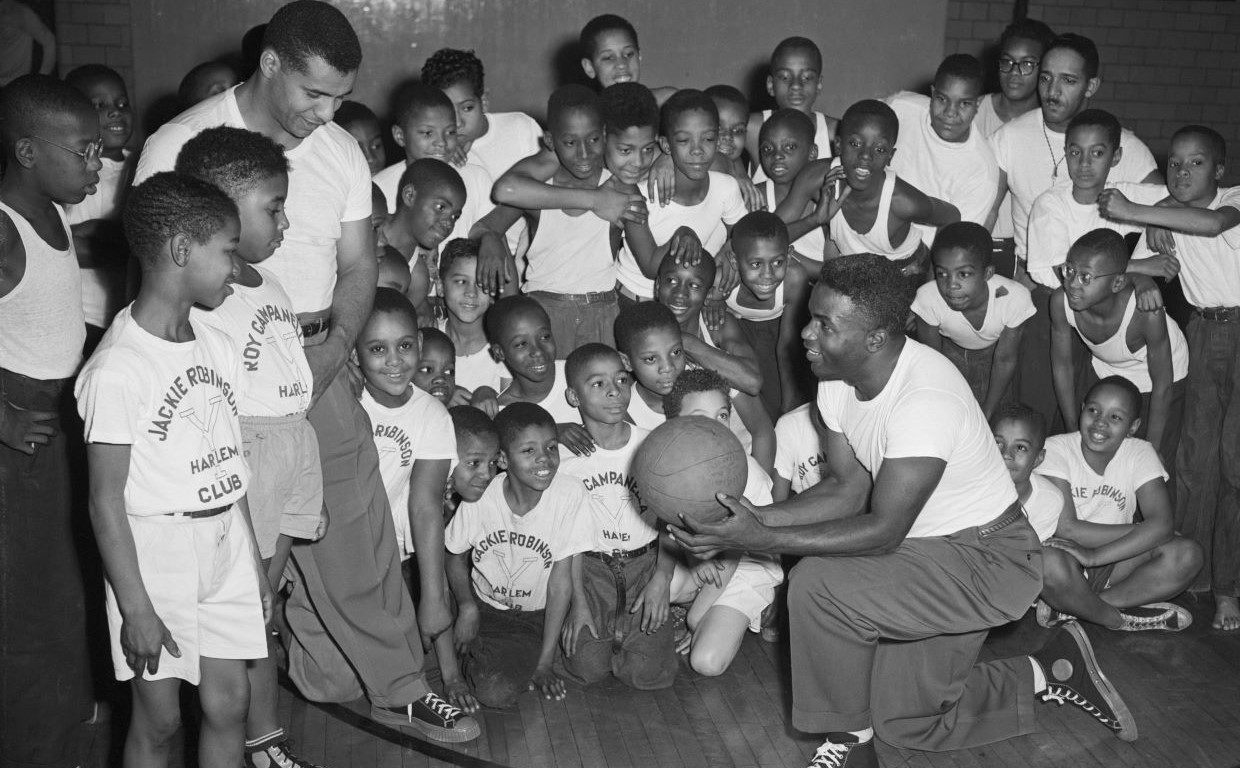

Jackie and Roy Campanella coach basketball at the Harlem YMCA, 1948. Courtesy of Getty Images

Robinson’s first and longest-lasting foray into community work began in the offseason in 1948, when he and Roy Campanella signed up to be youth coaches at the Harlem branch of the YMCA. For Robinson, this was a familiar way to show support for the Black communities in the city. After leaving UCLA, Robinson was a youth coach with the National Youth Administration in California, and he coached basketball in Texas as well. Although the pay was minimal, it allowed Robinson to live out his closely held belief that children’s access to sports and recreation were key to their social and mental development.

Sugar Ray Robinson purchases a TV from Jackie Robinson at Sunset Appliance, Rego Park, Queens, NY, 1949.

In the middle of the 1949 season, Jackie, Rachel, and Jackie Jr. moved further east, to St. Albans, Queens. Other Black celebrities had moved to the area as well in the 1940s, and Jackie and the family were excited to build connections in a new neighborhood. At the end of the season, Jackie took on a new job in nearby Rego Park as a TV salesman. Though Robinson’s short-lived stint at the Sunset Appliance Store might have been a publicity stunt to draw sports fans into the store, he handled the job with aplomb, signing baseballs for kids and chatting with adults as he made sales.

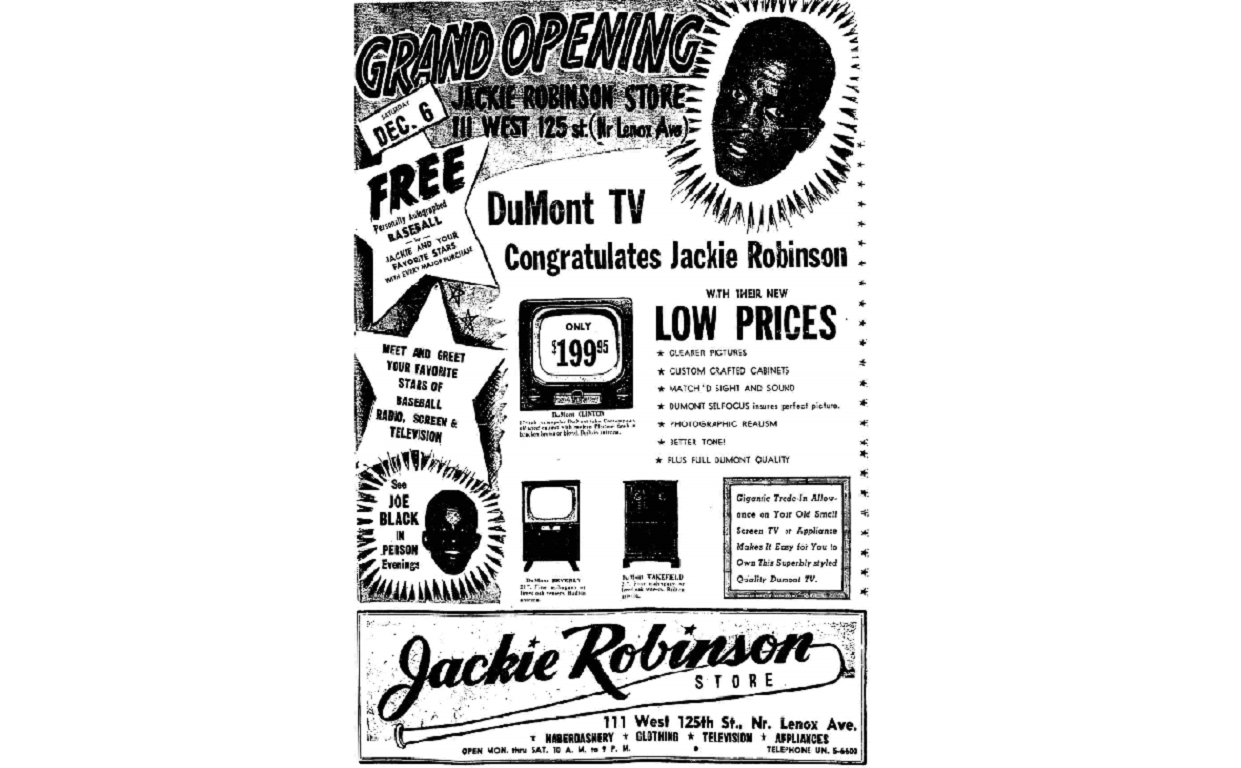

Robinson’s most ambitious business venture to date was the Jackie Robinson Store, which opened on 125th Street in Harlem in 1952. Robinson, who owned a 25% stake in the operation, wanted to open a department store offering high-quality goods to a Black consumer base that was often mistreated in Midtown department stores. Despite his sales experience, Robinson had limited knowledge about running a retail establishment and the store struggled to turn a profit.

An advertisement for the grand opening of the Jackie Robinson Store published December 6, 1952, in the New York Amsterdam News, Harlem’s Black newspaper.

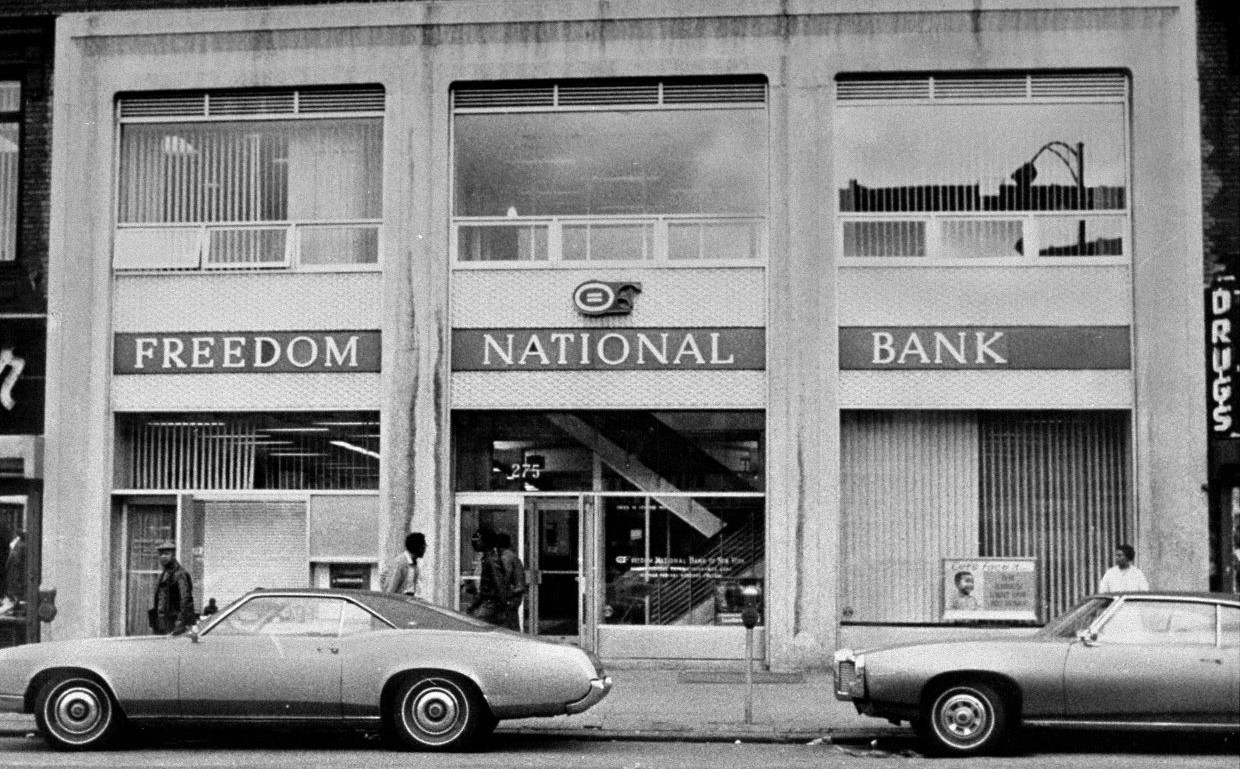

There were other difficulties as well. Because the store was mostly owned by Jackie’s white business partners, many Harlemites doubted that the store was keeping money in the neighborhood. Throughout Robinson’s tenure as a partner, he was forced to answer questions about whether he was merely a “front” for other white owners. Decades of job discrimination and economic disempowerment had left the neighborhood’s Black working-class residents with little to spend, further weakening the store’s bottom line. To improve the fortunes of Harlem, Robinson discovered, would require dignified places to make money as well as spend it. Despite these challenges, Robinson remained committed to bringing business opportunities to Harlem. Later, in 1964, Robinson co-founded Freedom National Bank, a lending institution that could help Black borrowers who might otherwise be frozen out of the financial system obtain mortgages and loans. While it succeeded in expanding many New Yorkers’ access to credit, it was often dogged by many of the same issues and criticisms the store faced a decade earlier.

Exterior view of Freedom National Bank on 125th Street in Harlem, ca. 1975. Courtesy of Getty Images

Jackie continued to invest in the city for the remainder of his life. In addition to writing syndicated newspaper columns in the New York Post and the New York Amsterdam News, Robinson served as a vice president of the Chock Full o’Nuts coffee chain and stepped up among the city’s civil rights activists, debating Malcolm X and using his column to weigh in on issues like school segregation, youth employment, and housing. Over his life, Robinson built connections with businesses and community organizations that left his mark on the urban fabric. Though not all of his ventures were successful, Robinson was committed to using his celebrity and insights to contribute what he could to New York City.

News

Robinson accomplished a great deal on the field, but a museum celebrating his life puts as much focus on his civil rights work.

READ MORE

News

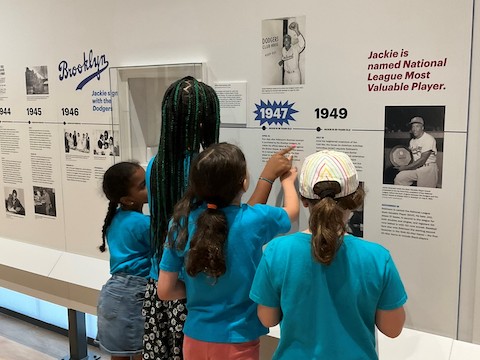

Visitors will also get to explore an immersive experience “to better understand the racism and prejudice Robinson encountered beyond the baseball field, as well as stories of his lasting influence on sports, politics and entertainment today.”

READ MORE

Programs & Events

Get the scoop on new programs and resources for teachers, students, and families!

READ MORE