News

The Jackie Robinson Museum Is About a Lot More Than Baseball

Robinson accomplished a great deal on the field, but a museum celebrating his life puts as much focus on his civil rights work.

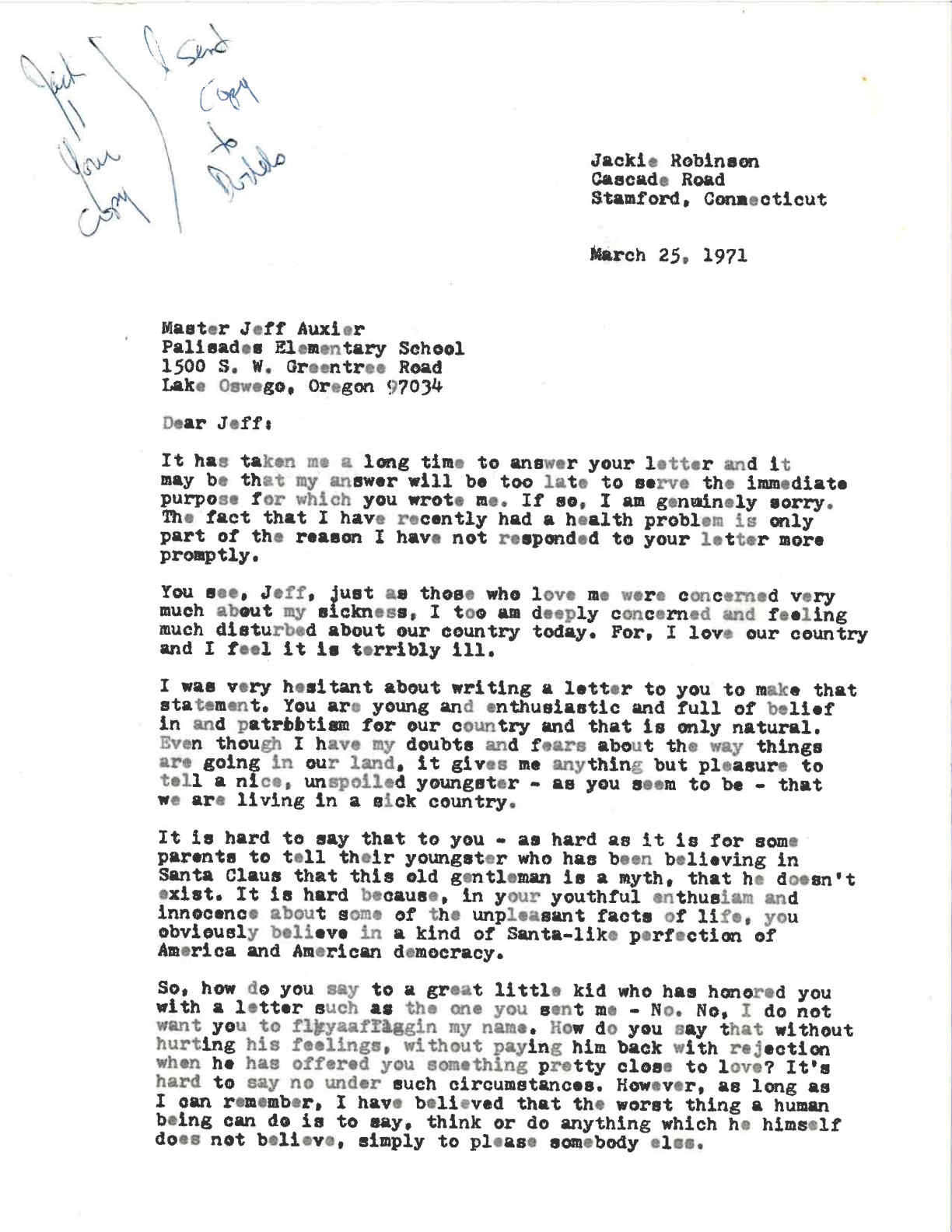

READ MOREIn early 1971, Jeff Auxier, a student at Palisades Elementary School, south of Portland, Oregon, sent Jackie Robinson a letter asking if Robinson would fly an enclosed American flag which was as part of a school project. Robinson responded with a lengthy and thorough letter, revealing the conscience of a ballplayer and civil rights stalwart who was disillusioned with the state of the country and was ready to pass the baton on to the next generation to continue the fight for civil rights and racial justice.

By March 25, when Jackie sent his response, his health was failing him. He had been hospitalized earlier that year and his vision was fading. In the opening to his reply, he apologized for his difficulties in getting back to Auxier, both in terms of how long it took to respond, and for the painful words that he needed to write. How would Robinson respond to a young child, full of patriotic hope for the United States, when Robinson himself knew that he had almost none left?

Copy of the first page of a letter by Jackie Robinson sent in response to a request to fly an American flag from elementary school student, Jeff Auxier, March 21, 1971. Jackie Robinson Museum Collection

Jackie knew what he had to say: No, Jackie Robinson would not fly an American flag at all. The country, he lamented, was “sick.” As the American war in Vietnam raged on and the civil rights progress of the previous decade had ground to a halt, Jackie Robinson no longer felt optimistic about the state of the country. For Jackie, this represented a profound shift from the patriotic rhetoric of his past. For many years, Robinson had believed that the highest ideals of American democracy could bring about the changes the Civil Rights Movement demanded. Even as other leaders made their cynicism toward American racism and injustice clear; Robinson had maintained his stance. By the late 1960s, after the assassinations of movement leaders Dr. Martin Luther King and Medgar Evers, that stance changed.

Throughout the letter, Robinson lamented how hard it was to tell these difficult truths to Jeff, but he recognized how important it is to do so. Over the course of Robinson’s life, youth empowerment was key to both his beliefs and actions. In the forties and fifties, he understood the profound impact that his baseball career could have on both Black and white children who saw him play. After his playing career was over, he made a phone call to the Little Rock Nine to show his support and led the Youth March on Washington for Integrated Schools. At his home in Stamford, Connecticut, he and Rachel would make sure to include their own children in the dinner-table conversations about their personal obligations to the Civil Rights Movement. To him, it was important that children and young adults be taken seriously, and that their opinions and ideas were treated with respect.

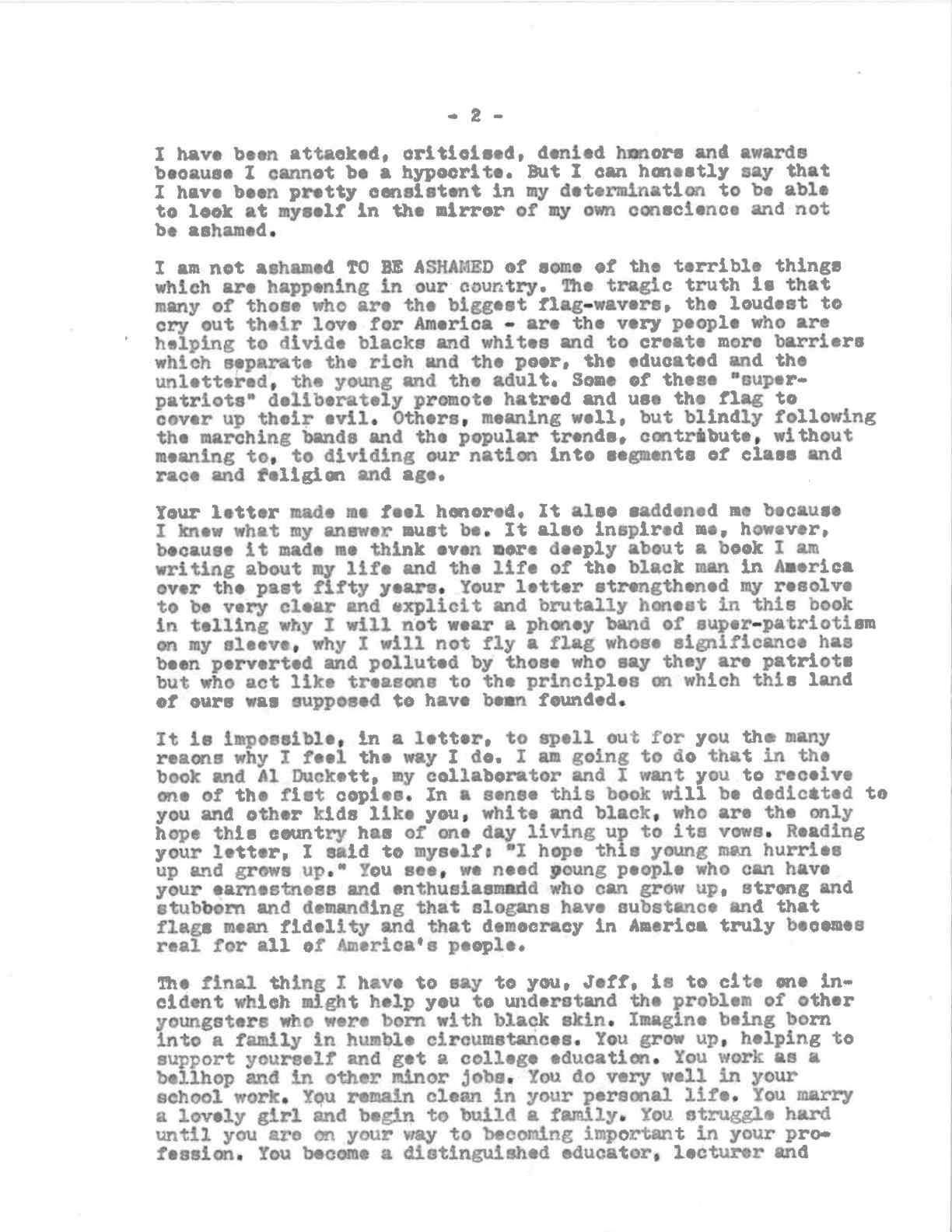

Page 2 of Robinson’s response to Jeff Auxier, March 21, 1971. Jackie Robinson Museum Collection

Later in the letter, Robinson noted that many of the things he wrote here would be reiterated in his upcoming autobiography, I Never Had It Made. The book, he said to Auxier, “will be dedicated to you and other kids like you, white and black, who are the only hope this country has of one day living up to its vows.” Jackie Robinson might have given up on empty symbols of nationalism, but he was not going to give up on the children who looked to him for encouragement and guidance. Even when the message he knew he had to deliver is not a hopeful one, he understood that his role as an elder was to provide inspiration to future generations.

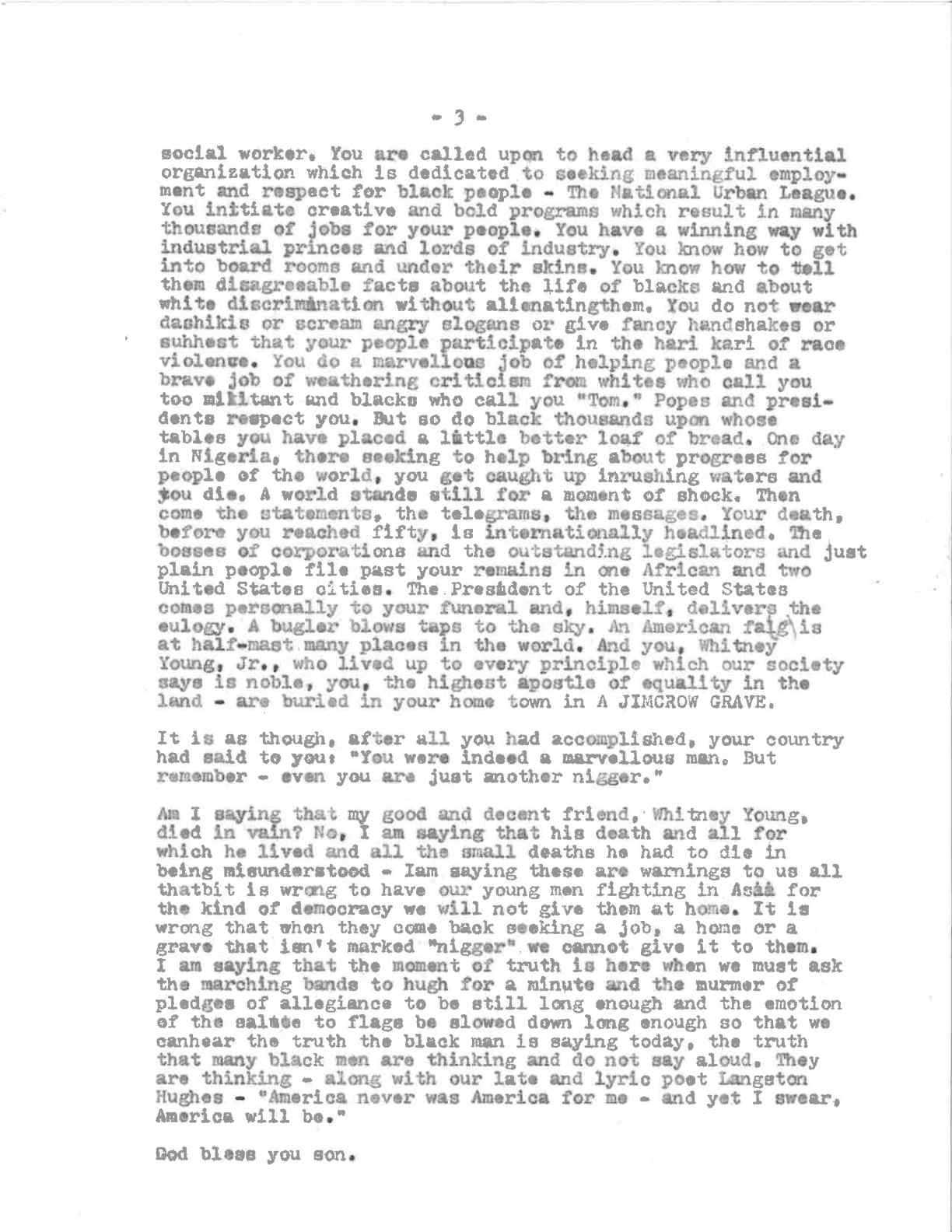

Page 3 of Robinson’s response to Jeff Auxier, March 21, 1971. Jackie Robinson Museum Collection

Header image:

Jackie Robinson speaking to students at Joan of Arc Junior High School, January 9, 1962. Bettmann Archive, Getty Images

News

Robinson accomplished a great deal on the field, but a museum celebrating his life puts as much focus on his civil rights work.

READ MORE

News

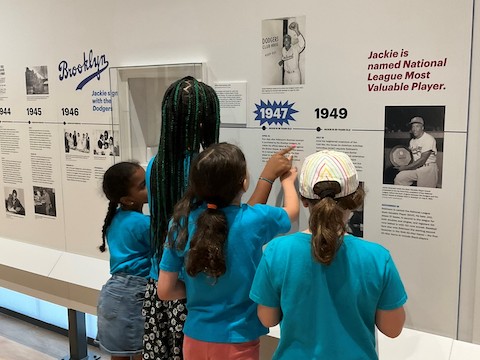

Visitors will also get to explore an immersive experience “to better understand the racism and prejudice Robinson encountered beyond the baseball field, as well as stories of his lasting influence on sports, politics and entertainment today.”

READ MORE

Programs & Events

Get the scoop on new programs and resources for teachers, students, and families!

READ MORE