News

The Jackie Robinson Museum Is About a Lot More Than Baseball

Robinson accomplished a great deal on the field, but a museum celebrating his life puts as much focus on his civil rights work.

READ MOREOn June 16, 1964, Jackie Robinson visited St. Augustine, Florida at the urging of Martin Luther King Jr.’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). A crowd of 600 had gathered at St. Paul’s A.M.E. Church that evening to hear him deliver a speech that kicked off a month-long direct-action campaign targeting the city’s segregationist policies at local businesses, beaches, and swimming pools. He blasted his critics, especially those in the white press who admonished Black superstars for joining the movement. He told stories of how Willie Mays could not buy a home in San Francisco and how Nat King Cole was beaten in Birmingham for trying to perform in front of an integrated audience. “There is not one Negro, not one that I know of in this country, that has it made,” he declared, “until the most underprivileged Negro in St. Augustine, Florida has it made!” The crowd burst into applause.

Jackie Robinson Speaks at St. Paul's A.M.E. Church in St. Augustine, Florida. Courtesy of ABC News

Robinson understood that the sleepy tourist town of St. Augustine was of critical importance to national politics. Local leaders in St. Augustine had spearheaded a massive voter registration drive the year before, and with the November election looming, Robinson was keen on delivering those votes to the candidate that would provide the firmest support to future civil rights legislation, Democratic president Lyndon Johnson, in the upcoming November election.

The 1964 Civil Rights Act was also working its way through Congress and St. Augustine was to host a celebration of the 400th anniversary of its founding a year later. With the spotlight already on the city, SCLC organizers and NAACP advisor Dr. Robert Hayling, the first African-American dentist to be elected to the local and national posts of the American Dental Association, were eager to use the media attention garnered by the upcoming celebration to their advantage as they led a month of rallies and marches. Robinson praised the protestors in his speech that evening, “You have taught me and I’m sure many people up north the kinds of accomplishments that can be made with the determination such as you have exhibited. I think the fact that people like this are willing to give up their freedom to go to jail is an indication exactly what they believe about America.”

The SCLC’s gambit worked: tourism in the summer of 1964 collapsed, forcing the hand of a remarkably conservative business community to endorse the creation of a biracial commission to combat racism in the city. The bravery of the marchers in Saint Augustine, combined with the national spotlight on the events unfolding there, helped keep civil rights at the forefront of American minds. The Civil Rights Act was signed into law less than three weeks later, banning segregation in public places.

While the protests in St. Augustine may have been a success in terms of publicizing civil rights pressure when it was most politically valuable, the on-the-ground results of the marches within the city itself were much less tangible. Businesses reluctantly integrated but found few Black customers after the sheer vitriol with which they had been previously refused. Establishments that were more public or reconciliatory about integration were met with pickets by an invigorated Ku Klux Klan. After Jackie and the SCLC left, local organizers felt abandoned by the national organization.

St. Augustine would not be Robinson’s last stop. His activism took him across the country where he spoke in churches, in auditoriums, and at protests. Just weeks after this speech, he wrote in his syndicated newspaper column “One wonders how we will ever be able to enforce the new Civil Rights Act when, so often, the fate of accused culprits is left in the hands of friends and neighbors who would rather uphold the doctrine of white supremacy than to discharge the demands of justice.” But Robinson remained undeterred, continuing to point to successful actions like St. Augustine and using his celebrity to bring the eyes of the world onto the Civil Rights Movement.

Civil Rights Library of St. Augustine, https://civilrights.flagler.edu/.

“Jackie Robinson Urges Action,” Daytona Beach News Journal, June 16, 1964

Taylor Branch, Pillar of Fire: America in the King Years, 1963-65. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster, 1998

David R. Colburn, Racial Change and Community Crisis: St. Augustine, Florida, 1877-1980. New York: Columbia University Press, 1985

Robert W. Hartley, “A Long, Hot Summer: The St. Augustine Racial Disorders of 1964,” in St. Augustine, Florida, 1963-1964: Mass Protest and Racial Violence

News

Robinson accomplished a great deal on the field, but a museum celebrating his life puts as much focus on his civil rights work.

READ MORE

News

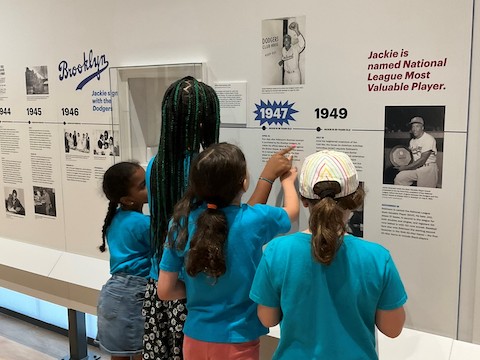

Visitors will also get to explore an immersive experience “to better understand the racism and prejudice Robinson encountered beyond the baseball field, as well as stories of his lasting influence on sports, politics and entertainment today.”

READ MORE

Programs & Events

Get the scoop on new programs and resources for teachers, students, and families!

READ MORE