News

The Jackie Robinson Museum Is About a Lot More Than Baseball

Robinson accomplished a great deal on the field, but a museum celebrating his life puts as much focus on his civil rights work.

READ MOREPlan your visit or become a member today! Admission is free over Presidents’ Day Weekend (Feb 13-15) – Reserve your spot!

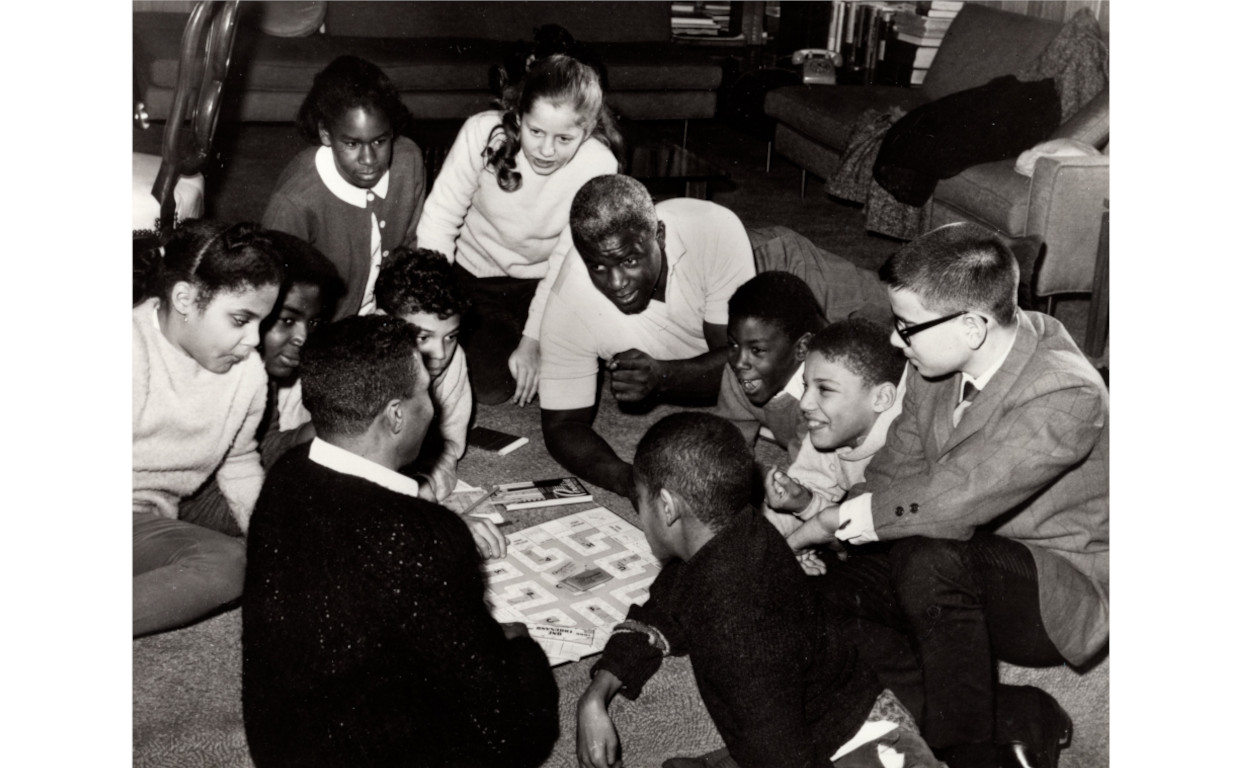

At the end of 1954, Jackie and Rachel Robinson, along with their three children, left their home in St. Albans, Queens for a new property in Stamford, Connecticut, a suburb located about an hour north of New York City. For Jackie Jr., age 7; Sharon, age 4; and David, age 2, this was a major transition. In Stamford, the Robinson kids found themselves in a wholly different environment. They were almost universally the only Black students in their classes, and the task of desegregation weighed heavily on their young shoulders. As the changes brought on by the Civil Rights Movement unfolded across the United States, the Robinsons began to understand that their stories, too, were microcosms of a broader national transformation.

Jackie Robinson playing a board game with Jackie Jr., David, Sharon, and their neighbors in Stamford, CT, date unknown. Jackie Robinson Museum

Jackie Jr. began school at Martha Hoyt Elementary soon after the move. The Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court decision, making segregation in schools illegal, had been handed down earlier that year in May 1954. Though Stamford schools were not legally segregated to begin with, the exclusivity of the community rendered Hoyt an all-white environment. As Rachel and Jackie Jr. walked towards the doors of the school on the first day, other parents whispered and stared at the unexpected sight of a Black student enrolling. Despite this response, Rachel remembered being mostly welcomed and supported in the early days of her move.1

Inside the school, the difficulties were more apparent. Writing in her memoir years later, Sharon recounted how Jackie was ignored academically, even from an early age, by most of his teachers.2 This neglect had an effect on his sense of self-worth, too. At one point, ashamed of his ancestry, Jackie began to refer to himself as Puerto Rican to his classmates.3 Being placed into such an environment at an early age made it difficult to cultivate the same type of racial pride that their father used to stand up the abuse and insults he received in baseball years earlier. In response, Rachel said, the Robinsons began to purchase books with multiracial themes to help build the kids’ confidence in their own identities in a desegregating environment.

David Robinson (second row, fourth from left) with his graduating class at New Caanan Country Day School, date unknown. David primarily attended local private schools in the Northeast, first in Connecticut and then in Massachusetts. Reflecting on his experiences, David remarked on how an overt moment of racial harassment helped galvanize the support of his closest friends during his time in school. Jackie Robinson Museum

The school system itself was not the only difficulty. In addition, the children faced racist mistreatment from their peers. These issues compounded as they grew older and formed friendships across racial lines, which were often fraught. “It became difficult when we became teenagers,” Sharon later recounted in a Jackie Robinson Museum interview.4 “Black and white kids…didn’t socialize together. There was a natural breaking-off point when you entered your teenage years.” Sharon remembered how at the time, she resented her parents for raising them in what was essentially an all-white community.5

Notably, Jackie and Rachel did not view themselves or their children as crusaders in the fight for equality. They did not move to Connecticut to stir up trouble about housing discrimination, as was alleged in the press.6 Nor did they believe that raising their children in Connecticut was purely a character-building experience. They faced the same choices that many middle-class Black families faced at the dawn of desegregation: whether to move their children and subject them to mistreatment at a better-resourced school in a wealthier, whiter community, or stay put and experience the structural racism of underinvestment in a school that was almost entirely Black.

Jackie, Rachel, and the family around their dinner table, ca. 1957. Jackie Robinson Museum

Home became a place for discussions about integration that were often just as personal as they were political. It was around the table where Jackie told his children about his calls with civil rights leaders and organizers, including the Little Rock Nine, a group of Black high school students who fought to desegregate Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas in 1957. Orville Faubus, then the governor of Arkansas, mobilized the National Guard for a days-long standoff as he fought to prevent the desegregation of Little Rock’s schools. Like millions of Americans, the Robinson kids watched the crisis unfold on television, as hundreds of white protestors gathered to prevent the students from enrolling. No state troopers blocked the doors of the Robinsons’ elementary schools, and the tree-lined streets of suburban Connecticut were a long way both literally and figuratively from the battle lines of Arkansas. Even so, their experiences revealed the importance of school desegregation to the fight for racial equality in America.

Pro-segregation protestors gather outside the State Capitol in Little Rock, Arkansas, 1959. Two years earlier, nine Black students attempting to enroll at Central High School were greeted by a similar mob. Wikimedia Commons.

As Jackie Jr., Sharon, and David grew older, the fight for desegregation in education continued, and the three children were looking for a way to add their voices to the growing chorus. In 1963, the Robinson family traveled south to participate in the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. After years of discussing the unfolding movement at home, the three Robinson children were able to join in, clapping and singing as hundreds of thousands of marchers gathered to fight for equality and listen to the words of the architects of the movement. Writing in his weekly column in the New York Amsterdam News, Jackie focused on the experiences of his children, describing Jackie Jr.’s excitement for the movement and David’s brief interview with a reporter.7 To Jackie, this march was an opportunity to share his civil rights work with the children who, up to that point, had only experienced it through the television and through their father’s stories.

David, Jackie, and Daisy Bates march together at the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom in 1963. Getty Images

After the march, the Robinsons returned to Stamford invigorated and with a sustained sense of purpose. Over the years, their home became a place for civil rights jazz fundraisers, meetings with prominent politicians, and gatherings with friends new and old. But the difficult memories of integration were not lessened by developments. Later on, Jackie wrote candidly about the issues his children faced. “We now realize how much being the only black can hurt,” he noted, reflecting on the weight of their struggles.8 “A good school involves much more than excellent teaching.” Even in the face of these challenges, the Robinsons were able to learn and grow amidst the tumult of change. The stories shared around the table and the joy of the marches offered the chance for the Robinson children to see that they were not alone in a changing America. More than anything else, they revealed how the nationwide struggle for desegregation was most acutely felt by the children who carried the burdens of being the “first,” just like Jackie himself.

News

Robinson accomplished a great deal on the field, but a museum celebrating his life puts as much focus on his civil rights work.

READ MORE

News

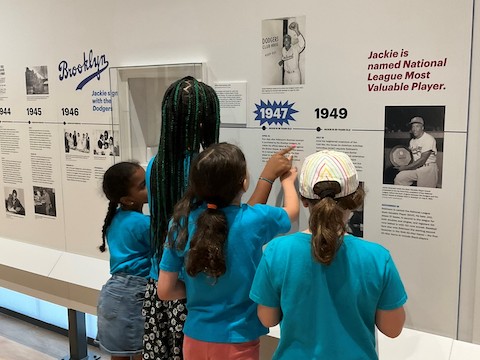

Visitors will also get to explore an immersive experience “to better understand the racism and prejudice Robinson encountered beyond the baseball field, as well as stories of his lasting influence on sports, politics and entertainment today.”

READ MORE

Programs & Events

Get the scoop on new programs and resources for teachers, students, and families!

READ MORE