News

The Jackie Robinson Museum Is About a Lot More Than Baseball

Robinson accomplished a great deal on the field, but a museum celebrating his life puts as much focus on his civil rights work.

READ MOREPlan your visit or become a member today! Admission is free over Presidents’ Day Weekend (Feb 13-15) – Reserve your spot!

Perhaps no other day lives on in Brooklyn Dodger infamy as does the afternoon of October 3, 1951. What was once a thirteen-game lead over the New York Giants, the Bums’ hated crosstown rival, disappeared in a flash as the Giants’ Bobby Thomson hooked a walk-off home run over the Polo Grounds’ left-field fence. For Jackie Robinson, his Dodgers, and the thousands of Brooklynites who lived and died with the team, the loss was the latest insult in a long line of crushing defeats and missed chances dating back over decades of play. Ralph Branca, the unfortunate Dodger hurler who surrendered the homer, would be haunted for the rest of his life by one at bat. Though the “Shot Heard ‘Round the World,” as it came to be known, was a landmark moment in Dodger history, two of its key participants, Branca and Robinson, shared a friendship that could not be defined a single, heartbreaking home run.

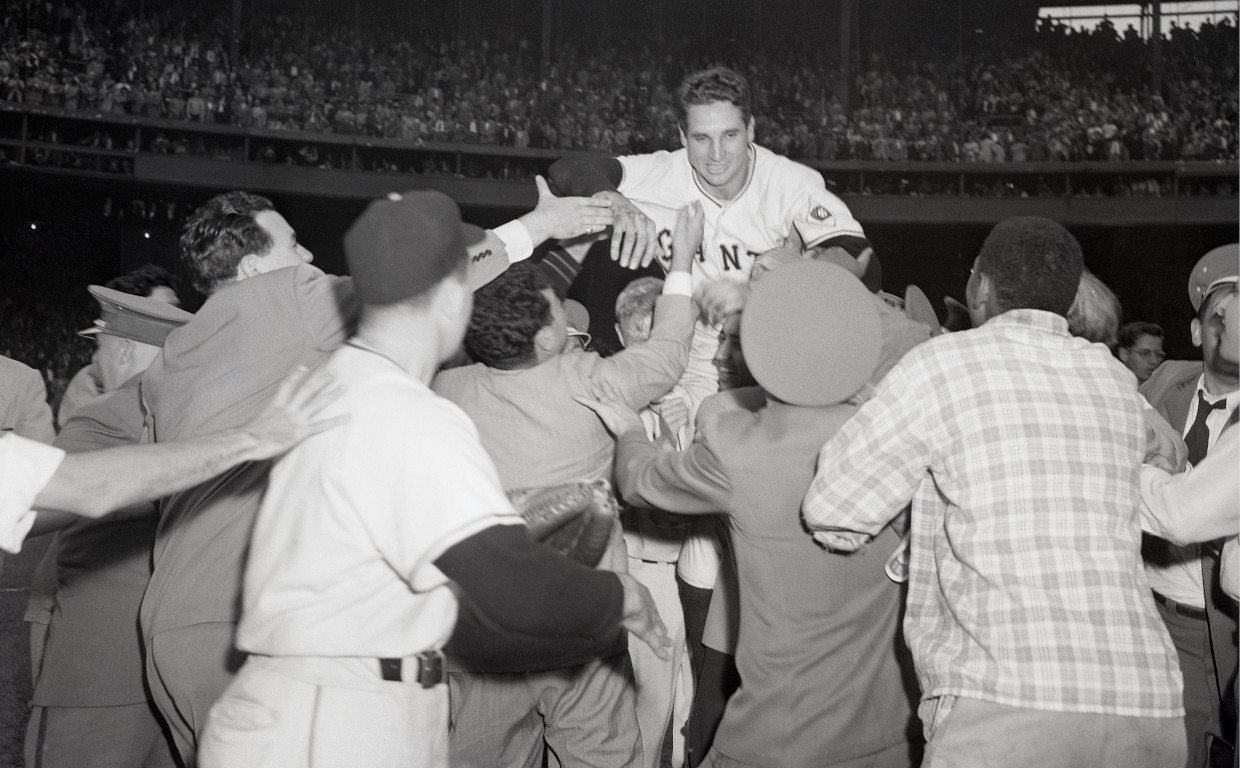

Bobby Thomson is carried off the field by adoring fans after his home run sent the New York Giants to the 1951 World Series. Getty Images

Prior to the modern era of convoluted playoff brackets and Wild Card showdowns, the World Series was played between the winners of the American and National Leagues. It was as simple as that. Find yourself at the top of your league at the end of September and you’ll punch your ticket to the Fall Classic. If there was a tie, there would be a three-game playoff to determine the winner. For most of the 1951 season, the Brooklyn Dodgers looked like the sure victors. After taking the lead in the National League in the middle of May, it was hard to deny that they were the team to beat. Beginning in August, however, the Giants began to surge. After a sixteen-game winning streak and stellar play down the stretch, they found themselves in a tie with the Dodgers before the final game of the season.

(left to right) Duke Snider, Gil Hodges, Jackie Robinson, Pee Wee Reese, and Roy Campanella pose together in June 1951. This season, Jackie’s fifth, was a banner year for the Dodgers offense. Robinson himself had his best year, and Campanella won his first of three Most Valuable Player awards. Getty Images

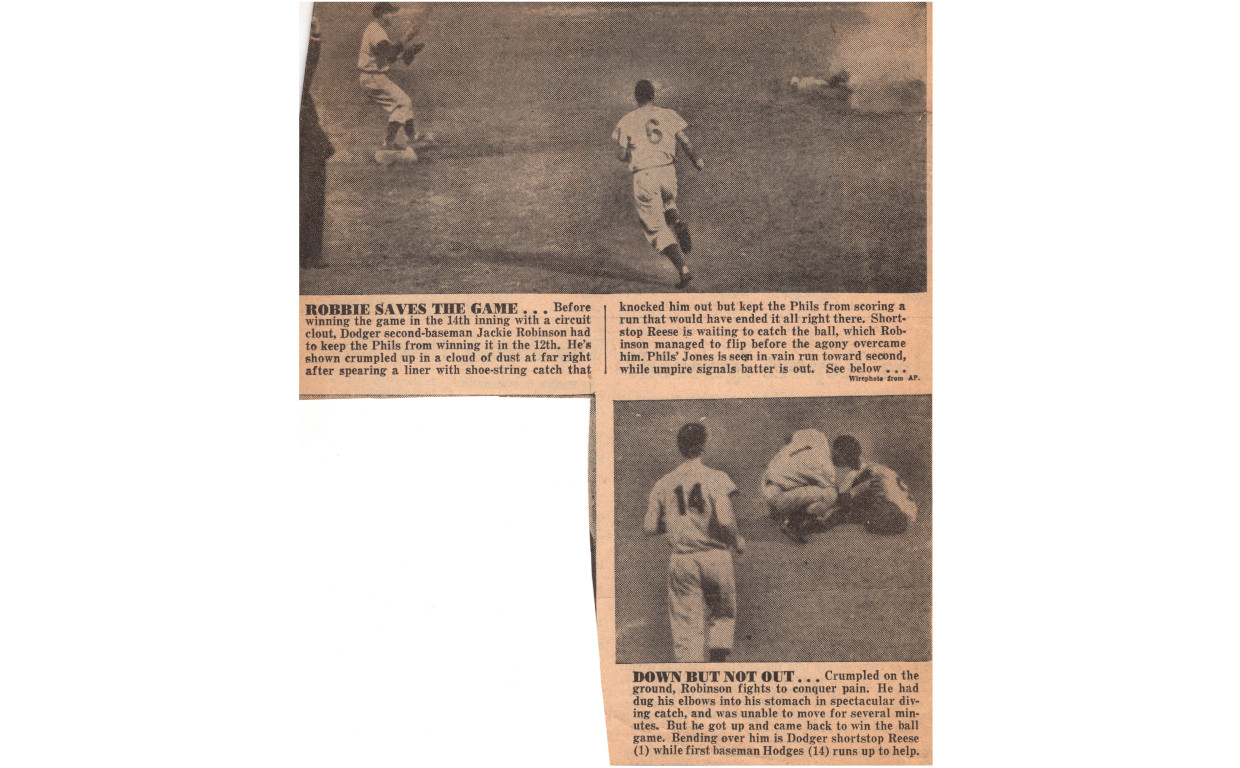

If it had not been for Jackie Robinson’s heroics, the Dodgers’ season would have ended then and there. After the Giants defeated Boston in quick fashion, Brooklyn needed a win over Philadelphia to even force a playoff. The game began disastrously. The Dodgers found themselves down 6 to 1 at the end of three innings but were able to tie the game at eight apiece at the end of nine. With the bases loaded at the bottom of the twelfth, the Phillies’ Eddie Waitkus smashed a liner up the middle that was sure to be a walk-off hit. Miraculously, Robinson, ranging from his position at second, leaped to grab the ball, nearly knocking himself out cold as he slammed into the hard dirt of Shibe Park. “I flipped the ball away so everyone would know I had caught it,” Robinson said, a prudent move, given that the catch could have been disputed.1 After he lay on the ground for five minutes, manager Charlie Dressen and the Dodgers trainer were able to help him off the field. In the top of the fourteenth, Robinson, having been revived with a piece of ammonia-soaked cotton, returned to the batter’s box and hit a homer into the left field stands.2 Speaking to the Herald Tribune after the game, Robinson declared it the greatest home run he ever hit.3 For a moment, the Bums’ pennant hopes were saved.

In this pair of Associated Press wirephotos, Robinson can be seen lying in a cloud of dust after his season-saving catch in the bottom of the twelfth inning against the Phillies. Newspaper unknown, Jackie Robinson Museum Collection

The playoff with the Giants began the next day. For Brooklyn fans, there was plenty of reason to be worried. The pitching staff was tired, and the momentum was obviously with New York. The first two games, split between Ebbets Field and the Giants’ Polo Grounds, were less than eventful. The Giants won the first game 3 to 1, with Ralph Branca himself earning the loss. Clem Labine, who had proven effective for the Dodgers down the stretch, pitched a 10–0 shutout in the second. The stage was set for a winner-take-all showdown in Manhattan, with the victor going on to face the fearsome New York Yankees in the World Series.

The final game started on a positive note for Brooklyn. With Pee Wee Reese at second base in the top of the first inning, Jackie Robinson singled to left, giving the Dodgers their first lead of the afternoon. For the next seven innings, pitchers reigned. Don Newcombe, who had pitched five innings of the marathon against Philadelphia just three days earlier, cruised through the first eight innings, giving up only a single run. A three spot in the top of the eighth for Brooklyn, including an intentional walk for Robinson, put the Dodgers up 4 to 1.

What followed was one of the most fateful managerial decisions in baseball history, one that has been endlessly debated by fans to this day. The Giants’ Bobby Thomson was coming to the plate, representing the winning run. When Dodgers manager Charlie Dressen strode to the mound to replace Newcombe, he was faced with a choice: would he bring in Carl Erskine, who had pitched effectively that season but was troubled with nagging arm problems, or would he turn to Ralph Branca, who had pitched two days prior in the Dodgers’ first loss? Dressen chose Branca, and the rest is history. On the second pitch of the at-bat, Thomson whacked a fastball over the Polo Grounds’ short left-field porch, sending the fans into delirium and the Giants to the World Series for the first time since the Great Depression.4

Click to watch the Shot Heard ‘Round the World, courtesy of MLB

In hindsight, the decision to go with Branca was itself questionable. Though the Dodgers were the first team to employ a statistician, Dressen was likely unaware that Thomson had hit Branca effectively throughout the entire season. Unrelated to Branca, of course, was the fact that the Giants also had an elaborate electronic mechanism for surreptitiously stealing opposing catchers’ signs from center field, though it remains unclear whether or not Thomson knew what pitch was coming, or if that information was of use to him.5

Newcombe, by this point, was tiring, and it began to show in the bottom of the ninth. The first two Giants, Alvin Dark and Don Mueller, reached on singles. After inducing a popout from former Negro Leagues great Monte Irvin, Whitey Lockman doubled to left, and Newcombe’s night was over.

Thomson’s home run was likely aided by the highly unusual dimensions of the Polo Grounds, on display in this 1923 photo. The distance from home plate to the left field foul pole was only 279 feet, meaning that the Shot Heard ‘Round the World might have only been heard in left fielder Andy Pafko’s glove had the game been played at Brooklyn’s Ebbets field…or any modern-day ballpark!

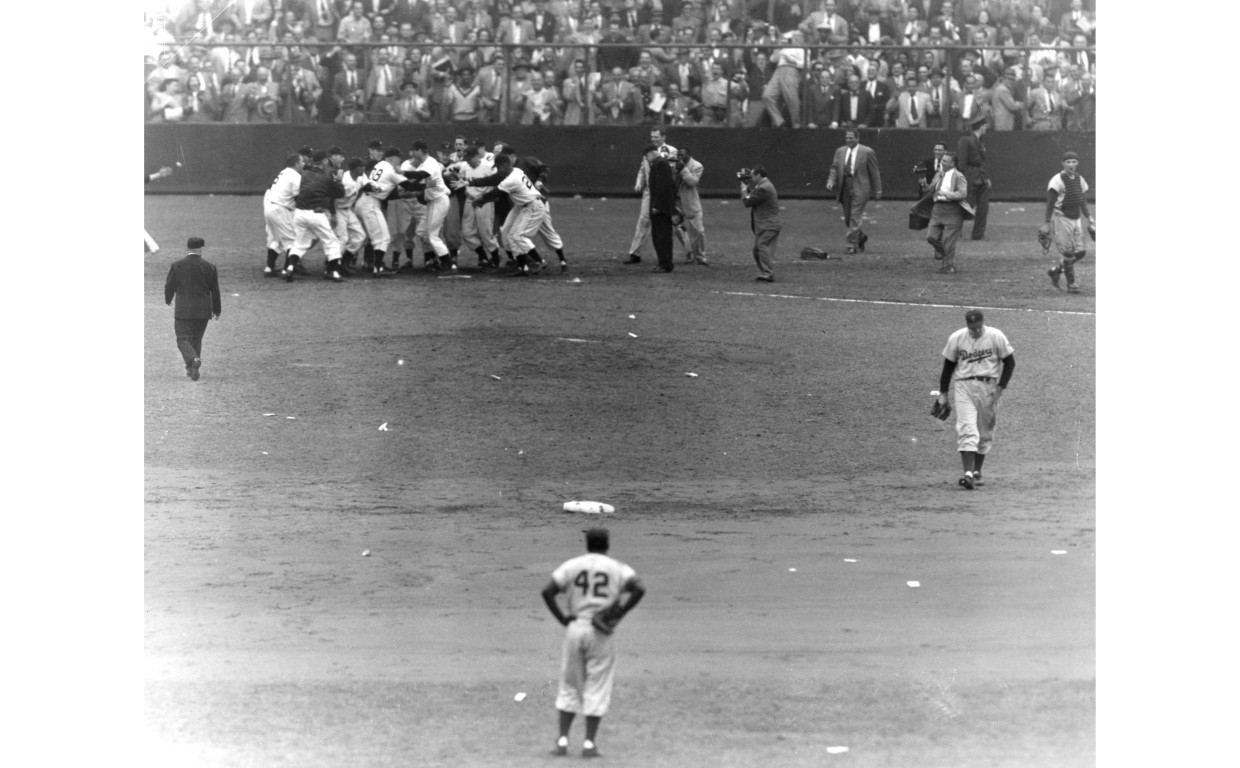

Robinson watched the entire play from his position at second base. While most of his teammates began to leave the field as soon as the ball left the field of play, Robinson stayed behind, creating one of the most striking images in baseball history. Already known as one of baseball’s most fearsome competitors, Robinson stood with his hands on his hips, eyes down, as he made sure Thomson touched every base. Only when the Giants began their celebration around home plate did he finally leave his post.

Jackie Robinson stands with his hands on his hips as Bobby Thomson’s teammates gather around home plate. At right, Ralph Branca walks dejectedly from the mound. Getty Images

For all the broken hearts from Gowanus to Bed-Stuy, none were as shattered as that of Ralph Branca. When he returned to the dugout, almost none of his teammates came to console him. For a brief moment, Branca was alone in defeat. “Hardly anyone knows what happened afterward,” Branca later remarked.6 “I’m sitting there by my locker with my head down and Jackie comes over to me and taps me on the shoulder and says: ’Don’t hang your head. If it wasn’t for you we wouldn’t even have been here’…[W]hat made it significant was the fact that Jackie was the only player to come over and talk to me after that game. He was not just a teammate. He was my best friend on that team.”

Ralph Branca and Jackie Robinson vigorously shake hands after inking their 1948 contracts with the Brooklyn Dodgers. Associated Press

Robinson took this role seriously. When he joined the Dodgers in 1947, he was often described as the loneliest man in baseball. Few of his teammates spoke to him, and he was seldom included in the card games and shared meals that defined the culture of ball players on the road. Ralph Branca was one of Robinson’s first real allies on the team. He was the only Dodger to stand beside Robinson on Opening Day, and he slowly brought Robinson into the social life of the team. Soon, Jackie began to confide in Branca during the difficult period in 1947, when opponents were hurling beanballs and slurs as he fought to integrate the game. When Robinson joined Branca in the locker room after the loss to the Giants four years later, it was not merely an empty gesture to console the losing pitcher after a tough outing. It was a debt repaid.

Though the Dodgers were sent home, there was still more baseball to be played in New York. The Giants would go on to lose the World Series to the Yankees in rather forgettable fashion, being defeated in six games. Soon, the Dodgers would find themselves back on top again, winning the National League pennant in 1952 and 1953. Ralph Branca, unfortunately, did not return to form. After injuring himself in spring training in 1952, he never pitched with the same effectiveness he had throughout most of the 1951 season.

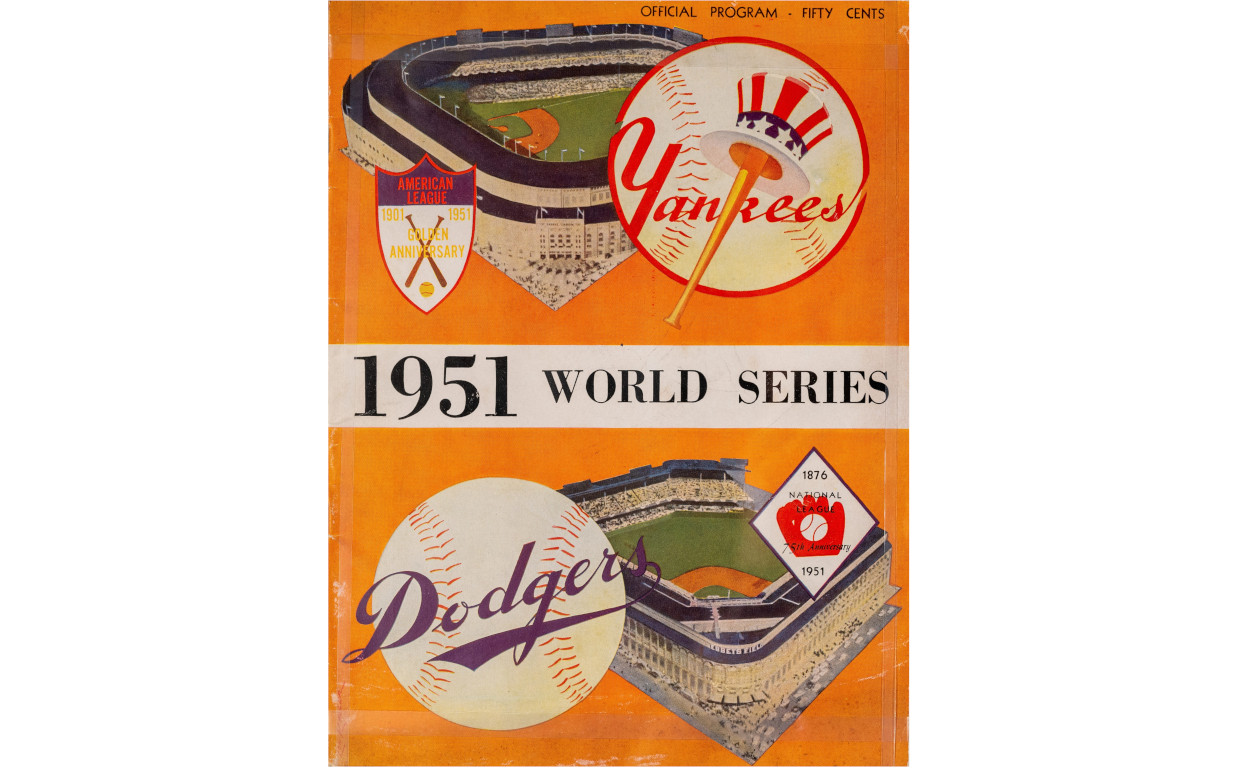

The Brooklyn Dodgers were at one point thirteen games ahead of the Giants in the quest for the pennant. This pre-printed program for a Dodgers-Yankees World Series was never used. walteromalley.com

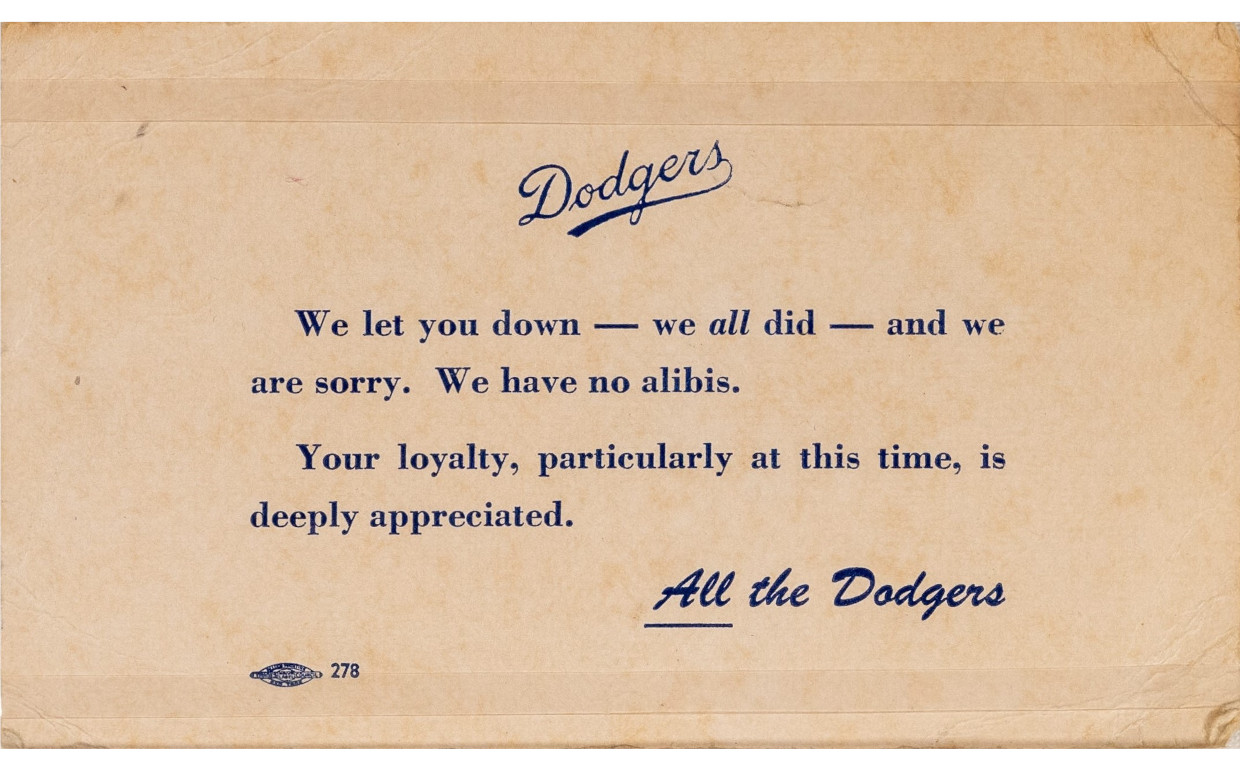

Dodgers season ticket holders were sent this unusual apology card shortly after the loss to the giants. walteromalley.com

Unsurprisingly, Branca continued to field questions about the fateful pitch for the rest of his life. When he did so, however, he often spoke candidly about the role Robinson played that afternoon in the clubhouse and the bonds that they forged over their careers. As fans continued to celebrate both Robinson and the Dodgers in the decades after the team left for Los Angeles, Branca focused on the importance of being a good teammate even under the most trying conditions. The Shot Heard ‘Round the World is a story of heartbreak still wistfully recalled by a generation of fans who remember the golden age of New York baseball. But for its participants, it was a moment of solidarity and friendship that Branca preserved and passed down through generations alongside the story of the Dodgers’ crushing defeat.

News

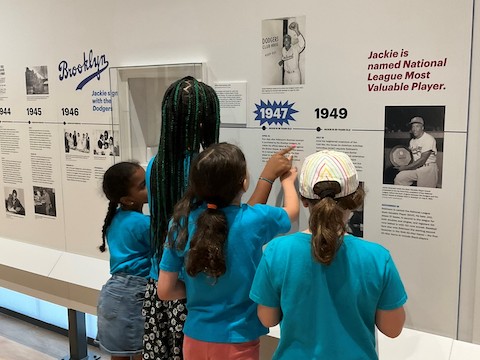

Robinson accomplished a great deal on the field, but a museum celebrating his life puts as much focus on his civil rights work.

READ MORE

News

Visitors will also get to explore an immersive experience “to better understand the racism and prejudice Robinson encountered beyond the baseball field, as well as stories of his lasting influence on sports, politics and entertainment today.”

READ MORE

Programs & Events

Get the scoop on new programs and resources for teachers, students, and families!

READ MORE